‘He could not breathe’: Remembering Jimmy Mubenga, eight years on Comment

Editor's Desk, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, October 26, 2018 11:01 - 1 Comment

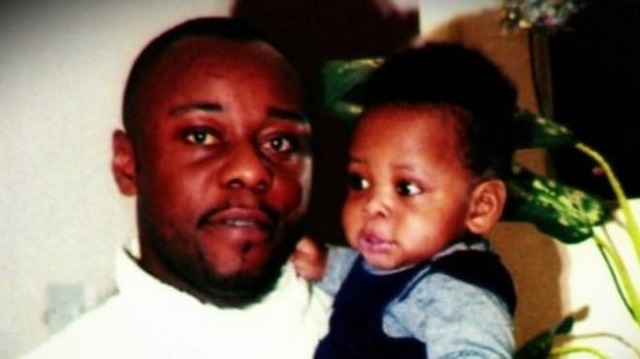

(Source: Family handout)

Eight years ago, on the evening of 12 October 2010, Jimmy Mubenga, a healthy 46 year old and father of five children, boarded a British Airways plane at Heathrow Airport. He was being deported to Angola, escorted by three guards from G4S, a security company working under contract to the UK Home Office.

The guards stood to lose £170 each if the deportation failed to go ahead. They forced Jimmy Mubenga into a seat at the rear of the plane, pulled his hands behind his back, wrestled him into rigid bar handcuffs, then pushed his head down towards his knees.

For up to 40 minutes they restrained him— as the other passengers boarded, as the crew performed the safety presentation, as the plane pulled away from the stand.

Jimmy Mubenga cried out repeatedly that he could not breathe, that the guards were killing him. Then he fell quiet. Then he stopped breathing. Nobody helped him until perhaps half an hour later, when paramedics rushed on board, lifted him out of his seat and onto the floor, and commenced CPR. It was too late.

I’m a reporter. Jointly, with the acclaimed journalist Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi, I run an investigative journalism project called Shine A Light. We’ve written and published a great deal about preventable deaths in state care. Jimmy Mubenga’s death was more than a private catastrophe for him and the people who loved him. His death speaks volumes about structural injustice, institutional racism, state and corporate impunity. (To mark this eighth anniversary, I produced a Twitter thread that has provoked shock and distress. Please be warned, there is violent racist matter in what follows).

After Jimmy Mubenga’s killing, both G4S and the UK Border Agency (part of the Home Office) claimed he had just fallen ill on the plane. That lie might have held, but the Guardian got a tip-off. Its reporter Paul Lewis used Twitter to find witnesses, and passengers got in touch.

“I now feel so guilty that I did nothing,” said one passenger who gave Paul a detailed account of what really happened on the plane.

Jimmy’s killing was predictable and therefore preventable. For years, G4S and the Home Office had variously ignored, dismissed and failed to act upon warnings about dangerous restraints that private contractors were using, and the racist abuse that went on — warnings from people who’d been harmed, from their doctors and lawyers.

The charity Medical Justice published a dossier of evidence in 2008, called Outsourcing Abuse. Two years later, the Border Agency’s chief executive Lin Homer responded, accusing the report’s authors of “seeking to damage the reputation of our contractors”. Seven months after that, Jimmy Mubenga was dead.

Before Jimmy, so many others had already been harmed in the care of G4S and the Home Office.

Six months before Jimmy died, a 39 year old Kenyan asylum-seeker called Eliud Nyenze collapsed and died at Oakington, a G4S lock-up in Cambridgeshire.

1/ Eight years ago Jimmy #Mubenga was unlawfully killed during a UK Border Agency attempt to deport him. Jimmy was 46. He had 5 children. Private security guards from #G4S restrained him until he died. pic.twitter.com/oI5OP8a2ie

— CLARE SAMBROOK (@CLARESAMBROOK) October 13, 2018

One year before Jimmy died, a little girl, forcibly arrested and locked up, only to be let go, arrested and locked up again, got predictably distressed and tried to strangle herself at Tinsley House, another G4S “business unit” (that’s what they’re called) near Gatwick Airport.

