“Chaos never died”: Hakim Bey’s Ontology An A to Z of Theory

Columns, In Theory, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, November 24, 2017 16:56 - 0 Comments

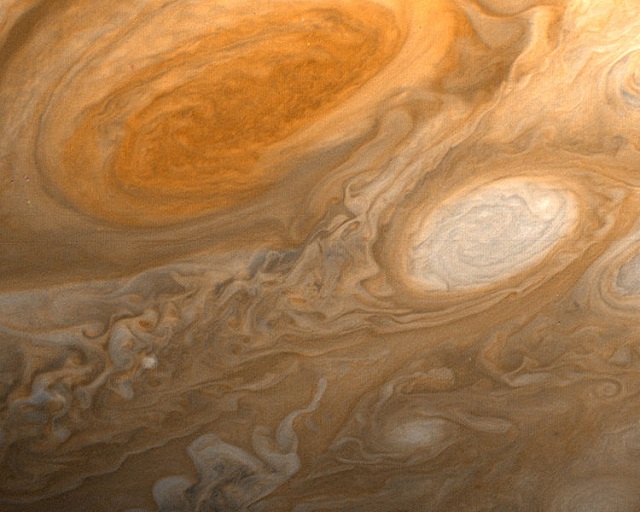

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, an example of self-organization in a complex and chaotic system. (credit: NASA)

“Chaos never died”. This is one of the best-known slogans from Hakim Bey’s seminal work, TAZ. In the second of a sixteen-part series, Andrew Robinson reconstructs the ontology of Bey’s “ontological anarchism”. He examines what it means to take chaos as ontologically primary, and how a sense of meaning or order can emerge from chaos.

Chaos Never Died

Bey’s ontology is based on the primacy of chaos. The concept of chaos should not be seen as a synonym for disorder, or an attention-grabbing rephrasing of anarchism. Chaos is not simply the absence of laws or the state. It is an ontological condition characterised by constant flux and flow, the absence of normative or other criteria of order, and a state of being akin to intoxication. Chaos, Bey tells us, is ‘continuous creation’. He also repeatedly states that ‘Chaos never died‘. Chaos has survived the supposed foundation of order. It is a basic ontological reality we should embrace and celebrate.

There are thus no essential or natural laws to provide us with meaning. Nature, says Bey, has no laws, only habits. Meaning creation is, then, a matter of personal construction based on desire. The only order possible is the order one produces and imagines through ‘existential freedom‘. All other orders are illusions. Life and the body are permeable, ad hoc, impure, and full of holes. Yet nevertheless, existential autonomy and self-actualisation must be accomplished in this field. In any case, Bey prefers a world of ‘indeterminacy, of rich ambiguity, of complex impurities’ to purist utopias. Chaos is therefore desirable as well as ontologically basic, or necessary. Bey sometimes portrays his theory in terms of a decision to say yes to life itself. In another work, Bey describes himself as a ‘bad prophet‘ who bets on unlikely anomalies and chaos.

Chaos is something prior to thought and social construction. Bey conceives Chaos as a creative potential underlying all reality. It means that living things can generate their own spontaneous orders. It also undercuts the legitimacy of all hegemonic and hierarchical systems. Bey suggests that something comes into thought which consciousness attempts to structure. The structure appears to be the foundational level, but it isn’t. This analysis rules out representation, but not thought as such. Indeed, thought and images are both important. Letters or hieroglyphs are both thoughts and images. Bey celebrates a type of in-betweenness which deals with both thought and images.

Chaos is primary over order. In fact, order is an illusion. We are always in chaos, but sometimes we fall for the lie that order exists. This lie leads to alienation. The world is real, but consciousness is also real since it has real effects. In one passage, Bey suggests that the self cannot produce things, nor be produced. Everything simply is what it is, spontaneously. In ‘The Information War’, Bey argues that information is chaos, knowledge is spontaneous ordering from chaos, and freedom is surfing the wave of that spontaneity. He counterposes this view to the gnostic dualism of those who use information (or spirit) to deny the body. Instead he seeks a ‘great complex confusion’ of body and spirit.

