Against the Cyborg Gaze: On Forward Intelligence Teams Contours of control

Contours of Control, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Tuesday, August 28, 2012 19:26 - 2 Comments

By Alan More

“many activist groups believe FITs to be a deliberate tactic of intimidation in order to disrupt and deter lawful dissent” (Photograph: Marc Vallée)

Increasingly, today’s security-obsessed culture of control engenders the creeping criminalisation of almost any public assembly not preoccupied with consumption. Last month saw the violent mass arrest and detention of cyclists for daring to breach conditions imposed under an Olympic state of exception.

As events unfolded, few would have noticed the police photographer surreptitiously shooting from a nearby vantage point. Yet this cyborg gaze of the state – part human, part machine – lies at the fine end of a spectrum of tactics deployed in the front line of a total war against “domestic extremism”, an ominous-sounding yet poorly defined category, and one which is increasingly applied to any and all forms of dissent.

Enter the crepuscular world of police Forward Intelligence Teams (FITs). For the uninitiated, FITs are units comprising both uniformed police officers and (also uniformed) civilian photographers, tasked with conducting overt surveillance of the public during “public order events”. First introduced in the mid-90s in order to gather evidence against football hooligans, FITs’ scope has since been broadened to include political demonstrations and meetings, with their primary role now being to identify and obtain information about protesters.

In recent years FITs have become a source of growing controversy due both to the deliberately intrusive and often underhanded manner in which surveillance is conducted, as well as issues surrounding the subsequent retention of data by the police. In 2009 it was revealed that the personal details of thousands of peaceful and legal protestors had been collated along with photographs and video footage and entered onto a clandestine national police database.

A recent HMIC report concludes that both the justification and legal basis for the use of FITs is unclear. Indeed, judged against their ostensible remit of intelligence-gathering, FITs appear somewhat superfluous given the abundance of so-called “open source intelligence” furnished by the UK’s ubiquitous CCTV infrastructure. As one industry publication puts it:

As the most spied upon nation in the world, with over 4.3 million cameras in operation, the UK’s police forces are spoilt for choice.

This, of course, is in addition to the ongoing infiltration of activist groups by undercover police, as well as recently announced plans to allow police and security services to monitor email and social media communications. Furthermore, police forces such as the Met seem strangely reluctant to use footage obtained by FITs as evidence in court.

Given all this, it is hardly surprising that many activist groups believe FITs to be a deliberate tactic of intimidation in order to disrupt and deter lawful dissent; a form of “soft-line” counterinsurgency. Whether this function is simply an unintended consequence of bureaucractic politics and “function creep”, or a more calculated directive from one of the Met’s shadowy COINTELPRO-style public order intelligence-gathering units, one can only speculate.

There is undoubtedly something viscerally hostile or antagonising in the act of photographing or filming someone against their will, that whilst perhaps tacitly understood is rarely articulated. FIT surveillance is consistently described by protesters as “intimidatory”, “intrusive”, “invasive” and “provocative”. Moreover, a cursory YouTube search reveals numerous instances of police officers taking offense and even threatening to arrest members of the public for filming them, despite this being completely legal.

In thinking about photography’s mysterious power to provoke such reactions, one is reminded of the old colonial cliché of the native who fears that the camera will ‘steal his soul’. In fact, this stereotype is not unfounded: in many different cultures, anthropologists have encountered the belief that photographs capture the shadow, or soul, of their subjects, and give the photographer power over those whose picture he has taken.

Western thinkers, too, have regarded photography, and vision more generally, with a deep-seated mistrust. From Sartre’s indictment of “the look” to Foucault’s famous reinterpretation of Bentham’s “diabolical” panopticon, vision has been seen as a force of domination and control, and visibility equated with subjection.

The French literary theorist and philosopher Roland Barthes described the experience of being photographed, and the apprehension of oneself as an image, as mortifying; the metaphorical death of the subject. In more concrete terms, Susan Sontag, arguably the first to draw attention to photography’s potential as a tool of power, has famously asserted that ‘there is an aggression implicit in every use of the camera’:

To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they can never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed. Just as a camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a sublimated murder – a soft murder.

There is a violence – subtle, incomplete, and evasive – inherent to photography. Moreover, this is qualitatively intensified under the condition of state compulsion and coercion: Section 60aa of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act (1994) – routinely invoked by FITs – gives police officers powers to remove items of clothing worn for the purpose of concealing individuals’ identity, using force if necessary.

The continued use of FITs flies in the face of recommendations made, following the heavily-criticised policing of the 2009 G20 protests, that the police should “nurture the British model of policing”, with an emphasis on winning public consent.

