In defence of Liam Stacey’s freedom of speech Comment

Features, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Saturday, April 7, 2012 0:00 - 5 Comments

By Musab Younis

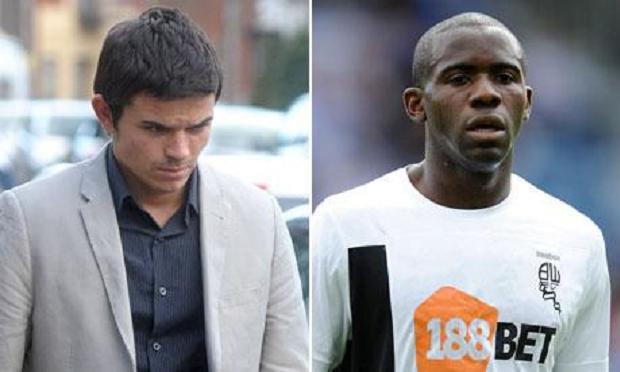

Liam Stacey (Left) who was jailed in March 2012 for racist tweets about Bolton footballer Fabrice Muamba

Last week, the Welsh university student Liam Stacey was jailed for 56 days after complaints were lodged over a number of offensive messages he had posted on Twitter, first about the footballer Fabrice Muamba, then about his fellow Twitter users. He pleaded guilty to a racially aggravated offence under Section 4A of the Public order Act 1986.

Stacey’s arrest and imprisonment have been met with collective approval, barring a couple of exceptions. A sample of comments from an internet message board: “Let him learn his lesson for being a thoroughly nasty individual.” “I take a libertarian view of freedom of expression, but even then there have to be limits, and this is an instance of speech that should NOT be protected by the freedom of expression.” “I’m sorry but this has nothing to do with freedom.”

Stacey’s case is not the first of its type, though it seems to be a first for Twitter. In 2006, Mizanur Rahman, 23, was convicted of inciting racial hatred for calling on God to bring death to various nationalities at a protest in London. On retrial, he was additionally convicted on the charge of solicitation to murder and sentenced to six years in prison (later reduced to four). He had, ironically, been protesting against the publication of the Danish cartoons that had insulted the Prophet. In 2010, two neo-Nazis were jailed for between two and two-and-a-half years for posting racist messages online. The judge told one of them: “You are a lonely man with little in your life.” Just two weeks ago, a young man named Azhar Ahmed who wrote on Facebook that British soldiers were going to hell for killing Afghans was arrested. He was initially charged with a “racially aggravated public order offence”, but after this was withdrawn – the minor problem being that his comments did not actually mention race – he is being charged instead, under the Communications Act 2003, with “sending a message that was grossly offensive.”

The near-universal public acceptance of most of these charges and convictions presents a troubling consensus: that certain types of speech should be regulated by the state. The process by which public acceptance of such restrictions is secured is a familiar one. First, the state is anointed the arbiter of speech. Some speech is then decreed “beyond the pale” and “going too far” (at which point, watch out for clichés.) Someone is designated as being an insalubrious individual. Their subsequent imprisonment is applauded, or even seen as too lenient.

Voltaire’s elementary principle, that the right to freedom of speech should be defended precisely for those instances of speech that one detests, is known widely enough but seems, in practice, to be absent from public discourse. One searches in vain for those willing to defend the right to free expression of both Salman Rushdie and Omar Bakri. All that is currently required is the ability to paint someone as a fool or a bigot, and suddenly any manner of punishment is accepted to be their due. (The countless comments on Liam Stacey’s character are a testament to this.) This mode of thinking saturates a criminal justice system that already feeds on class distinctions, where a busy haze of signifiers surrounds individuals and condemns them: first to public distaste, then to prison.

Three points need to be considered by anti-racism organisers. The first is that, while the legislation on racial hatred may appear to be on their side, its implementation is (unsurprisingly) racialised: the probabilities of being charged, and receiving a longer sentence, appear higher for members of the very communities that are supposed to be protected. For example, the cases that Blackstone’s Criminal Practice 2012 give of ‘solicitation to murder’ charges mostly involve men trying to pay someone to kill their wives. It does not seem immediately evident why calling upon God to destroy a particular nationality fits within the same category, but doubtless the prosecutors in the case mentioned above were helped by the fact that the men being tried were Muslim. (Blackstone’s provide other examples of the loosening of this law. The cases have names like Abu Hamza and El-Faisal.) The same can be applied to the case of Azhar Ahmed. Others who have been subject to wide interpretation of hazily-formulated terror charges relating to “propaganda materials”, like Samina Malik, have endured the same experience.

