Hakim Bey: Chaos, altered consciousness, and peak experiences An A to Z of Theory

Columns, In Theory, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Thursday, December 7, 2017 15:05 - 0 Comments

Ontological anarchist Hakim Bey argues that chaos is ontologically primary. Meaning can only be produced subjectively, through self-valorisation. In this third essay of the series, I explore the role of peak experience and altered consciousness in ontological anarchism. I examines how immediacy can provide a basis for resistance to alienation, explore Bey’s ethical theories, and look at whether social life is still possible if outer order is rejected.

Ontological anarchist Hakim Bey argues that chaos is ontologically primary. Meaning can only be produced subjectively, through self-valorisation. In this third essay of the series, I explore the role of peak experience and altered consciousness in ontological anarchism. I examines how immediacy can provide a basis for resistance to alienation, explore Bey’s ethical theories, and look at whether social life is still possible if outer order is rejected.

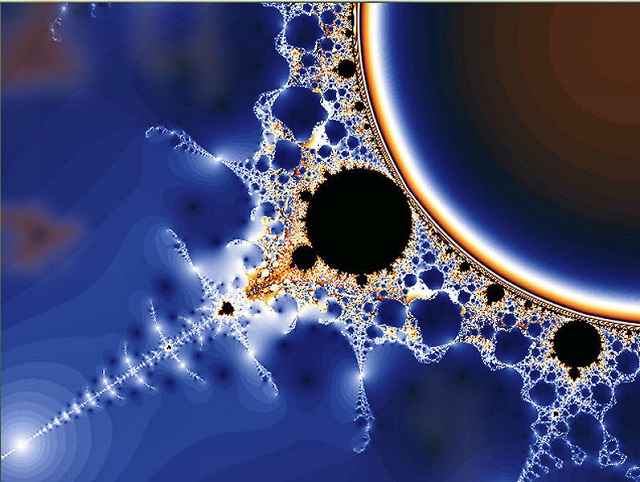

The orientation to chaos leads to a political theory of altered consciousness. In order to be felt as really meaningful and existing, something needs to interact with the body and with imagination. It needs to exist in the ‘imaginal’ realm – the realm of images, unconscious archetypes, and imagination. Bey seeks an intensification of everyday life – a situation in which marvellous, ecstatic, intense, passionate forces enter into life. The passions are not pale shadows of higher realities, as in Platonism, but are themselves supernatural realities. Everyday life can be raised or sublimated to ‘a degree of intensity approaching full presence, full embodiment – and yet still indistinct… an erotic dream of a utopian landscape’. A TAZ is a case of life ‘spending itself in living‘, rather than simply surviving. It can entail risking the abyss. This position involves a particular kind of affective politics. Bey clearly sees boredom or lack of meaning as the major problem in contemporary life.

Bey also proposes a particular path to creating meaning. Chaos means that anything ones does must be ‘founded on nothing‘. No solid groundings are possible. Yet still, we need projects, because we are not ourselves ‘nothing’. The project which remains is an uprising against everything that posits an essential nature of things. Anarchism is faced with a philosophical problem deriving from the contradiction between meaninglessness and ethics. It seeks a ‘right way to live‘ in an ‘absurd universe’. In ‘The Palimpsest‘, Bey distinguishes between theory – which drifts nomadically – and ideology, which is rigid, and creates cities and moral laws.

Ideology re-orders the world from outside, whereas theory refuses to let go of desire and thus creates organic movements. Theory is like a palimpsest, in which different texts are written over one another. The idea of theory as a palimpsest comes from Derrida. However, Bey is looking for ‘bursts of light’, moments of intensity, rather than Derridean ironies. He is seeking values, or the creative capacity to create values out of desires. Bey’s style of theory aims to be a ludic (play-based) approach. It is not moral relativism in the usual sense. A viewpoint is given value by a kind of subjective teleology – the individual’s search for purposes, goals, and objects of desire. The epistemology (way of learning and knowing) associated with this theory will involve juxtaposing distinct elements, rather than developing them consistently.

