Borders are a weapon of racism and austerity, not a solution to either Analysis

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Monday, September 12, 2016 19:21 - 1 Comment

Any progressive politics that seeks to fight class and race-based oppression needs to take up the cause of ‘the immigrant’. We need to combat austerity without summoning immigration control. When tackling racist violence on our streets, we need to recognise that racist violence is both at its sharpest and most hidden within the field of immigration control. Fighting racism should mean resisting immigration control, asWednesday’s secretive, mass deportation charter flight to Jamaica should remind us.

In the wake of Brexit, we clearly need to listen, to engage with, and to try to understand the discontent of many of those who voted Leave. But we can’t do so without first recognising that racism shapes the whole landscape in which this discontent finds voice.

In this piece, I want to argue that there can be no way forward in which we abet, let alone embrace, anti-migrant sentiment. Immigration control is a weapon of racism and austerity, not a solution to either.

Brexit and Class

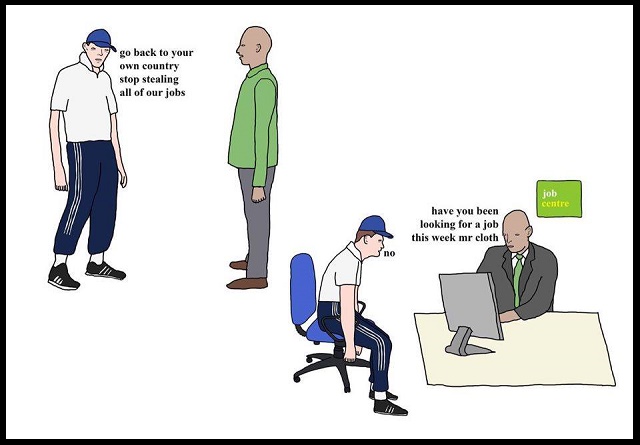

This cartoon, popular among some Remain voters during the EU referendum campaign, illustrates the Classist nature of some of the Left’s responses to Brexit (Source: @SimpsonsArt – Facebook)

The Brexit campaign mobilised some very dark social forces in Britain. These are dark (or perhaps White?) times; but much of the response from the ‘Remain’ camp was vile and classist. This is especially misplaced given that, in absolute numbers, there were far more middle and upper-class ‘Leave’ voters than working class Leave voters: Seven million working class people voted to Leave, compared to 10 million middle and upper class voters. We could equally view the referendum through the lens of age, or a metropolitan/provincial split. Or, indeed, in terms of race, given that most (65-75%) people of colour voted to remain. The notion that we voted to leave the EU because working class people took a stand seems, at the very least, questionable.

Nevertheless, it is clear that many working class people did vote to Leave; notably in deindustrialised regions of the country. Some on the Left, before and after the referendum, sought to understand why this was the case. They explored the historical context in some of the places in which the Leave campaign triumphed, and tried to provide voice and complexity to the voters themselves (for more on that, see this excellent short film).

Why we voted leave: voices from northern England from Guerrera Films on Vimeo.

Much of this commentary was insightful, but the danger comes when immigration control is understood as a kind of solution to this misery; in other words, when borders become tools of class struggle.

For example, Paul Mason, writing in the Guardian just before the referendum vote, ends up arguing that concerns about immigration are valid, both in terms of falling living standards and the ‘cultural impact’ of population influx. However, when Mason talks of strains on resources, he ought – at the very least – to offer better evidence for his argument; especially when so much of the available data suggests migrants from Eastern Europe bring net benefits to the economy, and that – as confirmed by a recent LSE report – UK workers in the areas with the largest rates of EU migration have not suffered from increased unemployment or falling wages as a result.

In other words, when things get worse, as they have for many since the financial crisis, there is scant evidence to suggest that this has anything to do with immigration.

Mason has written powerfully about the violence of austerity, and yet by suggesting that an influx of immigrants leads to falling living standards, he seems to cut his own analysis short. Austerity, Mason argues, is a choice, and we could share things more equitably, yet apparently this does not extend to immigrants. Immigrants, in Mason’s analysis, do put a real strain on the rest of ‘us’.

But who is this ‘Us’ he evokes? Who are ‘We’? Where should we draw the line demarcating ‘Us’ from those who are ‘Not Us’? Where, for instance, do Polish immigrants fit in this landscape? Those who have been here for a few years, and who have family members in Poland who might want to join them in the UK?