Secondly, racism has not been and will not be eliminated by laws restricting the expression of racial hatred. Not only does racism continue to seep into speech and action, and into the minds of the police and job interviewers, but it remains – as anti-racism organisers know – part of a structure of oppression and domination that is not limited to crude words or cheap shots. To make much of the laws on racial hatred is to buy into a discourse that paints racism as a product of individual perceptions and prejudices, rather than as the observable outcome of a system that multifariously racialises groups of people the better to subjugate and dehumanise them.

The third point is that, under the current laws on incitement, major civil rights figures like Malcolm X would have faced periods of imprisonment. It is not difficult to find speeches from the civil rights era which can easily be interpreted as the incitement of hatred against white people. If one supports the application of laws on incitememt, one would have to accept that Nation of Islam members would have deserved prison for their statements just as Stacey deserved prison for his. To be realistic would be to accept that African-American radicals would in fact have been the primary targets of any laws on incitement to racial hatred, in a situation where the US government was resorting to a plethora of illegal and subversive tactics in an attempt to destroy the civil and economic rights movement.

It is unfortunate that those who demand freedom of speech tend to be hypocrites: that is, they defend it when it suits them, but are silent when its contravention is to their advantage. This can be applied to cynical right-wing commentators like Philip Johnston, who raged against the Home Office ban on Geert Wilders but has not uttered a word about Azhar Ahmed, but also to those who have defended Ahmed but have attempted to stop Nick Griffin from speaking. It applies similarly, in my view, to those who accept freedom of expression “except for fascists” or some other commonly-applied epithet – “terrorists”, “extremists”, “those who would restrict the free expression of others”.

This latter category is a particularly curious one because it states that, if you are in favour of some restrictions on freedom of expression, you do not yourself deserve the right to freedom of expression. One can imagine the vast swathes of people who would have to be banned from speaking were this rule to be applied universally. The central problem with banning “fascists” is that it implies there is to be central committee determining who is and who is not a fascist. How such committees have operated before is a matter of historical record and always worth revisiting.

Some anti-racists will argue that although they agree with me in spirit, if we were to permit in public racist language the result would be an increase in racist attacks. Such attacks, increasing in many parts of Europe and fuelled by a worryingly chauvinistic public discourse, should be taken seriously. But if these are the criteria for deciding on laws, then surely they can be extended much further. A detailed report from the University of Exeter found “prima facie and empirical evidence to demonstrate that assailants of Muslims are invariably motivated by a negative view of Muslims” often acquired from the “mainstream media”. Should national newspapers and broadcasters therefore be banned from reporting stories about Muslims? If I can prove that wearing the niqab leads to an increase in racist attacks, should we ban the niqab?

Such a consequentialist outlook has obvious flaws: it mirrors, in an odd sense, the right-wing argument that immigration itself causes racism. It does so because it absolves the actual perpetrators of crimes and projects their actions elsewhere. It is precisely this argument that led Geraldo Rivera on Fox News to state, with regard to the murdered black Florida teenager Trayvon Martin, that “the hoodie is as much responsible for Trayvon Martin’s death as much as George Zimmerman was.” If we deplore Rivera’s argument, we should deplore its counterpart. In the unlikely event that someone had been inspired by Stacey’s tweets to attack someone they perceived to be non-European, that person would have been fully responsible for their own actions; Stacey’s moronic vulgarity should provide them with no excuse.

I certainly accept that a racist public discourse legitimates racist violence, and that this is a serious and worrying development that deserves attention and action. But such action is not, in my opinion, legislation on speech. It must involve methods of community and anti-racism organising of the type that many thousands of individuals have been involved in for many years. We might want to bear in mind that despite the Race Relations Act, we have a racist public discourse: witness the most recent performance by the Daily Mail in its attack on Trayvon Martin. In France, where restrictions on freedom of speech are more stringent than in England, racism is yet more entrenched. On the other hand, the much more limited restrictions on free speech in the United States are not the main target of anti-racism groups – few seem to think that a ban on words will heal America’s deeply racist criminal justice system, and for good reasons.

Should there be any limits at all on freedom of expression? Yes, but they should be as narrowly defined as possible. In the US the limits are drawn at “fighting words” – i.e. direct incitement. For John Stuart Mill:

even opinions lose their immunity, when the circumstances in which they are expressed are such as to constitute their expression a positive instigation to some mischievous act. An opinion that corn-dealers are starvers of the poor … ought to be unmolested when simply circulated through the press, but may justly incur punishment when delivered orally to an excited mob assembled before the house of a corn-dealer.

