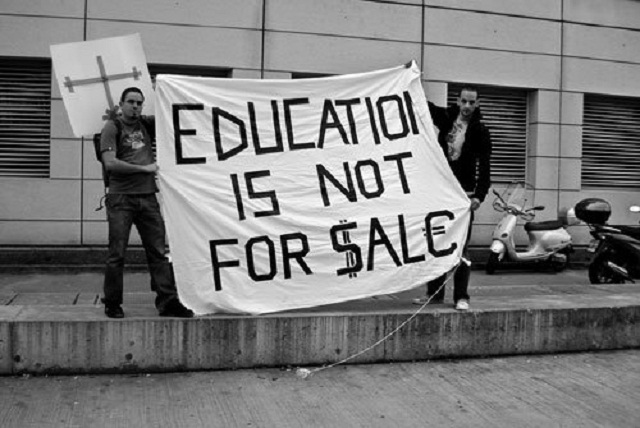

The future of the University lies in challenging, not adopting, free-market dogma Ideas

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Thursday, December 13, 2012 3:52 - 1 Comment

By Neal Curtis

In 1979 the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard published a ‘report on knowledge’ entitled The Postmodern Condition. In this report, commissioned by the Conseil des Universitiés of the government of Quebec, Lyotard argued it was no longer the grand narratives of Idealism and Republicanism, which respectively saw knowledge as a good in itself and a significant contribution to the furtherance of freedom, that gave legitimacy to knowledge, but a regime of technical competence whereby knowledge was determined “good” or “true” if it resulted in the better operations of capitalism. “Good” knowledge would therefore be commodifiable and contribute to the production of surplus value, and in this way increase the overall performance of the system. As Lyotard concludes: ‘An equation between wealth, efficiency, and truth is thus established’.

In 1979 the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard published a ‘report on knowledge’ entitled The Postmodern Condition. In this report, commissioned by the Conseil des Universitiés of the government of Quebec, Lyotard argued it was no longer the grand narratives of Idealism and Republicanism, which respectively saw knowledge as a good in itself and a significant contribution to the furtherance of freedom, that gave legitimacy to knowledge, but a regime of technical competence whereby knowledge was determined “good” or “true” if it resulted in the better operations of capitalism. “Good” knowledge would therefore be commodifiable and contribute to the production of surplus value, and in this way increase the overall performance of the system. As Lyotard concludes: ‘An equation between wealth, efficiency, and truth is thus established’.

While Lyotard certainly overlooked the fact that wealth and truth had always been very close kin, his analysis of the marketisation of knowledge was prescient. Although neo-liberal philosophy was well known in French academic circles when Lyotard published his report, as can be seen in Foucault’s lecture course from that year published under the title The Birth of Biopolitics, it was the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 that signaled the beginning of the neo-liberal revolution that would dramatically re-shape the society we know today and establish a new “common sense”. This was a revolution that saw the financialisation of the economy, the emergence of a credit-fuelled consumer culture, and large-scale privatisations of utilities and services.

In this climate it was assumed that higher education should also be subjected to the purifying discipline of market competition. From that point on the university became increasingly subject to the vacuous discourse of “Excellence”, with its culture of technocratic compliance and consumer-based customer service, within which the relations between students and academics as well as academics and their research have been slowly transformed. Today, with so much public money having been used to contain the biggest ever crisis in private speculation, the limitations on current public spending are once again being used by free-market ideologues to further entrench the dogma of privatisation.

In this context the Australian government commissioned its own report published in 2012 under the title ‘University of the Future’ arguing that deliberations concerning any future model for higher education must address ‘the ideal role of the university within the education and research value chains’, but given those value chains are signaled by relevant ‘customer segments’ and ‘optimal channels to market’ it very quickly becomes clear that we are working with a restricted sense of value in keeping with the strictures of neo-liberal doctrine.

Tellingly, the Australian government didn’t ask a philosopher to compile the report, they didn’t even ask an academic. Instead they saw fit to ask the accountancy firm Ernst & Young. The logic, of course, is quite simple. Over the course of the last 33 years the complex social accountability of an institution like the university has been reduced to a problem of economic accounting and, like any other business, the viability of its future rests solely in its business model. The irony that the fate of a public institution should be placed in the hands of a company whose very purpose is to ensure the minimal movement of private wealth to the public purse, let alone a company involved in balance sheet manipulation at Lehmann Brothers just before they collapsed in 2008, is entirely lost on the report’s author, but then again he doesn’t seem to be that sensitive to irony.