What about those in the former colonies? What about their histories and connections to this island? There are people who want to join their family members here, to escape the grinding poverty that neoliberal policies have wrought on their homelands? After all, joblessness, poverty and falling wages are not uniquely British problems – they are, if anything, more sharply felt elsewhere.

Is the world a better place if people just stay put?

We also need to think hard about this language of ‘cultural impact’, both in its lazy reference to ‘culture’ and in its directionality. The language of ‘impact’ problematises newcomers, rather than the ways in which they’re received. When the problem is impact, rather than racism, it is the newcomers who are subjected to scrutiny: Over their values, identities, and work habits. Racism is not the primary issue here, it seems, because its proponents were here first.

Even though Mason acknowledges the ultimate evil of neoliberalism and austerity; by failing to talk about racism, and instead employing the language of ‘cultural impact’, he reveals his solidarity to be partial. By taking up the cause of the ‘indigenous’ working class, and suggesting that immigration threatens their livelihoods, Mason ends up justifying immigration controls morally. That is, immigration control protects the forgotten and fucked-over – the members of ‘our’ community who no one cares about any more.

Of course, this is not about Paul Mason per se; I reference him because he is a strong voice on the left, but his arguments illustrate a dangerous consensus on immigration. Last month, the Labour leadership candidate Owen Smith bravely conceded that there were “too many” immigrants in “some parts” of Britain. His argument mirrored Mason’s almost exactly, and was couched in terms of a ‘benign patriotism’. He was merely speaking up on behalf of the ‘ordinary people’, against the metropolitan elite (read Corbyn). His is a pseudo-heroic posture that has become increasingly popular in Brexit Britain: in the mainstream media, in academia and among politicians. Ultimately, it is deeply nationalistic and bordering.

This is not to suggest that commentators, such as Mason, are hateful or xenophobic, far from it; only that they should better understand the discursive terrain in which they are writing. Offering brave pieces in the Guardian about how immigration really is a problem for ‘ordinary people’ in the peripheries – speaking truth to the metropolitan liberals – is not progressive. The work it does only seals the consensus on immigration, and limits the reach of anti-austerity politics by not fully challenging the perennial myth that ‘there is not enough to go around’.

While articles about forgotten, deindustrialised towns are really important, they are often based on the assumption that ‘Working Class = White and non-migrant’. Armed with this premise, the authors of such pieces invariably go on to suggest that immigration threatens the livelihoods and communities of white working class Britons (though the word ‘white’ is rarely mentioned explicitly).

It is often unclear where the evidence comes for these alarmist claims about falling living standards and devastating cultural impact. We need to remember that most anti-migrant narratives are based on generalised fear, filtered through the press, rather than on concrete experience. (It is no accident that anti-immigrant sentiment is often strongest in areas with the fewest immigrants).

So the problem is not immigration but racism. It is about reception of immigrants in discourse, rather than scarce resources and cultural tension. The fact that we are told immigrants are “taking our jobs” is more important than whether they are or not. If we believe it, then it has consequences.

Immigration control and colonial amnesia

As alluded to earlier, commentary on immigration brings the deeply political question of ‘membership’ to the surface: Who are we? How far do the bounds of our morality extend? Who counts as ‘us’?

Immigration controls always rely on first defining one group as ‘Us’. Who we are is a question that immigration controls work to settle. But we do not all relate to Britishness in the same way. For some British citizens – people who have family stories about partition in India, or who think about reparations for slavery; who worry about Lagos as much as London – the British immigration regime might be viewed as oppressive and violent. Immigration controls demonise and punish racialised British citizens, their families, and their people; they do not protect them from ‘outsiders’. Drawing the contours around the national ‘we’, demarcating “us” and “them”, is highly contested. And it has everything to do with race.

Of course, there are people of colour in the UK – including many children of migrants – who do worry about immigration. People have real fears for their futures, and are told that more people coming in will make things harder for them. Moreover, the types of migrants (e.g. asylum seekers or labour migrants, temporary or permanent), and their national and ethnic origins, are important factors affecting public opinion on the issue.

People’s views on immigration are complex and fractured – based on media narratives as well as various prejudices – and there is no automatic solidarity between non-white Britons and migrants from Poland, Afghanistan or Albania. While most people of colour voted to remain in the EU, a significant proportion voted Leave.

