Beautiful Transgressions The Politics of the Female Face

Beautiful Transgressions, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Tuesday, May 3, 2011 0:00 - 7 Comments

By Sara Motta

On St George’s Day we were walking in central Nottingham as it started to spit with rain. I placed a scarf around my head and face to protect me from getting wet.

The English Defence League (EDL) had organised a flash mob earlier. A white man with a St George t-shirt began to stare at me with hatred in his eyes. Two days before I had been in a discussion with a ‘liberal’ friend about the banning of the burqa in France. He had been in favour of the ban there and extending it to the UK, arguing that a woman covering her face was an assault to his right to communicate and that ‘we’ British felt excluded by such cultural traditions.

The discourse of ‘othering’ underlying such everyday interactions and discussions involve at its worst an absolute ‘othering’ and de-humanising of women identified as Islamic. Other arguments assume that Islamic women that choose to cover their faces are removing themselves from civilised communication in which ‘we’ (often men) have a right to see a woman’s body and face. It is argued that this act of covering is a form of de-subjectification and a result of oppression. In all cases the political agency and experiences of these women is denied.

One of the most pressing political problematics we are facing in the UK is how this discourse is internalised in everyday desires, understandings and behaviours. Increasing social and economic exclusion is happening in the context of communities broken by the multiple violences of neoliberalism. Many people feel powerless, alienated and betrayed by political elites. The finding of someone to blame for such loss creates a fertile terrain for this discourse of othering to flourish.

Whilst produced by elites it works as a mechanism that pits community against community, race against race and woman against woman. It justifies further interventions by the big brother state into our everyday lives; a state that is implicated in the very violence that has shattered and excluded so many communities.

We must develop ways to connect with people’s legitimate feelings of betrayal, alienation and loss to open up dialogue and lead to different inter-subjective, social and political interactions. A way to do this is to disrupt the simplistic assumptions upon which the discourse of ‘othering’ of Islamic women’s choice to wear a niqāb is premised.

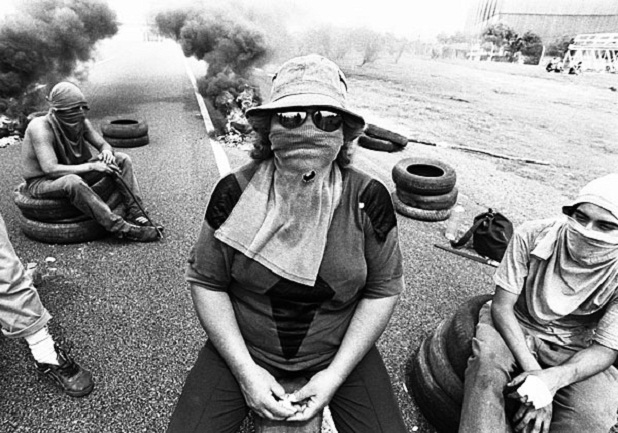

Here, I hope to contribute to this disruption and open up a dialogue by sharing some of the experiences of the Argentine piqueteras (female members of the unemployed movement) of the Movimiento de Trabajadores Desocupados de Solano (MTD Solano) who often cover their faces in public actions.

In the late 1980s Argentina undertook one of the most radical neoliberal reform processes in the region with full-scale privatisation, deregulation, liberalisation and reductions in public expenditure in health, housing and education. Whilst held up by the IMF as a model of reform it was enabled by policies that actively disorganised and silenced popular politics and participation. It resulted in de-industrialisation, unemployment and rapid increases in poverty and inequality.

For much of the 1990s these dynamics were masked by a credit boom. Suddenly people had access to credit to buy washing machines, microwaves and computers. Social relations and self-actualisation were measured by one’s acquisition of material goods and money. Advertising conglomerates represented the ideals of womanhood and beauty through an ever increasing objectification and sexualisation of women’s minds and bodies.

Relationships built on solidarity, mutual care and histories of political struggle were replaced by relationships based on competition, control and individualism. In many ways the multiple violences that neoliberalism wrought in the UK were mirrored in Argentina.

This appearance of calm and depoliticisation was ruptured by the uprising in response to financial meltdown in 2001.

Those excluded from this market miracle joined together to say ‘que se vayan todos’ (out with them all). Behind such a mass outpouring of discontent could be found a reinvention of politics. This challenged and attempted to transform individualised, hierarchical and instrumental social relationships into forms of living, loving and working based on democracy, autonomy, dignity and social justice. The MTD Solano are paradigmatic of such a politics.