Awareness of chaos is intensified by altered states of consciousness and intense experiences, including those arising from psychedelic drugs, shamanism, meditation, and aestheticised living. Such practices are ways of sucking everything present into the Other World, the spiritual or chaotic world. They are attempts to reconnect with ‘original intimacy‘, prior to cognition. Without such ‘higher states of consciousness‘, anarchism dries up in resentment and misery. Hence the need for an anarchism both mystical and practical. Bey lists a wide range of possible sources of such intense, unmediated perception, including inspiration, danger, architecture, drink and sexuality. One passage refers to Iranian poetry set to music and chanted or sung, producing an affect known as hal – somewhere between hyperawareness and an aesthetic mood. Another passage refers to the techniques of heretics and mystics, seeking inner liberation. Some such techniques get trapped in religion, whereas others become revolutionary. Bey uses the term ‘magic’ or ‘sorcery‘ for practices which cultivate altered awareness and disrupt the false selves that result from ordinary perception. A sorcerer recognises the reality of consciousness. This leads to a state of intoxication. Sorcery is a set of means to sustain this state of being, and expand it to other people.

Such practices produce a particular relationship to the universe. True mysticism creates what Bey calls a ‘self at peace‘, a ‘self with power’. Awareness of the ‘immanent oneness of being’ is at the root of various anarchistic heresies such as the Ranters and Assassins. Another passage (from the Black Fez Manifesto) refers to the ‘potential of an idleness money can’t buy, the thrill of zilch, the zen of ZeroWork’. This idleness, ‘natural to childhood, must be strenuously defended’. Bey effectively calls for us to avoid being broken-in by capitalism, to remain in or return to a childhood orientation to play and immediacy. A shaman of bard uses a combination of words, music and archetypes to create altered consciousness. Everyone is an artist, but not necessarily all of the same type. Some might specialise in the ‘grand integrative powers of creativity‘ or telling the ‘central stories’ of the group. Such integration by bards is posited as an alternative to integration by laws.

Many fields of life are already inflected with altered consciousness. Hermetic powers have been appropriated by dominant institutions. The means to prevent such capture is to insist that each adept control the powers, rather than be manipulated through them. Bey periodically refers to Bakhtin’s ‘material bodily principle‘, or the valuing of the body in carnival, as typical of intensity. He counterposes the celebration of the body to gnostic body-hatred, which he believes is prevalent in the Spectacle. In a poem, Wilson suggests that animals already practice zerowork economics.

Bey suggests that language does not have to be representational. The structure of language may turn out to be chaotic, or complex and dynamic. Grammar might be a strange attractor, rather than a structuring law. Language is a bridge (of translation or metaphor) and not a structure of resemblance. Language should be ‘angelic‘ – similar to the figure of the angel as messenger or intermediary. It should carry magic between self and other. Instead it is infected with a virus of sameness and alienation. This virus is the source of the master-signifier in language.

In many ways, Bey’s work can be understood as a theory of alienation. Alienation (whether social, psychological or ecological) separates us from awareness of, and life in, ontological chaos. For instance, belief in order leads to normativities of good and evil, body-shame, and so on. The family is criticised for encouraging miserliness with love. Christianity, even in its liberationist variants, is condemned. The point is to seize back presence from the absence created by abstraction. Life belongs neither to past nor future, but to the present. Idealised pasts and futures are rejected as barriers to presence. Time can become authentic and chaotic by being released from planned grids.

Bey criticises negative ontology, in which he apparently includes much of poststructuralism, for flattening reality onto a single, level plain. This process makes altered consciousness and escape from capitalism difficult. Everything becomes equally meaningless. Negative consciousness is a predictable effect of the present system. But for Bey it is a kind of ‘spook-sickness’ caused by alienation. It serves the status quo, because it keeps people afraid, and reliant on leaders for salvation. This makes attacks on leaders seem stupid. It creates a binary between pointless action and sensible passivity. This argument is similar to my own work on theories of constitutive lack.