The current American system is a loose approximation of Mill’s argument (of course, with various flaws) and I think it is broadly the only tenable position. If I direct a mob to assault or murder someone, my speech should not be protected. But direct incitement of this type is rare. If I make statements that might cause someone to hate a particular group, and they consequently direct violence toward members of this group, my speech should be robustly challenged, but it should not land me in prison. Expression is not the same as action. As Eric Barendt notes, ‘a free speech principle means that expression should often be tolerated, even when conduct which produces comparable offence or harmful effects might properly be proscribed.’

To accept legal limitations on expression because of its possible effects on conduct is to express a level of trust in the state that does not bear historical examination. It also projects the focus of serious efforts to prevent hate crime onto the wrong plane, identifying a narrow tranche of proscription and accepting all other speech as non-problematic. What has been the result? Just as yet more evidence emerges of systematic police racism in Britain, less than a year after the police killing of a black man in Tottenham precipitated days of riots, and as migrants and refugees continue to face the inhumane conditions of detention centres, this government finds that all it takes to be showered with anti-racist credentials is to jail a student over some idiotic tweets.

[Article amended on 7/04: Stacey’s offence was under the Public Order Act, not incitement to racial hatred as originally stated.]

5 Comments

Simon

dissident

I broadly agree here. Though TBH I think Mill’s argument is also too open to abuse. There is no way that saying “corn-dealers are thieves” is any kind of actionable incitement. And even if it is, why is it any worse to incite the excluded than to incite violence by the state? A comparable case would be the August arrests for creating Facebook pages calling for unrest in various towns. There is no way that calling on people to be involved in an uprising as in August should be a crime, especially not while bigots are simultaneously inciting the police to greater and greater atrocities. All they’ve done is called on people to assemble. Compare also the abuse of “conspiracy” – especially the view that someone on a protest or in a campaign is in “conspiracy” with others who do something illegal (e.g. the Shac trial, the Canadian G20 conspiracy case, the Gandalf trial, the London antifa trial, the arrests after the Spanish general strike). Whenever I’ve seen this used, it’s been to criminalise thought-crimes or free association. We’d be safer if the state didn’t have any of these laws to abuse – any good they do is outweighed by the abuse to which they are undoubtedly put.

The “harassment” law is one of the worst on the books – it basically makes it a crime to be offensive. Its origins were fairly mundane (to criminalise stalking) but it is absurdly broad. It doesn’t distinguish whether this offensiveness is morality-dependent, and therefore, is used as a backdoor to enforce all kinds of bigotry which would never make it into law on its own merits. There’s cases where people have been jailed for trolling, which is basically a form of parody. It also makes it a crime to be psychologically different, since one could easily “alarm or distress” others without any intent whatsoever. Then on the other side, right-wingers get away with being as offensive as they like. There’s a horrible double standard in public discourse today, where calling a right-winger a fascist, calling Britain a police-state, calling the army killers or the police pigs or a judge a tyrant is taboo, yet slandering victims of police abuse, calling critics extremists or terrorists, calling protesters “thugs” or “scum” is common parlance; where condoning any “crime” however minor is taboo, yet inciting human rights violations by the state – including downright illegal ones – hanging, flogging, torture, extrajudicial execution, is a daily occurrence. Even the centre-left papers are complicit in maintaining this stilted “sphere of legitimate dissent” in which only reactionary bigots can rant with impunity. It’s impossible to have an equal discussion when one side, but not the other, is allowed to unleash itself – it’s like playing a football match on a tilted pitch.

The double standard is the real catch. I cannot see any justice in a system where it is illegal to call for judges or police to be strung from lamp-posts, but legal to call for police to shoot “rioters” or striking public sector workers. It’s obvious that laws are being applied selectively to silence dissent. When this occurs, it invalidates the entire law.

I’d say about racism that there’s a difference between actually racially abusing or threatening someone (the original intent of that law I think?) and simply expressing opinions on a web forum or a tweet. I can see the argument for banning illocutionary speech-acts which enforce racial segregation, but I can’t see how it would extend to these kinds of things. I completely agree with you that the Muamba tweet is protected speech. In fact, making these kinds of comments has long been a central part of football fan culture. Liverpool fans make fun of the Munich air disaster, Man Utd fans chant that too few people died at Hillsborough. It’s offensive, it’s carnivalesque, it’s part of the ritualised aggression which football rivalry is all about. Now people are being criminalised all over for it. I’ve heard of someone banned for life for calling an opposing player an “English bastard”, others held in police cells for singing anti-imperialist songs. It’s the mark of a police state, and it goes hand in hand with the destruction of football fan culture. And this is one facet of a broader cultural death. In general, public life is dying in Britain, only managed participation remains.