The media and political elites represent such groups as a violent uncivil underclass that doesn’t represent the civil democratic majority. They are known for their use of the piquete- the blocking of roads to disrupt the smooth flow of the economy- as a means to make demands on the state. The Piquete is experienced as a place of freedom. As the MTD Solano explains, ‘…it’s a liberated zone, the only place where the cops won’t treat you like trash. There the cops say to you, “pardon me, we come to negotiate”. That same policeman would beat you to death if he saw you alone on the street’

The majority of members of the MTD Solano are women, often mothers, fighting for the dignity of their children, families and communities. In their thirties and forties they are at the head of piquetes wearing masks and standing behind burning tires. Such women are presented as delinquent, uneducated and unfit mothers. Yet as they argue one of the reasons for wearing a mask is because there is no space for them in political society as they face the coercive power of police and security forces, the de-legitimising discourse of political and media elites and the use of sexual violence to intimidate and silence them. They thus cover their faces to be seen and heard politically.

It is argued that the piqueteras tactics are an attack on democracy. Yet for these women the wearing of the mask has a much deeper significance. It embodies a rejection of the sexualisation and objectification of women and a politics revolving around the marketing and selling of great leaders. To cover their faces is an act of defiance against this.

The piqueteras build spaces in which there are no great leaders speaking, acting and thinking on behalf of the majority. Planning a piquete is organised using procedures of direct democracy and consensus decision-making. As Neka, participant in the MTD Solano, explains ‘We don’t need anyone speaking on our behalf; we can all be voices and express every single thing. They’re our problems and it’s our decisions to solve’. The wearing of masks, as a part of this process, is an egalitarian practice of breaking down hierarchies and relationships of power.

Piqueteras are often represented as the epitome of ignorance, conservatism and irresponsibility. Central to their practice is turning these representations on their head. The Piqueteras presence on the piquete ruptures this discourse of victimhood.

The wearing of masks is a re-articulation of political subjectivity that challenges the limits and norms of an elitist, exclusionary and commodified liberal democracy.

Through covering their faces the piqueteras are attempting through anonymity to re-construct political community and subjectivity. Such re-construction of democracy and politics happens both during piquetes but also in the building of non-commodified social relationships in their community around collective childcare, popular education and co-operative production.

This also involves a politics of effect (or politica afectiva) in which family, womanhood, love, solidarity and community are re-imagined beyond relationships based on competition, hierarchy and inequality. As they argue, ‘We do have a political project…our goal is the complete formation of the person in every possible sense’.

The discourse of ‘othering’ of the piqueteras who cover their faces shares many similarities with the discourse of ‘othering’ of Islamic women in the UK. Exploring the reasons, experiences and political agency of the piqueteras breaks down simplistic representations that present them as uncivil, uneducated and detrimental to democratic communication.

Anonymity in this case is a way of gaining voice in a political context in which there is no space for their political agency and subjectivity. Anonymity is a way of rejecting hierarchical, competitive and commodified forms of communication and subjectification. Anonymity acts as a way to open the possibilities of creating a new politics based on dignity, respect, social justice and inclusion.

This suggests that the political decision of a woman to cover her face is a complex, multi-layered act embedded in political agency, rationality and experience. Before judging the niqāb we need to listen, to ask and to speak to the women who wear it. This will help us to look beyond and behind the gaze of commodification and objectification and towards the building of relationships of mutuality, understanding and solidarity.

Masks and veils have a multiplicity of meanings and can be understood as expressions of agency and political subjectivity which challenge elitist, exclusionary and commodified liberal politics.

Sara Motta is a mother, radical educator and writer.

7 Comments

JL

Dan

Great article, which illustrates how what we do with our bodies relates to politics in complex ways.

I don’t agree with governments that make wearing the niqab/burqa compulsory, and I don’t agree with governments that forbid the wearing of it. It should be the woman’s choice.

As for the covering of the face being an assault on the “liberal” guy’s right to communicate, I have personally communicated with women wearing the niqab/burqa and, while sometimes feeling a little uneasy due to not knowing whether someone is smiling or not, it is easy enough to communicate. If I feel uneasy it is my problem and I’m quite able to deal with it!