Chaos is misappropriated when used as a scientific basis for death, as nihilism, or for scams. Chaos is everywhere, and so is unsaleable. At one point, Bey argues that both New Age spirituality and religious fundamentalisms derive their power from the spiritual emptiness of modern life. However, they divert the rejection of emptiness into new abstractions – commodification in the New Age, morality in fundamentalism. Escaping spiritual emptiness instead requires escaping abstractions.

Bey specifically rejects the view of chaos as lack, entropy, or nihilism. Instead, he argues that chaos is Tao, or continual creation. It is a field of potential energy rather than exhaustion, of everything rather than nothing. Bey speaks of moments when he’s overcome the feeling of powerlessness and futility. He writes that these are the only times he breaks through into a state of consciousness which feels like health. In other words, action is necessary to disalienate, even if it has no outer effect. Existence is a meaningless abyss. Yet this is not cause for pessimism. Rather, it leads to an open world in which we can create or bestow meaning through action, play, and will.

Bey seeks to make an offer of disalienation, which, once felt, breaks the functioning of capitalism. Even a few moments of joy may be worth considerable sacrifice. Awareness of the holism of being, or ‘metanoia‘, can go beyond categorised thinking into smooth, nomadic, or chaotic thinking and perception. Bey denies that he is pointing to a secret which he is refusing to share. Rather, the material bodily principle is secret because it is forgotten. The body is degraded both by the world of images and by bodily narcissism.

Immediacy, or presence, is a central concept for Bey. Immediacy is valued as a counterpoint to representation and simulation – which are definitive of the dominant system. Immediacy can also be expressed in or through representation, by means of chaotic processes which disrupt order. The spirituality of pleasure, as Bey terms it, exists only in a presence which disappears if it is represented. In Bey’s reading of religious imperatives, such imperatives are not outer impositions but a kind of inner choice – to live fully, or to risk dying without having lived. The point seems to be to experience chaos as play, rather than trauma. ‘The universe’, Bey states at one point, ‘wants to play‘. One loses one’s humanity or divinity if one refuses to play. People sometimes refuse to play due to alienated motives ranging from dull anguish to greed to contemplation. The ‘magic’ practices of Bey’s politics are ways of experiencing chaos in a suitably joyful way. In Scandal, Wilson argues that one can handle pain, suffering and negative emotions by ritualising them, turning them into reversible symbols. Cultures also symbolise and channel the potentially destructive power of Eros. Bey insists that this approach does not deny that there are ugly, frightening things in the world. However, many of these can be overcome. They can only be overcome if people build an aesthetic from overcoming rather than fear. If one reads history through ‘both hemispheres‘ – meaning both affectively and logically – then one realises the world constantly undergoes death and rebirth.

If life is chaos, then Bey’s response is what he sometimes terms ‘aimless wandering‘ or nomadism, and compares to the Situationist drive and Sufi ‘journeying’. Nomadism, along with the Uprising, provides a model for everyday life. In Sacred Drift, Wilson invokes the figure of the ‘rootless cosmopolitan’, a Stalinist slander against Jews, as a general modern strategy. People wander or drift today because nothing fixes them in place or commands fixed loyalties. This process of movement is also a kind of psychological nomadism which moves among different bodies of theory. There is an ambiguity in that, since being is oneness, journeys start and end in the same place.

For Bey, life is to be lived through peak experiences, and conviviality. The peak experience becomes the goal of aimless wandering, much like a shrine is the goal of a pilgrimage. Bey’s concept of peak experience is modified from Maslow’s. Against the false unity of a flattened, commodified world, Bey argues for disloyalty to the dominant culture and nomadic movement among different alternatives.