Access to chaos comes through altered consciousness, but chaos is also always present in everyday life, beneath the surface. Chaos, or imagination, is the basis of a field which is outside the ordinary. However, it is also the field from which the ordinary is composed. It can enter into ordinary life. Interpretation, for example, occurs in this field. It is similar to the field of becoming in Deleuzian theory, of time or the virtual for Deleuze and Bergson, and the unconscious in Jung. The numinous is ‘banal‘; it can be found everywhere. Bey refers to himself as a radical monist, in distinction from the gnostic or Manichean dualisms of the right-wing. Although he does not say so directly, he seems to treat oppressive systems as distorted forms of the field of chaos, turned aside by ‘dark magic’ or negative forms of trance. The zone of altered consciousness is also the zone of hybridity, the zone where the boundaries provided by interpretive categories break down.

Psychological liberation consists in actualising, or bringing into being, spaces where freedom actually exists. This is not something unimaginably other. Bey suggests that many of us have attended parties which have become a brief ‘republic of gratified desires’. The qualitative force of even such a brief moment is sometimes greater than the power of the state. It provides meaning, and attracts desire and intensity. Similar claims are made elsewhere in post-left anarchy. For instance, Feral Faun suggests that we all knew this kind of intensity in childhood.

Chaos as the Basis for Meaning and Order

In the field of chaos, things are held together by desire or attraction. Action is possible at this underlying, chaotic or quantum level. Magic is ‘action at a distance’. Chaos also produces a kind of order, through Eros (love) or the self-ordering activity of a Stirnerian ego. Bey adopts Fourier’s view, which he also attributes to Sufi poets, that love or attraction is the driving force of the universe. The Big Bang is ‘beautiful and loves beauty‘, although dirt is also the mirror of beauty. For instance, flowers grow from dirt.

The possibility of ‘action at a distance’ is the main belief of the Hermetic approach with which Bey identifies. This approach was supposedly banished from science in its mechanistic phase, but keeps coming back – in gravity as ‘attraction’, in quantum physics, strange attractors, the power of media, and so on (and rather differently, in Fourier’s work).

Hermeticists believed that the ‘moral power‘ of an image could be conveyed across distance, by some kind of energy beam, especially if boosted by other sensory inputs. Bey believes that artists continue to do this, even when they deny it. Advertising, for example, conveys a particular affective or ‘moral’ frame. Hermeticism thus has a dual aspect. In its positive form, it is liberatory and politically radical. However, it also provides the basis for advertising, PR and so on.

The only viable government is that of attraction or love among chaotic forces. Only desire creates values. Values arise from the turbulent, chaotic process of forming relations. Such values are based on abundance, not scarcity, and are the opposite of the dominant morality. Bey describes ‘peak experiences‘ as value-formative on an individual level. They transform everyday life and allow values to be changed or ‘revalued’. Creative powers arise from desire and imagination, and allow people to create values. Catastrophe has negative connotations today, but it originally meant a sudden change, and such a change is sometimes desirable.

Bey talks a lot about magic, spirituality, Hermeticism, esotericism, and so on. This is not ‘mystification’ in the usual sense, nor a literal belief in the kinds of magic seen in fiction. Rather, it involves reflections on the symbolic and imaginary nature of many taken-for-granted practices and objects. Something is ‘magical’ or ‘spiritual’ in a positive sense if it leads to an altered state of consciousness.

Things can also be ‘magical’ or ‘spiritual’ in enacting invisible forms of long-range communication or control. ‘Magic’ or ‘spirit’ in this sense is something immanent, something most of us have experienced already – as an intense emotional experience, romantic or sexual attraction, a psychedelic trip, a meditative state, a powerful dream, an empowering protest or direct action, a random moment where everything feels right. It does not involve reference to a transcendent field outside experience, although it is certainly taken to be outside ordinary, ‘consensus’ experience.

Bey writes as if the entities experienced in altered consciousness, or the archetypes found in dreams and stories, are real. But this is part of the process of mythically initiating the reader. The ultimate ontological status of these entities (whether they are merely imagined, or have some real existence) is not particularly important. (In a sense, if everything is chaos, oneness, or becoming, then nothing of a categorisable type is real in any case). What matters is the role of these figures, and belief in them, in producing altered consciousness and intensity.

Chaos, Religion, and Science

Bey’s idea of chaos has a number of resonances. It is similar to the idea of chaos in chaos theory, but qualitative, rather than mathematical. It has similarities with a particular style of reading quantum-level realities. It is also similar to Deleuze’s claim that becoming or difference-production is ontologically basic, and Spinoza’s univocity of being.