Should covering the face actually be thought of as being so different to covering other parts of the body? I might find it more difficult communicating with a naked person in the street than a person in a burka! Just a thought

Andy

Response to JL:

It’s clear from the article that Argentina is not experienced as a liberal-democracy by the piqueteros, to the extent that they experience a risk of being beaten up by police if seen out alone – this is just the sort of thing which isn’t supposed to happen in a liberal-democracy. Britain has very similar problems, though they’re often concealed – police impunity, illiberal laws incompatible with liberal-democracy (“terror” laws, ASBOs and so on), the virtual nonexistence of the right to protest, the right to strike and several other basic rights… So framing social movements as pro or anti “democracy” is completely missing the point: it’s about being anti the actually existing dominant system which is anything but liberal-democratic. A lot of aspects of the present system are undemocratic, and in very deep and fundamental ways (not just little anomalies here or there). For instance, the police (with support from the judiciary) pick and choose what counts as ‘harassment’, ‘disorderly’, ‘anti-social’ and so on – this destroys the so-called ‘rule of law’, because these terms can be redefined as ‘rule of men’, to mean whatever the power-holder on the spot wants them to mean. And fair-weather liberals permit the violation of basic liberties whenever it’s convenient, often for the protection of other entitlements which are certainly not ‘basic’.

Liberal democracy is not an “order”, with an inside and outside, so much as a balance of forces. It depends on the separation of state and society. Too much statism, nationalism or social conservatism and it is destroyed from within – society stops being autonomous enough to externally constrain the state. (‘Too little’ and it fuses into direct self-rule, which liberals declare not so much undesirable as impossible).

I’ve never understood why people take ‘the government always getting its way’ or even ‘whatever the majority wants, it gets’ (let alone ‘the corporations or the police always winning if the government backs them’) to be ‘democratic’. Democracy is about how the government is selected, not how much power it has. ‘Democracy’ is about how the state is composed, not how much power it has. ‘Democratic’ is applied even when referring to small associations with very limited power – an organisation doesn’t stop being ‘democratic’ because its power is limited. And ‘liberal’ democracy implies that the state is very much constrained in how it can intervene in society. It’s a case of Brecht’s old saying that if the government is dissatisfied with the people, it can always elect a new people. Nationalist states seek to ‘elect a people’ by determining ways of life, but this prevents their simultaneously claiming to represent a people constituted externally – they come to represent themselves, in a circular way – at most, elections determine if they’ve succeeded or failed to manipulate people. There is also the problem that democracy applies within a preconstituted community; it doesn’t say anything about whether the power of this community, relative to other loci of attachment or other communities, is justified. ‘Democracy’ is too often getting mixed-up with nationalism, the belief in the primacy of the nation-state over other attachments. There is a fundamental hypocrisy as well, in that nobody in the mainstream is saying that it’s ‘undemocratic’ that elected governments get constrained by transnational capital, by the investment decisions of companies, or by the operation of markets. Why, then, is it ‘undemocratic’ if they get constrained by direct action, mass unrest, or strikes? If it is defined as ‘undemocratic’ for any locus outside the state to have power, then corporate power precludes democracy in any case.

It’s not possible to have an intolerant or ‘muscular’ liberal-democracy for the simple reason that it’s too statist, too nationalist – it becomes a nationalist regime instead of a liberal-democracy. On the other hand, it should be logically possible to have liberal-democracy with or without capitalism, with or without police, and so on. So resisting these institutions – which in many ways are inherently undemocratic themselves – is never ‘undemocratic’; it simply alters the field of forces within which democracy operates. The moment one goes down the path of insisting that liberal-democracy requires that society be a certain way, and the state should ensure that society is this way, one is beyond liberal-democracy since one no longer has the state-society separation; the system becomes circular – the state ‘selects its own voters’ and thereby becomes undemocratic. Too often nowadays, we hear ‘democracy’ being used as a euphemism for nationalism, or for total state power over society.

It’s pretty obvious that a liberal-democracy can’t pick and choose how people dress, for several reasons: it violates the autonomy of society; it violates basic liberties (e.g. freedom of expression and of conscience); it fails to be neutral between conceptions (imposes a comprehensive doctrine, in Rawls’s language); it imposes vulnerability to state power as an obligation, hence distorting the balance of forces against society and exceeding the state’s role by proactively moulding society to be ‘governable’; it constitutes an aggressive exercise of social power against out-groups who are effectively placed outside the community (rendering democracy within the community irrelevant to their position); etc. Issues with hoteliers and abortionists are rather different, to the extent that these are people providing public services who are discriminating in their provision. The abortion case admittedly has a certain conscientious dynamic, but I don’t see how the hotelier is acting differently from a racist who refuses to let a room to black people. How someone dresses, on the other hand, is just a matter personal action – the state seeks to control it because the state (or dominant groups) want to impose a particular way of being, a ‘comprehensive doctrine’ as Rawls would put it (in this case, nationalism dressed up as liberalism). It’s not a complicated/contentious issue with two valid sides; for a liberal (as for a radical), it’s a very straightforward issue. It’s a contentious issue today because there are a lot of states which have become authoritarian nationalist regimes in practice, but claim to be liberal-democracies. It’s an effect of the nationalist corrosion of democracy and the fruits of the Trilateral Commission, neo-fascist parties, and the tabloids.