In the introduction the author offers the ‘drivers of change’, which are supposed to explain why universities ‘should […] transition’ from the publicly funded model, as evidence of a ‘brave new world’. I imagine this phrase is used to invoke a sense of the supposed advancement and opportunity afforded by the new reality in line with the fetishisation of entrepreneurial innovation out of which it speaks, but for most people this phrase is associated with Aldous Huxley’s dystopian vision of an authoritarian future, a connotation that I do not think the report intended.

Alternatively, and no doubt Huxley’s inspiration, the phrase is known from a speech of Miranda’s in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Here, due to the effects of her social isolation she views a shipwreck and its bedraggled, drunken sailors as a thing of beauty and wonder, declaring: ‘How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world’. However we interpret the brilliantly ambiguous nature of this line within the context of the play as a whole it must be read as the product of a very partial and particular perspective. Again, in a report that presents the free market as a new reality—the way the world is—this reference to partiality and a radically particular vision sits rather awkwardly with any claim to “realism”.

Perhaps, however, the author is genuinely joyful. As is well known, crisis is endemic to the capitalist system and economic crashes, while being incredibly destructive, are also the source of new rounds of accumulation as those that survive grow even stronger on the “fire sales” that follow. It is now commonly recognised that the victors in the financial crisis of 2008 were the banks, and this report represents further opportunities for profit now that so much pressure has been placed on public sector funding. Universities have been weakened by the bail out, but still provide significant pathways to profit for private speculators.

The report, before anything else, is thus an attempt to take advantage of this weakness to open up new exploitable resources. The added significance of this is that many of the academics working within these institutions operate outside the neo-liberal group think, making the university the only social institution to have not yet been appropriated by the “common sense” of marketised solutions. In this sense, the report describes further ways in which research and teaching can be increasingly tied to that “common sense” in order to eradicate the friction and noise, and therefore the inefficiencies, that alternative interpretations of the world feed into the system.

The partiality of the report has little time for one of the first rules of academic research, especially of this empirical, data-driven kind, which is to have some critical sense of one’s own position as a researcher and how that position might impact upon your conclusions, but we are clearly not in the realm of good academic practice here. The fact that the report can make such bold claims for radical changes to a globally diverse public institution, based on only 40 interviews with ‘senior executives’, would ordinarily be a cause for concern. As a methodology it should trouble even an examiner of an undergraduate dissertation and would certainly be rejected from academic journals as research whose claims far exceed the limitations of the data on which it is based.

The point, however, is that good research is now that which contributes to the greater efficiency of the system, and in this proposal to streamline universities via the market model, this research does everything it can to remove the annoying, messy friction that socially complex and polyvalent institutions like universities tend to produce. Interestingly, this kind of naked ideological proselytising is a far more significant ‘driver of change’ than any of those listed and yet it remains hidden (or at least tries to).

The partiality of the research is therefore evident in the absence of any critical stance towards its own frames of reference, which are simply set out as descriptions of a given reality. The ‘drivers’ that are listed amount to the following: ‘democratisation of knowledge and access’; ‘contestability of markets and funding’; digital technologies’; ‘global mobility’; and ‘integration with industry’.

I will focus on the issue of democracy below, but ought to perhaps start with the fact that the only place the report concedes any form of conflict or contestation is in the ‘contestability of markets’. For example, these descriptions of the world are never presented as something that might be contestable nor is it assumed that the world these descriptions supposedly represent could be challenged. In other words, no thought is given to the perfectly plausible idea that the world we live in ought to transition and not the university, let alone the blasphemy that the university might actively play a part in enabling such a social, political and economic transition beyond the free market dogma that captivates those that govern us.

Of the others, ‘global mobility’ refers to the ‘diffuse sources of academic talent’, suggesting that universities no longer have captive markets, and yet no account is given of the increasing number of ‘stay-at-home’ students who can’t afford to leave their parents’ home due to cuts in public support for degrees. ‘Digital technologies’ then simply assumes the way forward is massive on-line, distance-learning courses offered by leading brands names, but also suggests a division of labour in which private providers can ‘specialise in parts of the value chain’ such as content generation and certification. This would also be a key element of ‘integration with industry’ where ‘scale and depth of industry based learning’ will be ‘a source of competitive advantage’.

