Forensic Architecture: Cloud Studies (Whitworth Gallery) Exhibition

Arts & Culture, Exhibition, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, August 13, 2021 17:07 - 1 Comment

By Esther Kaner

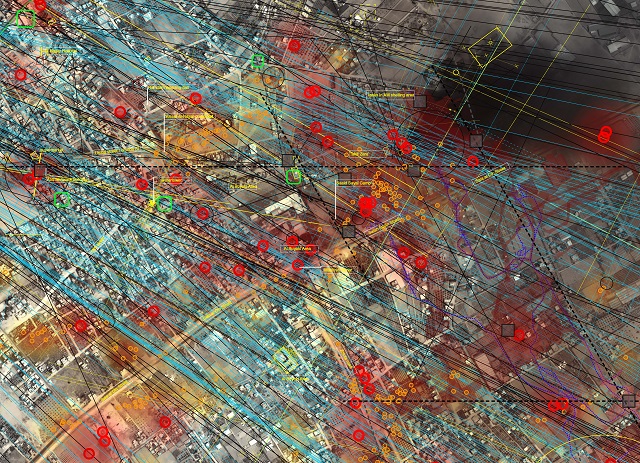

A composite image of every piece of spatial analysis conducted by Forensic Architecture and Amnesty International in relation to Rafah on 1 August 2014. (Forensic Architecture).

In 2008, the Israeli military launched a bombing campaign in Gaza, killing over one thousand Palestinian civilians. Here begins Cloud Studies, Forensic Architecture’s latest exhibition at the Whitworth, consisting of two single channel films and a series of smaller installations. The headline film immediately immerses us in a cloud of dust, an insidious grey shroud emerging in the wake of necropolitical destruction.

“Mobilised by state and corporate powers, toxic clouds colonise the air we breathe across different scales and durations”, states the collective. Bombs erupt and explode. They are dropped either in isolation or in coordinated groups, yet we understand their effects to be temporally enfolded, condensed into isolated moments of utter destruction. But what of the traces they leave?

The term ‘necropolitics’ was coined by African philosopher Achille Mbembe to describe how state technologies of violence create ‘death-worlds’ — “new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to living conditions that confer upon them the status of the living dead”. The Gaza strip, subject to repeated acts of targeted aggression and paralysing economic blockades, is one such necropolitical formation.

But it is not just the Palestinians’ exposure to mass death that confers upon them the status of the ‘living dead’. Every act of violence leaves a cloud, literal or metaphorical, a suspension of noxious chemicals and conditions, that inscribe such depredations upon marginalised bodies. It is through this lens that Cloud Studies explores the formation and dispersal of clouds as technologies of violence and colonialism, purposely dispersed by states and corporations in an attempt to deprive populations of the ‘universal right to breath’.

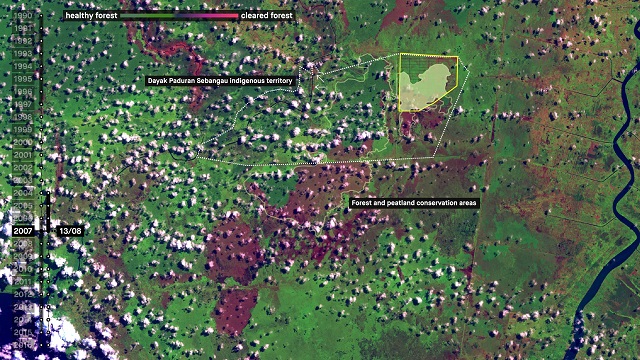

The exhibition surveys a variety of contexts, ranging from the 2014 bombing of Rafah to Indonesian deforestation. In every case, clouds form part of the architecture of slow violence. The term was developed by Rob Nixon to describe “a violence that is neither spectacular nor instantaneous, but rather incremental and accretive”, scarcely recognised as violence because of its dispersal “across time and space”.