Musab

Simon- thanks for the correction on the actual charge, I’ll amend the article. On “collective approval”, I could only find two articles in the mainstream press that expressed any concern about Stacey’s imprisonment- one (very mild one) in the Guardian, one in the Mail. There was also a Telegraph blog which stated the sentence was too long and should have been suspended. I can barely find a single sentence in the mainstream press that argues Liam Stacey’s right to freedom of expression should be protected, but of course happy to be corrected on this.

Dissident- yes, completely agree, particularly on the stilted “sphere of legitimate dissent”. In my experience, the European left in general seems disinterested in defending freedom of expression. It makes any discussion on the topic saturated with hypocrisy; people only invoke the right to protected speech when the speech is something they agree with anyway– an obvious absurdity. The position you stated is the correct one, in my view: “We’d be safer if the state didn’t have any of these laws to abuse – any good they do is outweighed by the abuse to which they are undoubtedly put.”

Denis Cooper

I wondered precisely what charge had got this bloke banged up for 56 days, and found:

http://blog.cps.gov.uk/2012/03/liam-staceys-conviction-for-tweet-about-fabrice-muamba.html

“There have been some inaccurate reports in a number of places about the offence with which Liam Stacey was charged. He was charged with, and pleaded guilty to, a Racially Aggravated s4A Public order Act 1986, and not inciting racial hatred.”

If it had been inciting racial hatred, Part III of that Act:

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1986/64/contents

then the prosecution could not have gone ahead without the consent of the Attorney-General.

Section 4A, which was not in the original 1986 Act but was inserted through an 1994 Act, starts:

“A person is guilty of an offence if, with intent to cause a person harassment, alarm or distress, he – …”

Was that the intent of his tweets, “to cause a person harassment, alarm or distress”?

If so, which person or persons was he targetting?

dissident

With that charge, they don’t have to prove he “intended” to harass anyone, just that it was a likely effect. There doesn’t even have to be anyone who actually felt harassed. The same vague and extremely broad criterion applies to the issuing of ASBO’s, except in that case it can either be “likely to” or have caused harassment.

However, the case didn’t have to be made in court against Liam Stacey, because he pled guilty. There’s now a lot of pressure on people to plead guilty, even when they have defensible cases – to massively reduce the eventual sentence, to avoid classification as unremorseful, to avoid the stress of a lengthy pre-trial period, to avoid draconian bail terms (e.g. Internet bans) which may last much longer than the eventual sentence, or because, with reforms to legal aid and absurdly complicated paperwork, they’re unable to obtain a proper legal defence.

Notice that the category of harassment includes morality-dependent distress – if John thinks that wearing purple is a sin, and Fred walks around wearing purple, then in principle Fred is harassing John. Note also, however, that whether “harassment” counts as prohibited may depend whether a court thinks it’s predictable, or the harassed person is being “reasonable”. So in practice it turns out – if something causes morality-dependent distress to a person whose morality is conventional enough to be recognisable to a judge, they’re committing harassment. In other words, harassment effectively enforces conformity to mainstream morality, regardless of whether it’s otherwise legislated. It’s basically a theocratic position. And the law is vague enough that, whenever mainstream morality changes, so does the meaning of harassment.

It is also a blatant double standard. Dissidents and members of marginal groups are caused “harassment, alarm and distress” pretty much non-stop, through demonisation, witch-hunts, police persecution, practices such as stop-and-search, constant threats from the system and so on – but this is quietly defined as not counting. It’s a status issue: “we can harass you, you can’t harass us back”.

Liam Stacey was not convicted of inciting racial hatred. He was convicted under section 4A of the public order act for offensive or abusive words with intent to cause distress.

Also, there has not been collective approval. The general consensus seems to be that the sentence was ridiculous. You only have to search the internet to find articles from right across the political spectrum, from the far left to the far right, condemning this trial.

The European Commissioner for Human Rights stated that it was excessive and “wrong”.

I do agree though that the disapproval is generally much more muted when it is a Muslim.

That’s why I think speech laws are divisive. They pit one ethnic group against another.