JL

Response to Andy:

I think you`re offering a fairly romantic and certainly highly Eurocentric idea of liberalism and liberal democracy here. Maybe you`re seeking to separate some of the more lofty rhetoric that some times passes for liberalism`s soul from the reality of actually existing liberal democracy as a historical social form, but I think this is not as easily achieved as you suggest. Where is this idealised “liberal democracy” in which the state respectfully keeps a discrete distance from society? When did liberal democracy not involve police violence or attacks on the right to strike, or institutionalised racism, or constraining transnational capital, or clientelism, or imperialism & genocide etc? Its not the high theory of Locke and Rawls that the Piqueteras and the Islamic Women are subverting/resisting its the concrete practice of Menemismo/Kirchnerismo and Blairism, its not that “they aren’t experiencing liberal democracy” as liberal democracy, its precisely the opposite, that they are experiencing liberal democracy as liberal democracy, and they don’t much care for it, they want something else (broadly speaking, Popular Democracy in the case of MTD and a Sharia inspired (or atleast post-secular) social form in the case of the Islamic women).

Yes you`re right to say that the liberal-democratic state has to protect the “autonomy” of society, but you`re misinterpreting the meaning of autonomy in this context. In a liberal democracy autonomy means the autonomy to act as liberal individuals in a liberal civil society, the moment you begin to subvert and threaten that, if you`re not strong enough to defend yourselves you`ll be crushed (as has happened with the Trade Union movement in Britain, as has happened with the Piquetera/o`s in Argentina). In my veiw this doesn’t contradict liberal-democratic theory at all, liberal-democratic theory might be a bit more sheepish about it than liberal-democratic practice is, but the reality is that for both in the final instance the role of the liberal-democratic state is not to empty itself as you and some starry eyed neoliberals imply, its role is to make liberalism work upon its own terms. Does this contradict “democracy”? in some circumstances yes, but thats why its called “liberal democracy”, its only democracy within the prescribed limits of liberalism. So this is why I think you`re wrong to suggest that banning certain forms of clothing is by definition un-liberal democratic, if certain forms of clothing are perceived as subversive of liberal-democracy then the liberal-democratic state may well choose to act (I think Britain banned brown shirts as “political clothing” in the 1930s, could be wrong about that though). The contradiction is right there in your own argument you say banning a form of clothing is “impossible” because it “violates freedom of conscience” but then you imply that abortionists and hoteliers should not have freedom of conscience, to the extent that theyre more-or-less reduced to disembodied market actors involved in the “provision of a service to the public” (this is classic Thatcherite language btw). You generously concede abortion has a “certain conscientious dynamic” (which would seem somewhat mild, to those of us who perceive abortion as at least quasi-genocidal), and I agree that the issue of homosexuality is clearly less powerful (as it has no obvious innocent victim) but even so the issue of the suppression of the freedom of conscience to the extent that it comes into contradiction with the individualised logics of liberal democracy, is clearly not “impossible” as you initially suggested, on the contrary its inherent.

The final result of this romanticisation is that you end up white-washing liberalism and blaming all the ills of liberal democracy on the bogeymen of “nationalism” and a psychologised “authoritarianism”. Apart from anything else this understanding is clearly extremely Eurocentric, as soon as we look slightly beneath the surface of the “golden age” of 19th century liberalism we discover it wasn’t subverted by “nationalism” and “authoritarianism” in the form of the brute violence in the colonies, the brute violence in the colonies was absolutely constitutive of liberalism and indeed so it continues, never has liberal democracy operated in the gentlemanly fashion that you romantically imagine, its always been about resistance, repression and suppression, you just have to be willing to look beyond liberal text-books and elitist history. The implications of this elitist/Eurocentric perspective from above is a totally patronising denial of the radicalism of the Piqueteras and the Islamic Women (“How someone dresses is JUST a matter of personal action”!!!!) which situates these incredibly brave women merely as sub-cultures who should (in line with liberal multi-cultural orthodoxy) be free to practice their culturalised difference as charming instances of exotica, rather than understanding their praxis as political – as subaltern agents acting at the cutting edge of the contradictions inherent in liberal democracy.

Andy

No need for the aggressive rhetoric, I’ve just got a different analysis from you. I’m not even defending liberalism. To be honest, you gave the impression of being some kind of liberal, arguing that liberals are quite right to ban masks, and trying to justify it by spurious analogies to unrelated issues. I see liberals who do this as bad liberals (and there’s plenty of them about). I’m not a liberal but we can’t just give up on arguing with liberals about what their own ideology means. Ultimately they ARE inconsistent, they DO condone things which go against their ideology strictly speaking, and this is something which needs showing so as to 1) convince them their ideology doesn’t work and/or 2) expose them as hypocrites.

