Review: Einstein on the Beach (Barbican) Arts & Culture

Arts & Culture, Classical & Opera, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Wednesday, May 9, 2012 8:46 - 0 Comments

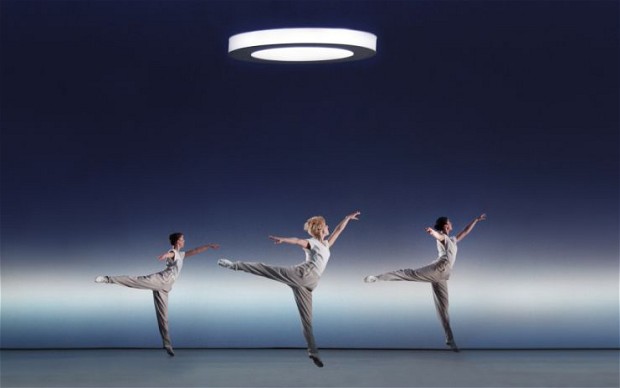

Phenomenal concentration: hats off to the performers of ‘Einstein on the Beach’ (Photo: Lucie Jansch)

Philip Glass and Robert Wilson’s impressive but demanding spectacle (for want of a better word – opera, perhaps?) had its UK premiere at The Barbican last week.

A five-hour piece of song, dance and poetry supposedly related to the life and work of the world’s most iconic scientific figure, Einstein on the Beach has no narrative and a lot of very odd imagery and symbolism. Wilson claims, “You don’t have to understand anything. It’s a work where you go and you can get lost. That’s the idea.” This is wise advice. Searching for ‘meaning’ in Einstein and attempting to make sense of just why its performers are doing what they’re doing (and they certainly do ‘it’ incredibly well) can lead you into hairy territory.

But it is hard not to. When faced with such outrageous ‘artiness’, it gives some comfort to try and attain an element of understanding. Once the questions begin, however, they do not stop. “Why does that performer wear a red shirt, when all the others wear white?” “Why was there a Native American squaw at the first Trial Scene but not the second?” “Why does that woman who keeps shouting “No” look like ‘The Lady in the Radiator’ from David Lynch’s Eraserhead?” “Hang on a minute, this whole thing is quite Lynchian at times. Is that a direct reference?” A quick wiki check reveals that Eraserhead, Lynch’s debut film, was released a year after the first production of Einstein. There goes that theory. Etcetera.

Better to “get lost”. This is far easier than working it out so you may as well. Einstein is hypnotic, it is mesmerising. As well as being musically and visually repetitive, the libretto consists of apparently random phrases, speeches and numbers said over and over again. It is at its best when it becomes almost boring, when it seems appropriate to take advantage of being allowed to leave the auditorium for a break (at five hours with no intermission, there is probably a law against stopping you). Just when you work up the nerve to go sidling out through the rows, suddenly something changes: the chorus or a new baseline come in, the harmony sequence is extended higher, or a dancer, who has been repeating the same tortuous motion for fifteen minutes adds a new gesture to their sequence. When a change like this takes place, though subtle, it seems to be on a monumental scale as it wrenches you out of the pattern: it is very beautiful, almost profound.

The choreography, by Lucinda Childs (who also wrote some of the libretto) is genius. A lot of it is deeply unsettling. The performers move like the bowler-hatted man in ‘The Ministry of Funny Walks’ but with the soul and humour taken out. They sport rictus grins for much of the show. Helga Davis, one of the featured performers of the company, has a particularly good one, both when she is about to shoot someone in the Night Train scene, and when she is enjoying a lollipop in the second Trial Scene. That the same expression is pulled for both murder and sweeties is a good example of the strange dreamworld you enter into with Einstein.

The two Dances of the show are among its most captivating scenes. As most of the production is slow, incredibly slow, slow to the point of testing one’s sanity and patience, they come as a relief. Lasting at least a good twenty minutes each, the energy and strength of the eight dancers, all in blinding white, is as impressive as their skill. They pirouette and leap backwards and forwards across the stage, creating a strict and almost simple pattern out of the chaos of their movement.

Again, you find yourself asking questions: “Chaos, pattern…doesn’t that have something to do with physics and nature?” “Do the dancers represent the electrons that whirl around the fixed point of an atom’s nucleus? Atoms, surely being relevant as this is Einstein on the Beach…” No. Best to leave it. “Get lost” in the dance until the sheer joy of their energy becomes disturbing, as any joy that is so unnaturally sustained would.

Einstein ends where it began, with the same Knee Dance that opened it. These signature Wilson interludes are not actually dances, but little scenes that connect the otherwise disparate acts of Wilson’s works: knee as in joint. After the intensity of the experience, having felt as though you’ve lived through quite a lot, a return to the opening gives almost a sense of nostalgia, or deja vu, particularly when coupled with Glass’s moving, sequential score. Character 1’s speech at both beginning and end (recited by Kate Moran, a performer notable for her unbelievably captivating voice) includes the lines ‘These are the days, my friends, these are the days’. Perhaps encouraged by the aforementioned nostalgia, this line takes on a particular significance.

This Einstein is a faithful reproduction of the original 1976 version. Despite how imaginative and daring much of the direction is, it already seems strangely outdated. You walk away with an odd, somewhat patronising feeling of “Ah yes, all that seventies experimental formalism”. Einstein on the Beach is no longer the brave new world it once was: “those were the days.” Though perhaps the fact that it feels so unoriginal at times is a testament, if nothing else, to the huge influence that both Wilson and Glass have had on theatre and music over the past three decades.

Einstein on the Beach

An opera in Four Acts by Robert Wilson and Philip Glass

4 – 13 May 2012 / 18:00, 17:30, 16:00

Barbican Theatre

Leave a Reply