Overall, the conclusion is that universities ‘will increasingly be run like corporations, while seeking to maintain the freedom of inquiry’ that ensures their continued reputation. How that freedom is maintained under the unitary social goal of profit is not addressed. Is it not more likely that as the university is assimilated into the corporate ethos and takes on corporate partners we will hear more stories like that of Joseph Hanlon at the Open University, as reported in the THE, who has been banned from using the documents of an international agribusiness firm in his research for fear the firm will sue the university. This is only one example, but integration with industry is not an unquestionable good and is perhaps more in keeping with the condition I have elsewhere described as “idiotism“.

The ability to critique and challenge takes us to the heart of the idea of democracy. If democracy is anything it is defined more by dissensus than consensus. We may agree to disagree as the popular phrase has it, but disagreement is the key. Traditionally neo-liberals have posited the market as a means for mediating this disagreement and yet it has increasingly become a means of closing down disagreement or framing social issues within marketised solutions. This is a system that is also overseen by a largely unaccountable oligarchy of financeers, corporate bosses, media moguls and sympathetic politicians that Alain Joxe has called a ‘new aristocracy’, a counter-revolutionary class actively rolling back the democratic gains of the last two centuries.

It is pertinent, then, that the Ernst & Young report reduces democracy to access. This is very much in line with the consumer model of democracy that privileges choice (irrespective of whether or not the choice represents a substantial difference) and the immediate gratification of desire. Access, like the “excellence” that has come to dominate university practice in the age of markets is entirely meaningless. Access requires secondary judgements if it is to have any meaningful content. Access per se is not democratic and a lack of access is not necessarily undemocratic.

In fact, Jürgen Habermas, who for many years advocated for the centrality of the public sphere in democratic deliberation, argued that public means an openness that doesn’t necessarily entail a ‘general accessibility’. What we have under the increasingly dogmatic conditions of neo-liberalism in which options are closed down in favour of marketised solutions is access without openness. Therefore, as an academic working between the humanities and the social sciences the idea that democracy might be reduced in this way especially in relation to the university is troubling to say the least.

For democracy to mean anything it must include the possibility that the interpretation of the world as it is given is thoroughly contestable; that alternatives might be invented and brought into being. However, in keeping with the ideology propounded by the report’s author the supposed end of history and the victory of free market capitalism has put an end to any such contest. Speculation as to what we might mean by the Good Society is idle and inefficient. The task of what Bill Readings called the ‘post-historical university’ is to concentrate on how to align itself with and facilitate improvements in the system as it is given.

The paucity of democracy as understood by the report’s author is clearly in evidence when he notes how several of the interviewees do not actually agree that universities will need to change all that much. Without considering why they might contest this declaration of the need for privatisation he simply writes: ‘We cite the Darwinian force of the market and innovation’. Democracy is thus subjected to the rule of biological determinism, and innovation, or the breadth of human inventiveness and creativity, is reduced to the model of corporate entrepreneurialism.

Again, the irony seems to pass unnoticed. Even if we did rely on some reduced form of Darwinism to measure all things human we would, of course, need to note that an unregulated market of purely private interests showed itself to be entirely unfit, and that without a huge intervention from the state and the public purse it may well now be as dead as a dodo. If any evolutionary model is relevant here it is Kropotkin’s model of mutual aid! The free market was always a conceit but now we are asked to believe that the future of the university lies in playing its part as life support to a discredited ideology. The report vigorously seeks to promote privatisation and the assimilation of the university to corporate imperatives and yet, in its limited vision, its dogmatic approach, and its unthinking support of economic power it precisely, yet unwittingly, outlines what sort of university is needed in the future: open, public, polyglottal, independent, and intellectually rigorous.

1 Comment

Database of Articles and Websites on the Privatisation of Education « Sussex Against Privatization

[…] – The future of the University lies in challenging, not adopting, free-market dogma https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/future-university-lies-challenging-adopting-free-market-dogma/ […]