In any case, I don’t think liberalism has historically worked the way you assume (i.e. the way it works today). Nineteenth century liberalism really did insist on civil liberties for the layer of people who were recognised as citizens, i.e. bourgeois and petty-bourgeois in the global North. It maintained a colonial and class underside via exclusions from the category of ‘people who count’. But it never pretended that (for example) British-occupied India was a liberal-democracy, in the way that modern imperialism pretends that Iraq is a democracy. When Marx pointed out that British liberalism had this underside, it was still a subversive revelation because the underside really was a dirty secret. Today, nobody pretends that torture, pre-emptive raids or racial profiling isn’t happening – they try to excuse such things. Hence the situation is quite different. People manage to hold in their heads simultaneously the belief that the regime is liberal and the awareness that it does illiberal things (as Marcuse clearly shows).

Liberalism for most of its history has been a legitimating ideology of capitalism (before that, it was a revolutionary ideology, as in Paine’s work for example). Marx does not at all see bourgeois states as ‘really’ liberal-democracies – he treats liberalism as an ideology which the bourgeois state endorses in principle but violates in the small-print (see especially his discussion in the Eighteenth Brumaire of the French constitution). Nevertheless, a legitimatory ideology allows some things and disallows others. Liberal ideology has never permitted states to ban ideas, writings, clothing and so on, simply for being illiberal or subversive of liberalism. Ostensibly liberal states have always been prone to ban things they don’t like, but they’ve always been criticised as illiberal for it. In other words, it clashes with their legitimatory ideology when they do it. I would view, say, NCCL or Amnesty or ACLU circa 1975 as epitomes of liberalism as I understand it. You will see that back then (to a limited extent still today), they condemned a lot of the racism, police abuse and so on, even in liberal states of the era (e.g. the treatment of the Baader-Meinhof prisoners in Germany) – and even now, they’re not exactly comfortable with the more blatant of the abuses. You seem to want to instead say that whatever a state which calls itself liberal does, counts as liberal. I’m sure you wouldn’t want the actions of Stalin or Pol Pot used as test-cases of what Marxism involves or allows, so it’s unfair to do the same thing with liberalism.

An account of liberalism is bound to be Eurocentric, because liberalism has never been a major legitimatory ideology outside Europe (Kirschner for example is a neo-Peronist, not a liberal). However, the patterns of discourse Ashis Nandy discusses in Indian politics broadly fit with how I’m reading liberalism – the “state-as-arbiter” would be liberalism, the “state-as-protector” would be nationalism. Nandy analyses changes in Indian politics partly through the decline of the former and the expansion of the latter.

The terminology about ‘service providers’ and ‘personal action’ is of course using liberal terms, since I’m explicating how liberalism operates. You claimed that liberalism requires the banning of forms of dress which ‘subvert’ liberal-democracy; I showed how this is clearly not true, and liberal states which do such things are violating their own legitimating ideology if they claim to be liberal (in fact, most of them have covertly switched from liberalism to nationalism). This doesn’t imply any endorsement of liberal theory, I’m just showing that it doesn’t mean what you think it means.

Incidentally, Muslims opposed to headwear bans DO use a liberal language of rights and equality in making their case (see http://www.ihrc.org.uk/activities/press-releases/9212-press-release-france-partial-burka-ban-further-evidence-of-french-state-racism-concerns-that-levels-of-anti-muslim-hatred-will-rise-still-further) so it is not at all accurate to say that they portray themselves as fighting against liberal-democracy. Furthermore, the observation that liberalism has turned into nationalism in the popular mind, and thereby become reactionary, originally comes from Gramsci. So you can stop hunting for closet neoliberals.

JL

Apologies if the response came across as aggressive rhetoric, that wasn’t my intention.