With many people of colour also concerned about immigration, we ought to reflect what happens when we, too, support a politics determined to reduce the number of immigrants? Are we not immigrants ourselves? Third-generation, perhaps, but immigrants all the same? We would be unwise to think that hostility towards Eastern Europeans can be neatly separated from the wider racism against non-white Britons.

One key lesson from Brexit is that with inflammatory anti-migrant politics comes racist violence. They are not disparate phenomena but symptoms of the same disease – British racism – and there is no fighting one without fighting the other. The reason immigration gains such traction as the primary threat facing ‘ordinary Britons’ is because Britain is racist. This is fundamentally related to the fact thatmost Britons don’t think colonialism was a bad thing: Because key episodes of the Imperial record, such as the Bengal Famine and the Mau Mau uprising, are not things we learn about; because Britain proudly abolished slavery, and yet won’t apologise for the untold suffering it caused, then and now.

Because “this is ‘our’ country, ‘our’ wealth, and we’ve taken as much immigration as we can handle”.

In fact, the street racists are not as marginal as we imagine them to be. The fear that Britain has changed beyond recognition, and that “we need to take our country back”, has mass appeal. It is a fear that has everything to do with immigration and race; and has been a common thread in the twentieth and twenty first century, defining Britishness, and ultimately justifying a flurry of immigration legislation over the last six decades (with Labour no less guilty than the Tories). Viewed in this context, immigration control is merely the bureaucratic, faceless, hidden set of policy responses to the very same angsts, fears, and White supremacy that motivate the street racist. If this is true, then anyone who is concerned about racist violence should be equally concerned with immigration control – especially contemporary immigration controls, which are unprecedented in their reach, intensity and violence.

(See this documentary).

Everyday Borders from CMRB on Vimeo.

Put simply, as long as we don’t acknowledge how deeply racist Britain is – and imagine that we can justify, morally, the immigration controls enforced in our name to protect ‘us’ from ‘them’– we won’t be able to build a meaningfully progressive future for all.

What happens when we reach for immigration control?

In today’s Britain, policy dictates that immigrants should not have access to free healthcare, should not be able to move jobs, should not claim benefits, or have access to legal aid and appeal rights. We would be naïve to think that this is just about immigration. This is about the erosion of all of our rights and the violent imposition of neoliberalism.

When certain categories of asylum seekers receive meagre benefits on a voucher card, which can only be used in major supermarkets, we should worry about the precedent for all welfare claimants. When we demand an Australian-style points system – drawing fit, wealthy, qualified migrants to the UK, and locking the rest out – we should question how this relates to sweeping cuts to disability benefits and income support. When undocumented migrant women are being billed £6,000 for a normal birth, we should fear for the future of the NHS. When landlords must now check the ‘right to rent’ of all tenants – to weed out undeserving, disentitled immigrants – we should think about the more general erosion of our rights to decent, affordable housing.

If we can only wake-up to the dangers of immigration controls through the damaging precedent it might set for the rest of ‘us’, so be it. There is truth to the ‘first they came for the immigrants’ kind of prognosis. But we should think more broadly about what borders do: whether in the Mediterranean, in the spectacular border games at Europe’s edges, or even in the banal visa policies that prevent people seeking futures elsewhere.

Borders kill, let die, and immiserate. Any progressive politics must seek to dismantle them.

So where does this leave us? I am not expecting that we will abolish all immigration controls any time soon, but let us at least begin think about what they do and what they represent. Guardian columnists might not support the contemporary immigration regime, but they legitimate it every time they portray immigration control as a solution to austerity, rather than a driver of it.

We need to join the dots between the remarkable acts of racist violence on our streets in recent weeks, and the unremarkable – indeed, invisible – acts of violence enacted through immigration controls. For as long as we concede that immigration controls are legitimate, and have nothing to do with race, we allow for colonial amnesia to go unchallenged. Every time we problematise immigration, we play into the hostile, racist environment that has seen a spike in violent attacks. And when we decide to take up the cause of working class white Britons, who have been forgotten and brutalised in austerity Britain, let us not allow our class politics to justify and abet immigration controls.

As we work out how to move forward in the wake of Brexit, we need to understand what immigration controls do, and the politics they represent. Sipping from ‘Controls on Immigration’ mugs cannot be the position of anyone concerned about racism, inequality and austerity. Challenging the consensus on immigration control is the only way to build progressive futures for all of us.

1 Comment

Ivan Hansen

Hint, your article is too damn long