This has been happening across the world, too. In Australia’s goldfields, two years before Jimmy died, the Aboriginal elder Mr Ward was cooked to death in a G4S prison van with faulty air conditioning and a CCTV camera that didn’t work. Western Australia’s prisons inspector had warned years earlier that such vans were “unfit for humans”. The driver’s mate said they knew the van was unreliable, but that if they’d refused the job, the supervisor would have given it to someone else.

Back in England, six years before Jimmy died, 15-year-old Gareth Myatt, less than five feet tall and 6½ stone, was restrained to death in a G4S child prison. An inquest jury returned a verdict of accidental death. There were no criminal charges.

The coroner, Judge Pollard, wrote personally to then justice secretary Jack Straw to warn him about dangerous restraining methods, and about G4S management’s failure to act on reports of abuse.

One six-foot, sixteen-stone guard who had restrained Gareth got promoted to the post of Health and Safety manager at G4S children’s homes.

What of the three G4S guards who restrained Jimmy Mubenga? The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) at first decided not to prosecute, a decision Lord Ramsbotham, former Chief Inspector of Prisons, called “perverse”.

At the inquest into Jimmy Mubenga’s death, in May 2013, the coroner, Karon Monaghan QC, asked two of the guards — Terrence Hughes and Stuart Tribelnig — to read out some of the violent racist material they had on their mobile phones. Here’s one of the milder jokes: “What’s the difference between a cricket bat and a teatowel? Fuck all. They both wrap round a Muslim’s head nicely. Happy St George’s Day.” (No racist material was found on the mobile of the third guard, Colin Kaler).

The inquest jury concluded Jimmy’s death was “unlawful killing”. The coroner noted the “unhealthy culture” and “endemic racism” at G4S.

After that, the Crown Prosecution Service had to prosecute the guards for manslaughter. But the trial judge ruled the racist texts inadmissible, and withheld the inquest’s “unlawful killing” verdict from the trial jurors, who then acquitted all three men. (The judge told jurors not to worry if they later read about evidence excluded from the trial).

Incidentally, Jimmy Mubenga was from the heart of Angola’s diamond-mining region, which had been exploited by British interests for decades and where, as the writer Lara Pawson noted, “private security companies mete out appalling cruelties every day”.

British Airways played a part in Jimmy’s death. Members of the cabin crew witnessed Mubenga being restrained, heard him cry out. Yet nobody challenged the guards. The purser sent a message to the captain, who reckoned Jimmy was “faking it”. There was a defibrillator on board. Nobody thought to use it.

Since Jimmy Mubenga’s death, much of the deportation business has been moved to chartered airlines. People are still restrained, subjected to racist abuse, but this is now taking place on secret flights with rarely any independent witnesses aboard.

On one flight to Nigeria and Ghana in November 2013, guards from the Home Office contractor Tascor (part of Capita) put a Nigerian woman who was mentally ill in leg restraints for 10 hours and 5 minutes, and in handcuffs for 14 hours 30 minutes. On arrival in Lagos, standing naked on the runway, she took an overdose. The only reason we know this was that prisons inspectors happened to be on the flight, and their findings were later reported by Phil Miller.

The Home Office’s name for its charter flight programme? “Operation Majestic”.

In March of last year, fifteen protesters succeeded in stopping one such deportation flight. The Crown Prosecution Service has since charged them with terror offences. Amnesty International is currently observing the #Stansted15 trial, its director, Kate Allen,declared:

“Public protest and non-violent direct action can often be a key means of defending human rights, particularly when victims have no way to make their voices heard and have been denied access to justice. Human rights defenders are currently coming under attack in many countries around the world, with those in power doing all they can to discourage people from taking injustice personally. The UK must not go down that path.”

While agents of the state who have been involved in unlawful killing, or reckless “accidental death”, time and again, enjoy impunity, human rights defenders choose to risk arrest, prosecution, loss of liberty. The terrible death of Jimmy Mubenga shows what can happen when, in the face of state violence, people do nothing.

1 Comment

Marilyn Davies

Please keep me informed of Shine a Light investigations and how to stay informed and involved.