So, you`re suggesting that 19th century liberalism can be distinguished from contemporary liberalism, and that 19th century liberalism represents authentic liberalism, while contemporary ”bad” liberals “go against their ideology strictly speaking”. But isn’t this a bit of a simplification, clearly liberalism has changed in response to precisely the types of struggles by the excluded that Marx and others identified, and once incorporated those invisible undersides have led to transformations in liberal theory. But recognising and visibilising certain processes doesn’t mean that they weren`t previously assumed, in particular I believe the use of coercion in the formation of a privileged individualised subjectivity in the bourgeois public sphere has always been absolutely assumed as constitutive in liberal theory. The point now is that as liberal democracy has been challenged from below / outside, there has been a much greater theoretical and public recognition of the role of the liberal-democratic state as a primary agent of the individualisation of all subjectivities, but I don’t agree that this innovation represents an essential contradiction or betrayal of early liberal theory I see it more as a theoretical recognition of what was always a practical reality. This links to your point that liberalism is a legitimatory tradition of thought, but its for precisely this reason that I don’t think you can abstract a pure liberal theory as authentic from its relation to the social processes which it is seeking to legitimise. In this context my sense is that most liberals today don’t see the state acting to protect liberalism as contradicting liberal principle, they recognise it as a necessity, so I don’t really see how an appeal to some of the classical social ideals in liberal theory has much traction. This is the point I was trying to make, its not that liberal democracy isn’t being experienced as liberal democracy, it is precisely the absolute essence of liberal democracy as the individualisation of subjectivities that is being experienced and resisted in the cases discussed.

On the point about Eurocentrism, I wasn’t suggesting that your argument was Eurocentric because liberalism hadn’t existed outside Europe (Id dispute the point here btw, surely the 19th century liberal republics throughout the Americas were in many cases even more committed to a certain idea of liberalism than their European counter-parts, at least in principle), but that the conception of liberal democracy you set out, in a very fundamental way could not have existed in Europe, without the violence and exploitation in the colonies, then as now. The nationalism and authoritarianism you suggest are corrosive of liberal democracy have always been a crucial part of liberal democracy, most obviously in ongoing primitive accumulation and restrictions on the free movement of labour. Again this goes back to the point, just because these processes were previously invisibilised doesn’t mean they weren`t assumed and constitutive, and so once they become recognised there couldn`t be patching up innovations in response.

You`re final point about Gramsci is intriguing, im not familiar with that argument, Id be interested when and where Gramsci perceives this transition from liberalism to nationalism occurring and what exactly he understands with these terms.

Finally, yep sure some Muslim Women appeal to liberal principles in defence of their right to dress as they choose (others don’t) but that doesn’t mean that at a more abstract level their action isn’t expressive of struggles over and against liberalism. To give an example, during the Iranian Revolution, young middle class Tehrani girls embraced hijab in part as a gesture of solidarity with their working class sisters, it was an expression of collective feminine identity against the authoritarian (“modernising”) liberalism of the Shah. It seems to me highly unlikely that there isn’t at least an element of this political motivation in Europe today, especially for younger Islamic women who are taking up the niqab having experienced the racism, discrimination, imperialist violence and objectification of women which is part and parcel of secular liberalism. We should remember that the Islamic rationale for hijab is to identify oneself as part of a community in solidarity against lustful practices which are sinful and lead to the violation of women by men. Of course there are elements of patriarchy here (and arguments over what exactly constitutes hijab), but its also an assertion of a collective identity (Islamic community) against the individualised secular logics of liberalism. Its very complex of course but again I think you`re suggestion that these praxes are entirely compatible with liberal democratic theory does great violence to the struggles involved and does suggest a romantic and Eurocentric idealisation of liberalism.

Andy

Ideologies have more to them than simply obscuring realities. In a functioning ideology, adherents really believe, and act on, the version of reality the ideology posits. Althusser even suggests than an ideology is a way of relating to realities rather than of seeing them. I think you’re seeing liberalism as it is seen in Marxist critique: capitalism is really an integrated system, this system has to be imposed coercively, liberals support and try to legitimate this process. I think this is only part of the story – and not everyone who tries to legitimate capitalism is a liberal. The point is that liberals don’t think of capitalism as an integrated system, they think of capitalist societies, or of their ideal societies, as an amalgam of autonomous fields (subsystems) which do not form a system except in a very loose sense, do not impose a way of life (but simply express an aggregation of individual choices or unfolding of human nature), and are not ultimately determined by political power (but at most ‘protected’ by it from ‘coercive’ forces). In practice, this is legitimation, in that they are supporting what is actually an integrated system which is imposed coercively. Yet it requires that they ‘really believe’ that capitalism is something else, and to act as if it was this ‘something else’, even if in doing so they have to oppose the needs of capital accumulation at a particular moment (this is the difference between an economic-corporate and an organic ideology).

There’s a certain social composition behind this, but it’s more precise than you seem to be thinking. One of the defining features of liberalism is that it defines a class peace between the state-class and the bourgeoisie or petty-bourgeoisie (or in wider versions the people) based on a strict limitation of the role of the state to certain spheres of social life (and its exclusion from others), the use of checks and balances to constrain the unfolding of the state’s inner logic, the absolute or near-absolute character of basic liberties, and the existence of a civil society autonomous from (and not constituted by) the state.