Bey periodically refers to Taoism, Buddhism, Sufism, Kabbalah, quantum physics, and other bodies of thought as similar to his own, although his relationship to them is often syncretic. To the extent that one understands the Tao as an undifferentiated force of becoming, it is similar to Bey’s chaos. To the extent that one understands God as immanently coextensive with being, then God is another name for chaos.

In ‘Quantum Mechanics and Chaos Theory‘, Bey argues that scientific worldviews both influence and are influenced by wider social discourses. Ptolemaic theory echoed monarchy and religion, Newtonian/Cartesian theories echoed capitalism and nationalism. Quantum theory and relativity similarly co-constitute a current social reality. However, theory continues to lag behind quantum mechanics, as scientists struggle to explain phenomena which clearly “work” scientifically. Quantum theory seems to validate Eastern and New Age worldviews, which might provide an organising myth or poetics for quantum science.

Bey summarises a series of different possible readings, some of which recover some form of realism, others of which do not. He insists that the universe must be a single reality, and suggests that the underlying chaotic nature of reality produces effects such as quantum uncertainty. This possibility could shatter ‘consensus reality’ and its claims to truth.

This could have various social effects. For example, an economy mirroring quantum theory would have to abolish work, because work is similar to classical physics in structure. The result might either be a Zerowork utopia, or a form of enslavement worse than work (probably cybernetic, and following Deleuze and Guattari’s idea of machinic enslavement).

Taoism and Buddhism are recurring points of reference. According to Wilson/Bey in Escape from the Nineteenth Century, Taoism is a Clastrian machine for warding off hierarchy, which offers direct experience in a manner similar to shamanism. Historically, it undermined Chinese Imperial mediation. In another piece, Bey calls for a ‘new theory of Taoist dialectics‘. In Taoism, Wilson argues in Shower of Stars, chaos is not a figure of evil, but full of potential. It is the source of creation. The only difference between ontological anarchism and Taoism is on the question of action versus quietism.

Bey also embraces the Zen Buddhist idea of Beginner’s Mind. In another piece, Bey compares the Buddhist concept of satori with the Situationist Revolution of Everyday Life, and the Surrealist and Dadaist concept of the eruption of the marvellous. All involve perceiving the ordinary in extraordinary ways. While Situationism neglects the spiritual aspect, Buddhism neglects the political.

Bey also likens his position to Sufism. In the Sufi tradition, a ‘single vision’ of holistic divine reality is contrasted with the ‘double vision’ of alienated consciousness. Wilson relates this to the one-eyed monsters associated with the Soma-function and with magic mushrooms, taking it to be a form of altered consciousness.

Bey’s readings are sometimes rather selective. Many of the traditions he discusses counterpose spiritual awakening to bodily pleasure. They also emphasise the channelling, constraint, or balancing of desire, not simply its release. However, Bey nonetheless traces interesting parallels among traditions of disalienation.

The idea of chaos is also similar to the primordial force which is slain by the founder of civilisation in a number of statist epics (such as the Epic of Gilgamesh). Bey further likens his view of chaos to hunter-gatherer worldviews, arguing that we need to recover shamanism against priesthood, bards against lords and so on. His approach is modelled on a language which does not yet distinguish ritual from art, religion from harmonious social life, work from play, art-objects from useful objects, and so on. In one passage, Bey depicts a war between two sets of forces. Chaos, Mother Gaia and the Titans are on the side of aimless wandering, hunter-gatherers and freedom. Zeus and the Olympians are on the side of order.

If humans are different from animals, it is because of consciousness or self-consciousness, not awareness. Animals are also aware, in a spiritual sense. However, only humans have technology – which can either be a means or can dominate us. Symbolic systems are related to consciousness. Humans are thus split between an ‘animal’ level of intimacy and unified consciousness, and a distinctly human level of alienated consciousness.

Religion stems from this tragic separation of mind and body. This, in turn, leads to a huge range of practices of ‘knowing’, ranging from psychedelic drugs to computers. But since early civilisations, religion has sought to escape the body, becoming increasingly gnostic and body-hating. Bey seeks to re-valorise the ‘animal’ level of immediate awareness.