In a poem in the Black Fez Manifesto, Bey cites Ibn Khaldun’s view that nomads who awake at night to see the stars are like animals reassured the universe is still there. But he adds that city-dwellers who awake similarly while on a trip are sucked into ‘panic’ and ‘freefall’. The point here seems to be that the experience of chaos is negative only because of the habits and alienation of modern subjects. Embracing chaos is not a loss in itself, but seems as such from a certain point of view, because of a lack of familiarity with chaos. Modernity or the Enlightenment tries to blot out the stars with light pollution, to destroy the vitality of night. Night here symbolises a type of energy associated with smooth space and altered consciousness. In a related piece, Bey calls for a ‘Bureau of Endarkenment’ to encourage superstitions about technologies such as cars and electricity.

Ethics and society

Like other post-left and politics-of-desire writers, Bey rejects normativity and top-down morality. Instead, he argues for a type of immanent ethics based on one’s own desire and ethos. In a fragment on crime, Bey defines justice as action in line with spontaneous nature. He argues that it cannot be obtained by any law or dogma. The moment someone discovers and acts in line with a mode of being different from alienated reality, the state or ‘law’ tries to crush it. This means that we are all criminals. Instead of claiming martyrdom as victims of persecution, we should admit that our very nature is criminal.

Ontological freedom stems from ontological chaos. We are already sovereigns in our own skins, by virtue of the absence of order. Freedom is not, therefore, something we have to achieve through revolution or struggle. Freedom is realised in the experience of intensity, or emotion experienced to the point of being overwhelmed. Bey supports Fourier’s idea that unrepressed passions provide the only basis for social harmony. However, people also seek other sovereigns (i.e. other autonomous subjects) for relations. Reciprocity, or pleasure with others, is the non-predatory expansion of intensity. It is a kind of eros of the social. In one passage, Bey argues that ‘each of us owns half the map‘, so finding intensity is often a cooperative activity. He suggests that the self/other or individual/group contradictions are false dichotomies created by the Spectacle. Self and other are complementary. The Ego and Society are absolutes which do not exist. Rather, people are drawn into complex relations in a field of chaos. Bey refers to Stirner’s union of self-owning ones, Nietzsche’s circle of free spirits, and Fourier’s passional series as inspirations for such relations. They involve processes of redoubling oneself as others also do so. The ‘gratuitous creativity’ of such a group would replace the specialised field of art.

In a sense, Bey is constructing a virtue ethics very different from the usual type, in which virtuous life consists in the pursuit of peak experiences and a type of living compatible with ontological chaos. Some readers see Bey’s politics as emphasising sincerity as a virtue. In such a worldview, enjoyment is almost a moral imperative. One has an obligation to experience joy, and not postpone it to the future or afterlife, so as to do justice to oneself. In Sacred Drift, Wilson argues that this is a prerequisite for doing justice to others. By combining various Sufi theories of disalienation, Bey suggests that we arrive at a position which valorises all kinds of sexualities, both as permitted bodily enjoyment and spiritual practice.

Bey, following Bob Black, favours the abolition of work. The subset of work-like tasks which remain necessary are to become a kind of play for those attracted to them. Bey thinks that relations among autonomous beings might find ways of working themselves out. He sometimes suggests that we are all ‘monarchs’ or ‘sovereigns’. Today we survive as pretenders, but we can still seize a little reality for ourselves. Monarchy is closer to anarchy than other forms of government, because it recognises individual sovereignty. Bey here plays on the Situationist idea of ‘masters without servants’, which is an egalitarian attempt to address hierarchical aspects of Nietzsche.

However, this does not mean that people should optimise their own enjoyment in predatory ways. The point is to realise intensity in altered consciousness, not to appropriate alienated experiences in a maximising way. In ‘The Anti-Caliph‘, Wilson distances his position from ‘libertinism’, in the sense of doing what one likes regardless of others’ values or lives. The difference between an antinomian (Wilson/Bey’s position) and a libertine is that the former acts from a personal ethic. This ethic is considered higher than outer laws and social norms, and thus provides a basis for defying them. Such an ethic is more demanding than normativity or law, since it involves the expansion of the self to include others, rather than self- or other-denial.

