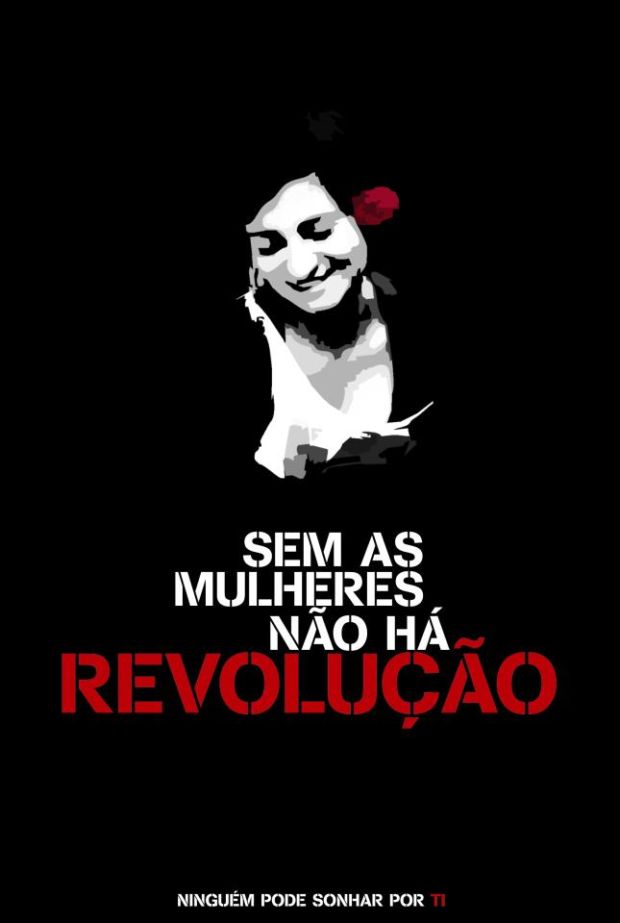

The Tide is Turning: from the Feminisation of Poverty to the Feminisation of Resistance Beautiful Transgressions

Beautiful Transgressions, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Saturday, December 31, 2011 9:00 - 0 Comments

By Sara Motta

The year is about to turn and with it the tide is also turning. Mothers, who are often the poorest of the poor, are no longer merely victims of the market logic of competition, division and austerity but are fighting back. As we argue in the editorial of the most recent edition of Interface, Feminism, Women’s Movements and Women in Movement, the feminisation of poverty is becoming a feminisation of resistance, particularly in the Global South. What lessons can we learn here from these struggles?

The year is about to turn and with it the tide is also turning. Mothers, who are often the poorest of the poor, are no longer merely victims of the market logic of competition, division and austerity but are fighting back. As we argue in the editorial of the most recent edition of Interface, Feminism, Women’s Movements and Women in Movement, the feminisation of poverty is becoming a feminisation of resistance, particularly in the Global South. What lessons can we learn here from these struggles?

Mothers who are heads of households are one of the groups (including young people) that are the hardest hit by the austerity measures and economic downturn in the UK. As Howard Reed, for the Fabian Review argues, the government’s programme of public spending cuts is having a disproportionate effect on women. Cutbacks to benefits, tax credits and other subsidies affect women severely, particularly working mothers. The removal of state services privatises reproductive labour onto the family, hence often onto the shoulders of women, who are still predominantly those that carry out domestic labour. As Emilia Hill recently argued in the Guardian, hard won victories for women’s equality are being eroded.

Women are often employed in unregulated and precarious working conditions, on temporary contracts with little or no rights to maternity leave, sick pay and protections against sexual harassment. As a recent TUC report demonstrates, these are the first economic sectors to be hit by cuts and as they are feminised it is women who are hit the most severely. Yet these women still have to ensure that their children eat, have a roof over their heads, clothes, schooling, health, love and nurture. What can be learnt from women of the Global South?

Women in the global south (and sections of the global north) have experienced the dislocations, violences and exclusions of market logics for decades. The removal of public provision of health, education and housing reinforces the care responsibilities of women. Economic crisis and cuts backs increase unemployment undercutting the survival mechanisms of poor families. Taken together they result in the breakdown of community solidarities, social bonds and collectivity (a similar story to the story of austerity and marketisation in the UK).

Yet they are not only victims of these processes, as women never are. At the heart of the community and the family they have been at the heart of resisting these processes by organising the collective provision of housing, education, health and childcare.