Bey’s position on altered consciousness puts him in disagreement with many anarchists. He rejects the ‘two-dimensional scientism’ of classical anarchism. The idea of being, consciousness, or bliss contained in mystical conceptions is not for Bey a Stirnerian spook – an abstract figure to which people subordinate themselves. It is a term for a type of intense awareness or ‘valuative consciousness’ resulting from immanence, which is to say, the rejection of spooks. Techniques for higher consciousness can be appropriated by anarchists.

Bey sees science as a ‘way of thinking‘ without special ontological status. He therefore opposes the common assumption that only one type of consciousness, the scientific, has validity. One kind of consciousness – universalising, Enlightenment, linear, rational, mechanical – has dominated for too long. For Bey, experiences in altered states of consciousness have as much reality as any other kind of experience. Also, if something has effects, then it might as well be real.

Bey describes his approach as a ‘rationalism of the marvellous‘ – neither science nor religion. This rationalism accepts that some things cannot be explained. However, in Scandal, he also suggests that there is ‘something mad’ about any metaphysical experience of the oneness of being, which is chaotic and primordial. Altered consciousness is both rational (as something there are good reasons to believe in) and extra-rational (as an experience). In Sacred Drift, Bey argues that spiritual realisation is ‘good for quite a lot’, worth tasting and striving for. But it is not the end point of human development. Rather, it is a means to something deeper.

Joseph Christian Greer has explored the origins of Bey’s thought in the zine movement, and the new religious movements of Chaos Magick and Discordianism. He argues that Bey’s ontology is largely derived from these movements. He also contends that Bey’s thought is formed in debate with alternative (especially nihilistic) positions in particular zines. TAZ, he notes, is a compilation of already-published articles, which had appeared in zines such as Kaos and Mondo 2000.

The zine scene of the 1980s was rhizomatic and transgressive, often covering taboo topics. Chaos Magick and other esoteric zines overlapped constantly with those focusing on punk music, alternative sexuality, cyberculture, and radical politics. Many of Bey’s pieces appeared in the Chaos Magick zine Kaos, which operated a policy of printing everything submitted to it.

Chaos Magick is a playful religious tradition which nevertheless focuses on a central belief: that magical forces can be used to manipulate reality. It maintains, like Bey, that one can achieve ‘gnosis’ through ritual and psychedelic practices. Gnosis gives access to the forces structuring reality. Such access is normally blocked by the mass media, or other ‘psychic propaganda’.

The controversies between Bey and other contributors were focused on Bey’s insistence that the death-drive, or ‘thanatos‘, belongs exclusively to the Spectacle. Bey reads chaos as a creative force, and the role of the Chaos magician as encompassing others’ desires. This brought him into conflict with nihilistic and individualistic contributors.

In ‘The Ontological Status of Conspiracy Theory‘, Bey argues that conspiracy theory is right-wing only because it emphasises individual rather than group action as the source of social problems. Similarly, vanguardists believe the state is a conspiracy, and conspire to seize it. Alternatively, one can maintain that elites are ‘simply carried by the flow of history’. The state does not have power, so much as it usurps individuals’ power.

However, social forces do not simply determine individuals. Rather, there is also a feedback mechanism in which people modify the forces which produce them. He calls for an existentialist valuing of acting as if actions can be effective, to avoid a poverty of becoming. We have to act as if we act freely, whether we really do or not. Bey also suggests that history is chaotic, and abrupt denials of all conspiracy theories reveal an irrational faith in the superficial social world.

Chaos and Technology

For Bey, techniques and technologies are associated with ‘action at a distance’. Technology is a kind of magic. This position renders Bey both sceptical of modern technology, and hostile to the wide-ranging anti-technology positions of some eco-anarchists. For Wilson, writing in Ec(o)logues, only a type of technology which ‘enhances freedom and pleasure for all humans more-or-less equally’ can provide a basis for the flourishing of creativity and individuality.

Neolithic technology fits this definition. However, some modern technologies – such as bicycles and balloons – are basically of the Neolithic type, even though they were invented much later. Similarly, renewable energy, handlooms and the like are the right kinds of technology.

In a piece titled ‘Domestication‘, Wilson argues for Fourier’s idea of ‘horticulture’ as a system which combines aspects of agriculture and gathering. A transition to horticulture seems more viable than the anarcho-primitivist idea of a transition to hunting and gathering. Furthermore, Bey suggests that domestication was initially not control, but an effect of love (caring for a young animal). However, in another paper, Bey argues that agriculture is the only truly new technology, and amounts to ‘cutting the earth’. It instantly seems a bad deal to non-agricultural peoples, and leads to authoritarianism.