‘A freedom or pleasure that rests on someone else’s slavery or misery cannot finally satisfy the self because it is a limitation or narrowing of the self, an admission of impotence, an offence against generosity and justice’.

Bey does not want to realise desires at the expense of others’ misery – not for moral reasons, but because it is self-defeating. Misery breeds misery, and desires to cause misery stem from psychological impoverishment. He is sympathetic to Fourier’s argument that desire is impossible unless all desires are possible. Everyone aspires to certain ‘good things‘ which are available only among free spirits. This is particularly true in cases of love. The spiritual meaning of sexuality, for instance, precludes uncaring, violent and dominating types of sex. Bey thus advocates the destruction of all social relations which treat some as subordinate to or owned by others – including marriage and the family. One’s sexual code should be ‘both highly ethical and highly humane’, valuing both pleasure and conviviality. It should include a spiritual dimension, and not succumb to ‘joyless commodification’ or ‘vulgar materialism’. Such an ethic is distinct from normativity, and continuous with shamanism. For instance, Bey remarks that paganism invents virtues, but not laws.

‘Wrong’ in Bey’s code of ethics means counterproductive and self-immiserating. Causing misery to others is wrong because it is self-defeating (misery breeds misery). Those who immiserate others are in Bey’s experience psychologically poor, and themselves miserable. Bey associates de Sade with fascism – the satisfaction of desires of an elite through the creation of enemies and victims. Against these positions, Bey turns to Fourier’s view that desire is impossible unless all desires are possible. This seems to be partly a response to Bookchin’s critique. It is a similar critique of simple egoism to that found, for instance, in Ancient Greek thought, which similarly argued for ethical positions without assuming a standpoint higher than the self.

Other passages also emphasise the relational aspect of chaos and becoming. For instance, Bey argues that speech is dialogical or ‘diadic’ in structure. It relies on a pairing of speaker and hearer, and this pairing can be reversed. In Sacred Drift, Wilson argues for reciprocity, sharing, mutual benefit, and harmony, instead of either quarrelling or submitting. In ‘Utopian Blues‘, he claims that utopia is a unity, not a uniformity. It is based on something like Fourier’s idea of harmonisation – a combination of widely different people and desires, through each pursuing their own attractions. Utopian desire ‘never comes to an end, even – or especially – in utopia’.

The primary conflict of the current world is the conflict between the authority of the tyrant and the authority of the realised self. In Ec(o)logues, Wilson claims that social life is to be based on conviviality and creativity, rather than mediation. A key step towards a different way of being is to summon the will to experience other living beings as relatives or relations. The valuation of a different kind of world is crucial here. Many people are forced to live by means of conviviality or social networks due to poverty (for instance, collective squatting). They don’t necessarily value such practices. However, ontological anarchy values such a way of life as preferable to mass consumerism.

At times, the imperative to support chaos and promote freedom lead to ambivalent positions. For instance, Bey is ambivalent about abortion, supporting women’s freedom but desiring that the entropic force of family planning be negated by chaos. This position does not imply optimism about human nature. Bey opposes the view that humans are ‘basically good’. Instead, he argues against others holding power ‘precisely because we don’t trust the bastards’. In another passage in Sacred Drift, he argues that brilliance is not itself desirable. He observes that people can be brilliant for good things like love or humanity, but also for bad things like hatred and self-aggrandisement. In the latter case, there is a need for self-defence against brilliance. The best of human potentiality seems to come out in altered consciousness, whereas capitalism stimulates the worst.

For the other essays in the series, please visit the In Theory column page.

Editor’s note: With regards to Hakim Bey’s controversial personal stances, these will be discussed in Part 10 of this series. In the meantime, please read our ‘Note to readers’ at the end of the introductory essay of the series.

Leave a Reply