The current composition is, rather, a kind of fusion of the state-class and the bourgeoisie based on the unconstrained unfolding of the inner logic of the state (Kropotkin’s political principle / Agamben’s sovereignty) within a global sphere controlled by transnational capital. The sphere-separation has disappeared – this is most notable in relation to the invasion of everyday spaces by surveillance and micro-regulation, and the loss of autonomy of the professions, but it is not even true that specifically ‘bourgeois’ rights are insulated from the state (consider the issues of asset freezing, asset seizure, and eminent domain). Checks and balances have been corroded by the growth of executive power, ‘summary’ administrative processes, punishment-by-process, and ‘joined-up government’.

I’d suggest this involves a real change in the composition of forces. The transnational bourgeoisie feels sufficiently empowered by ‘globalisation’ that it no longer needs to keep the state-class in line, and can dispense with liberties and procedural constraints which, if they no longer threaten the bourgeoisie, are simply barriers to accumulation. Furthermore, capitalism has stopped needing the included stratum (or has stopped needing to make concessions to it). For the last century or more, liberals have mainly been ideologues of the included stratum (particularly the professions and ‘middle classes’, and – through its close relative social-democracy – the included sectors of workers). Today, the included stratum are disoriented and disempowered, and are mainly reacting by making immense compromises with the real power-composition so as not to become excluded. As a result, we see liberals systematically excusing things they would be condemned absolutely in the recent past. Hence, capitalism ceases to be liberal because it ceases to need procedural guarantees of autonomy from the state, and the included stratum cease having enough leverage to insist on even partial compliance with liberal values.

We also see liberalism being systematically sidelined by authoritarianism, populism and nationalism. These come from a rather different ideological composition: they are ideologies of the state-class, and of reactive networks. They seem to operate through the hegemonisation of atomised or reactively composed sections of the popular classes, either through integrative networks (e.g. patronage networks), or through the media. In their more aggressive forms, such compositions are explicitly defined against ‘liberalism’ and the ‘liberal elite’, and they are determinedly opposed to all unconditional rights, autonomy of subsystems, and checks and balances.

“recognising and visibilising certain processes doesn’t mean that they weren`t previously assumed, in particular I believe the use of coercion in the formation of a privileged individualised subjectivity in the bourgeois public sphere has always been absolutely assumed as constitutive in liberal theory”

I’m not sure as this is true. Liberalism as a legitimatory ideology operates the way it does precisely because it does not recognise any place for state construction in the spheres from which the state is excluded. Liberalism simply assumes that people ARE a certain kind of subject, and the role of the state is simply to leave these subjects alone, while providing certain services for them. Locke for instance assumes that people in the state of nature are already possessive individualists in the state of nature. Paine assumes that liberal rights can be deduced from people’s basic nature.

Of course in practice, capitalism had mechanisms to produce conformist subjects, but the idea that the state was a central part of this was anathema to liberalism. So when a Marxist says, “in fact your system rests on coercion to form subjectivities”, a liberal replies “no it doesn’t, it comes from the free relationships of individuals – YOU’RE the one who supports coercion, and that’s why my theory is better than yours”. In practice, the function of producing subjectivities was delegated partly to the ‘market’ (people will be coerced into conforming by economic necessity), partly to the professions which were themselves taken as neutral, partly to the functioning of ideology and the media, again taken to be neutral. The separation of these fields from the state was central to the account of their neutrality, and the resultant ‘plausible deniability’ that capitalism operates as a single, integrated system. Each of these fields was itself to be insulated from the state, or at most, protected in its autonomy. In order to sustain ‘plausible deniability’, the subsystems all had to have substantial autonomy, and a certain amount of drift, dysfunction and dissident activity had to be tolerated within them.

Hence, showing (for instance) that the media is not ‘neutral’, or that people don’t just ‘choose’ particular commodities but are pressured or manipulated into buying them, or that apparatuses such as education or healthcare actually serve functions for capitalism, were major tasks of Marxist and other critical theories right up to the early 1980s.

Today, it’s almost as if the point has been conceded – “everyone knows” that schools are there to prepare people for the workplace, that the media is directly promoting state values (think of police documentaries, or encouraging political snitching by news media), that ‘growth coalitions’ are explicitly trying to induce consumption. It’s almost as if they’re turning round and saying – ‘yes, we’re doing what you’ve always said we were doing before – and why not?’