In the process, the meaning and practice of motherhood and womanhood become a place of political struggle.

No longer is motherhood confined to the individual care of partner and children. Instead motherhood becomes a symbol of collective community caring and nurturing. Women’s knowledges are combined and reclaimed as the basis of creating sustainable systems of food production, health care, community education and housing.

Many food co-operatives collectively organise the production, distribution and consumption process with community need as opposed to profit the ethic that underlies the entire process. Through this they attempt to ensure a sustainable use of land and resources and the distribution of food to ensure everyone’s survival. This ruptures the logic of competition, individualism and consumerism that rips communities apart.

Education projects organised with popular education methodologies are widespread. These build upon participants’ life experiences which are engaged with as sources of knowledge and understanding. This involves a recovery and reconstruction of cultural traditions of dance, song, and music and local knowledges about the geography of place and traditions of healing and herbal lore. Education is not viewed as a means to an end (of becoming an exploitable and docile worker) but rather as a path of empowerment and liberation through collective thought and action.

Property and land have often been privatised or sold off, displacing rural communities and excluding poor communities from a right to be a part of the city they live in and the right to have a decent home. Women and family-led movements are taking back land, buildings and the city by occupying and reclaiming space for the community. An inspiring, poor people-led community organisation in the United States is Poor Magazine.

Education projects and food–cooperatives, as well as a plethora of other projects are organised in these spaces. The occupation of space in this way recreates community by transforming relationships of strangers characteristic of austerity to relationships of friendship and solidarity characteristic of resistance. This opens up possibilities for poor women and their families to live decent and dignified lives.

As part of these struggles no longer is womenhood confined to a role in the private sphere as mother, daughter or wife or to an unregulated market sphere of super-exploitation. Rather women take centre stage in the struggles for recognition of their community and family’s right to a dignified life determined on their own terms. Women become the thinkers, facilitators and organisers in their communities.

As Mariela, community organiser from the Comités de Tierra Urbana (Urban Land Committees) in the shanty towns of Caracas recounted to me, ‘We worked with our community building solidarity and attempting to encourage reflection about the problems that we faced. We developed the programme of democratising the city, built on the idea of democratic control over our environments in order to create social justice for all, with access to, and control over, education, health, employment, community.’

Women are at the heart of the discussion, experiments and practices of creating the institutions, processes and ideas to construct such a dignified life.

Such politics impacts upon how women’s bodies are experienced and lived. Women have been at the forefront of struggles against marketisation and injustice- central figures in the uprisings of the Arab Spring, in protests against cuts across Latin America, in campaigns against the privatisation of water in South Africa- reclaiming both public space and the space of community as a site of collectivity, dignity and power.

This challenges the female body’s exploitation, objectification and commodified sexualisation. The body is not merely a site of pain, pleasure for others and exhaustion but is also an embodiment of the ability to create and defend life. Women who stand against the coercion and violence of the state in protest, women who sing and use their voices to bear witness to the violence of marketisation turn their bodies into sites of resistance and pride.

These practices re-make and re-invent broken solidarities, social bonds and collectivity. In the logic of their resistance is a reimagining of the political; away from the dominant script of power politics around great leaders, parties, the winning of elections and the occupying of the state towards a politics of everyday life, social relationships and self

Yet this politicisation is not tension free. Women now often carry a triple burden of paid, domestic and political work. Women are organisers in the community yet often still subject to oppressive and gendered power relationships in the private sphere. Women’s participation in movements is characterised simultaneously by inclusion and marginalisation.

However, the implications of the feminisation of resistance are far-reaching. It challenges traditions of western political thought ( reformist and revolutionary), resting as these do on a masculinist conceptualisation of the political that excludes or subordinates women, femininity, the private sphere and the body.

Such resistances compel us to stretch our understanding of what politics is, where is occurs, and what is stands for. It suggests that a reimagining of a liberatory politics and theory for our times must take women’s resistances seriously. Dialogue and solidarity between women in the Global South and Global North is an essential part of this process.

No longer can we allow the feminisation of resistance and women’s struggles to be at the margins of scholarly and political debate. Their energy, creativity and knowledges are breaking through the cracks of our bankrupt system of politics as normal. It is time we all took notice.

To read more about the feminisation of resistance see Interface: a journal for and about social movements, current edition, Feminism, Women in Movement and Women’s Movements http://www.interfacejournal.net/ of which Sara Motta is one of the co-editors.

Leave a Reply