In ‘Back to 1911‘, Bey suggests that refusing technologies past a certain point can allow the recovery of imagination and ‘human life’. For example, amateur communal music is preferable to recorded music, and letters to telephones. Like many of Bey’s experimental proposals, this is a way of creating altered everyday experiences.

Bey has an ambiguous relationship to eco-anarchism. He opposes the rejection of technology of authors such as Zerzan. But he also calls for a psychological return of ‘paleolithic‘ or ‘primitive’ techniques such as shamanism. He frames this as a return in a psychoanalytic sense – a return of the repressed. The paleolithic continues to exist at an unconscious level. Bey also supports Luddite tactics against technologies used for oppression today, whatever their future potential.

But chaos implies a right to appropriate the high-tech as well as the paleolithic. Bey does not seek to reduce the level of technology, but instead to recover lost psychological or spiritual techniques. He also suggests there is a kind of future which is at once paleolithic and sci-fi, and also immediately present to those who can feel it. This future involves new technologies of the Imagination, and a new science beyond quantum science and chaos theory.

In ‘Primitives and Extropians‘, Bey responds to the appeal of his theory both to deep ecological and anarcho-primitivist approaches, and to Internet-focused and science-fiction movements, which have radically different attitudes to technology. He accuses anarcho-primitivists of a puritan impulse which uses the ‘primitive’ as a metaphysical principle (an essence, trunk, or spook).

On the other side, pro-technology ‘Extropians’ lack a critique of modern technology. They are also too purist, whereas the field of desire is ‘messy’. Zerzan criticised Bey on the back of this article for failing to understand the oppressive effects of technology. In Seduction of the Cyber Zombies, Bey suggests that there is some point at which technology flips from serving to dominating humans, and we need to keep it serving humans.

Bey calls on people to think about technology and society without absolute categories. Instead, a ‘bricolage’ or ad-hoc approach should be used. ‘Appropriate’ technology should be selected based on maximum pleasure and low cost. Bey suggests that the basic principle after the system is destroyed would be freedom from coercion of individuals or groups by others. The ‘revolutionary desire‘ of freely acting people would then arrive at the appropriate level of technology.

In terms of levels of technology, Bey suggests that it ultimately comes down to desire. Do people who want computers or spaceships really want them enough to make the components themselves? If so, they will happen, if not, they are impossible, since people will reject alienated work.

While primitivists are sure that such a situation would preclude all technology, Bey is less certain. Both sides will be reconciled to it because it is based on pleasure and surplus, not scarcity, and the process of creation and conviviality would be more immediate and human-scale.

In TAZ, Bey opposes the idea of a return to the Paleolithic or any other period. Instead, he writes of a return of the Paleolithic through shamanic practices and zero-work, a return analogous to the Freudian return of the repressed. This position is implicitly directed against anarcho-primitivism. Similarly, he rejects the primitivist position of trying to reverse the rise of agriculture.

Later, however, in Riverpeople, Bey/Wilson has come round to the view that people were ‘meant to live’ like indigenous hunter-gatherers or gardeners. This is the high stage of human development – not today’s ‘Civilisation’. Hunter-gatherers may know hunger, but not scarcity. He calls for a return to gathering, hunting, or swidden (slash-and-burn) cultivation, and the renunciation of literacy.

In Shower of Stars, Bey argues that hunter-gatherers have a way of thought based on the generosity of the material bodily principle, similar to peasant carnivals. He also argues that wilderness can be recovered. Even if it has disappeared today, it can be restored or summoned back. We need to forget (but not forgive) the system, and become radically other to it, remembering our ‘prophetic selves’ and bodies.

In Ec(o)logues, Wilson includes a ‘Neo-Pastoralist Manifesto’ which suggests inculcating superstitious fear of nature as a way to ensure it wins the ‘war on nature’ against humans. It is important that any return to nature take the form of ‘coherent actions for re-enchantment’, not passive tourism.

For the other essays in the series, please visit the In Theory column page.

Editor’s note: With regards to Hakim Bey’s controversial personal stances, these will be discussed in Part 10 of this series. In the meantime, please read our ‘Note to readers’ at the end of the introductory essay of the series.

Leave a Reply