The example of hijab-wearing is really no different from a great many similar examples regarding religious practices in liberal societies, in which liberals would come down firmly on the side of the right to such practices (for example, religious schooling, conscientious objection, Jewish arbitration tribunals, the Sikh insistence on turbans, etc) – not to mention other kinds of dissident practices (e.g. squatting, radical music, Mayday parades, political stalls). The existence of religious and cultural resistance to capitalist individuation, and of forms of subjectivity emerging from local community sites, are not by any means new issues, and they are issues where liberals would come down on the side of the anti-capitalist, to maintain their entire ideological composition. It’s only in the current climate of aggressive authoritarianism (and certain other eras of rampant authoritarianism) that pro-capitalists have taken the stance that every last vestige of resistance must be stamped out.

“the conception of liberal democracy you set out, in a very fundamental way could not have existed in Europe, without the violence and exploitation in the colonies” – I think you’re mixing up the conception/ideology with the entirety of nineteenth-century capitalism, which was by no means homogeneously liberal. That nineteenth-century capitalism depended on colonialism, I am not debating. Nor that liberals in this era accepted and promoted colonialism. However, they managed it in a particular way which allowed them to continue to adhere to liberal ideology while also supporting illiberal practices.

In order to function as an ideology, liberalism need to continue to believe that capitalism is not an imposed system, that the subsystems are absolutely autonomous, and that whatever regimes they choose to support are upholding basic rights (remembering that liberals are not theoretically obliged to support any and every capitalist regime, and historically have not done so). Logically, liberals should oppose colonialism as excessive state power, and they do, in cases such as the American Revolution. They wriggle out of opposing colonialism mainly by a gesture of exception: all human beings must be treated according to liberal theory, BUT certain peoples are not fully human and don’t count. As abhorrent as this gesture is, it explains completely why people were able to continue believing in liberal ideology without becoming anti-imperialists – as long as the exception remains viable, so does the ideology. (In my view, we’re already dealing with “recuperated” liberals in nineteenth-century Britain, since liberalism started out as a revolutionary ideology).

What I see happening with today’s composition is something completely different: mainstream supporters of capitalism, and a certain subsection of liberals who are tailing them, are effectively concluding that the rights and autonomies set up in liberal theory should not apply at all (or should only apply with such extensive exceptions as to render them impossible to exercise). Even if the application of the exceptions occurs at the same points, the excuse for the exceptions is total, not local. Hence, these “liberals” are accepting what a liberal cannot in principle accept while continuing to support capitalism: that capitalism is a total system which needs to be imposed coercively. That’s not modified liberalism, it’s something else.

The Gramsci reference is from Further Selections from the Prison Notebooks p. 352. It relates to Italy, and the bit I’d remembered was the last bit on ‘fatherland’ becoming synonymous with ‘liberty’.

Excellent Piece!

I think the parallel you make is really interesting, though not unproblematic. The question this seems to be raising to me is: is it possible to exist in a liberal public sphere, without being visibly individualised? Is the de-individualisation of the subject a fundamental threat to liberalism? There`s an obvious distinction to be made, the Piquetera chooses to cover her face as part of a conscious political action, whereas the Muslim woman would probably not claim a political motivation she`d say it is an act of personal piety. Yet obviously that’s not how its interpreted by the political class, and I suspect there`s a degree of truth in their suspicion that in both cases there is at least an element in which subjectivity is being constructed as collective as a resistance and an act of solidarity against a form of liberalism (neo-liberalism in Argentina and post-colonial Western liberal interventionism / secularism in Europe). The French Philosopher Bernard Henri-Levy went as far as to claim that the Niqab is “an invitation to Rape”, reflecting an idea that if you reject western liberal individualism you by implication abandon any claim upon human rights, so this shows how keenly felt this threat is by certain secular-liberal elites.

But then, if we accept that de-individualising the subject is a subversion of liberal democracy, then liberal democrats in Britain, Argentina or France are surely right to be against it, its not necessarily “othering” its just them defending their liberal politics. Also those of us who are not liberal democrats have to think about the consequences of what we`re arguing for. For example if we argue that collective identities have a role in the public sphere, then how does that relate to the rights of the individual. This is a live political issue, for example in terms of the “aggressive secularism” which has developed in Europe (particularly in Britain under New Labour in relation to Gay Rights legislation) do we demand that “citizens” leave their deeply held beliefs in the private sphere, or do we accept that these beliefs have a role in the public sphere i.e. doctors refusing to perform abortions, or hoteliers refusing to let a gay couple share a room.

There is clearly a tension between a collective and a individual political subject here which lies at the heart of debates on multiculturalism in Europe and the nature of democracy in Latin America and this tension is being articulated very much through the type of political struggles that you`re suggesting here, I think the parallel you draw brings this out very well.