At a fundamental level, the unblinking “gaze without eyes” of the surveillance camera denies its targets even the basic human reciprocity of eye contact, imposing an inherent distance and inequality between photographer and subject. The surveillance camera, much like the Panopticon, in Foucault’s words, “dissociates the see/being seen dyad”.

It is for this reason that, emotionally, there is a great difference between being looked at by someone directly and being looked at through the lens of a surveillance camera. As one protestor I spoke to put it, “There’s something very inaccessible about FITs; there’s no human-to-human empathy. All you see is the camera and uniform”. Importantly, this dissociation also produces a qualitatively different way of seeing for those behind the lens: surveyed people, insofar as they cannot return eye contact, always appear somewhat suspect.

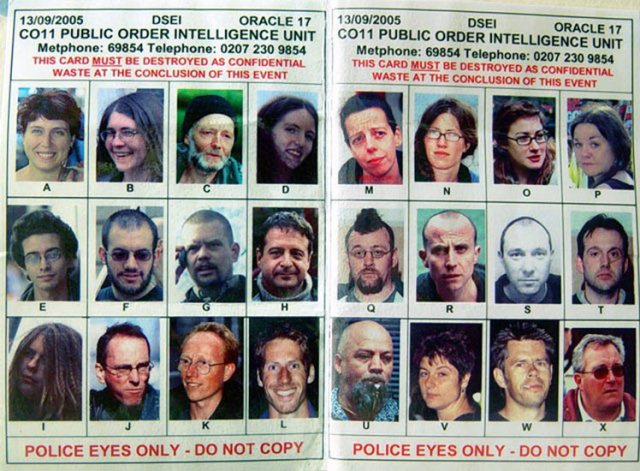

Here we encounter something akin to UAVs dehumanising “drone stare”; protestors are objectified and extracted from the context of political struggle, rendered simply as “targets” for surveillance. This is perhaps most clearly exemplified by a leaked “spotter card” (shown below), used by FITs during a demonstration in 2005.

Here, protesters are abstracted, isolated, and individualised; stripped of their surroundings, these images assume the status of a mere index or “evidence” of imagined future crimes. Evocative of the conventional framing of police mugshots, protesters’ inclusion in this veritable rogues gallery effectively amounts to a form of a priori criminalisation.

“protestors’ inclusion in this veritable rogues gallery effectively amounts to a form of a priori criminalisation”

This begins to capture something of the essence of “Forward Intelligence”. Whilst George Orwell’s 1984 has for some time served as a stock metaphor for any and all manifestations of the “surveillance state”, the political reality of Philip K. Dick’s Minority Report and the twilight world depicted in Franz Kafka’s The Trial provide far more pertinent frames of reference.

FITs and their younger sister initiative, “Evidence Gathering Teams”, are premised on a Minority Report logic of pre-crime. Furthermore, that individuals’ names, photographs and personal information are collated and consigned indefinitely to a restricted database to be monitored, scrutinised and targeted for potential future intervention, seems inevitably geared to produce something corresponding to Mark Poster’s notion of “database anxiety” – the uneasiness engendered by the awareness of being constantly surveilled.

Such a situation is truly Kafkaesque, reminiscent of The Trial’s shadowy officials, who are “in the know” because they have access to files and whose enigmatic activities keep their suspects, unaware of the nature of the charges against them, in a constant state of apprehension. That protesters themselves are all too often arbitrarily and wrongfully arrested, charged and prosecuted can only exacerbate such effects.

Ultimately, FIT surveillance cannot be understood apart from a far broader range of pre-emptive informational, psychological, legal and spatial control tactics, which function to disrupt, deter and criminalise lawful and democratic dissent. This spectrum of activities ranges from the imposition of ‘no-protest zones’ and the massive presentation of force on the streets; to police verbally abusing and calling activists by their first names; to surveillance of and unannounced visits to activists homes; to undercover infiltration of political groups; to raids of activist meeting spaces; to unlawful arrests, searches, seizure and detention; and to police violence against activists and journalists.

In the coming weeks I’ll be tracing some of these contours of control, as well as considering in turn the manifold, innovative and audacious ways in which they are resisted.

Next column: Counter-surveillance – Watching the Watchers

2 Comments

NativeSon

Gabriel

Although I may not agree with the FIT approach I do understand where they are coming from. They know that something is fishy about all of these “protests,” “activists” and “protestors.”

They are right because MOST of these “grass-roots” protesters are actually Cuban Communist’s and it is essential to gather intelligence on Foreign Agents. Let MI5 do it instead!

I can assure you that the “Occupy Movement” is a complete Communist fraud as 99 percent of the 99 percent are Cuban Communist’s…

Very good piece – looking forward to having this form of state control not only monitored, but deconstructed