By way of example, Nixon draws upon the US’s nuclear testing regime in the Marshallese Islands. Between 1946 and 1958, 23 nuclear weapons were detonated on Bikini Atoll in an effort to develop weapons of mass destruction. This led to the mass dislocation of hundreds of residents and the poisoning of the surrounding sea and soil. The destruction has since been driven into indigenous bodies; well into the 1980s, Marshallese women were giving birth to severely deformed babies, “more jellyfish than child”, in the words of Marshallese poet Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner. A 2005 US Senate Hearing suggested that fatal birth defects were continuing to appear in Uitrik Atoll at the time of writing, over 300 miles away from the original testing sites. The enormous mushroom clouds that came to represent the programme have inseminated the bodies of humans and non-humans in the island nation with radioactive particles.

Nixon alerts us to the ‘representational, narrative, and strategic challenges posed by the relative invisibility of slow violence’, asking:

In an age when the media venerate the spectacular, when public policy is shaped primarily around perceived immediate need, a central question is strategic and representational: how can we convert into image and narrative the disasters that are slow moving and long in the making, disasters that are anonymous and that star nobody, disasters that are attritional and of indifferent interest to the sensation-driven technologies of our image-world?

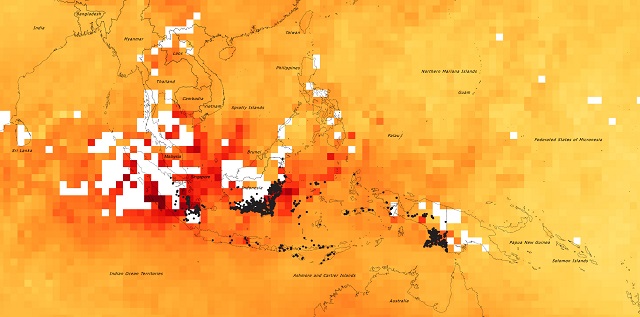

Cloud Studies offers techniques to make slow violence visible. Through a range of methodologies, including fluid dynamics and 3D modelling, Forensic Architecture pieces together the lifecycles and dynamics of clouds as they besiege the colonised and oppressed. The atmospheric consequences of forest burning are mapped through the visualisation of gaseous concentrations in Indonesian rainforests. Security footage is used to monitor the use of teargas in mass protests and civilian uprisings. The erosion of black cultural heritage in the American South is revealed through comparisons of historical and contemporary maps showing the disappearance of sacred groves.

Carbon Cloud and the sources of fire, 2015 (Forensic Architecture).

Clouds, and the slow violence they represent, resist simplistic notions of causality. Temporally and spatially diffuse, clouds cannot easily be traced or attributed; “their dynamics are governed by nonlinear, multi-causal logics”. As such, “cloud studies is forensics without inscription”, states Cloud Studies’ narrator. Legal and political doctrine conceives of violence as temporally bounded, reducible to isolated events with clearly demarcated victims and perpetrators.

The absence of such easily definable borders in cases of slow violence allows for the avoidance of accountability and the spread of misinformation. As such, Forensic Architecture maps the spread of ‘information clouds’, formed in the wake of the Syrian government’s release of chemical weapons upon its own civilians. Political actors and commentators hide amidst the clouds’ haze, manipulating the course of events to favour given ideological positions and geopolitical interests, showing little regard for the experiential realities of the clouds’ victims.

In situations unamenable to simplistic narrativization, we must foreground the lives and experiences of those at the interface of such harm. Cloud Studies alerts us to the immense power of testimony and bearing witness. It is through the assembly of testimonials that Forensic Architecture gives shape to otherwise indiscernible events. The consequences of herbicide spraying by the IDF along the Gazan border are made visible through photographs and samples of damaged crops. A timeline of the 2020 Beirut explosion is assembled by an analysis of video testimonials indicating smoke trajectories. The Grenfell Tower fire is modelled with the aid of survivors.

The work of scholar activist Flora Cornish, too, shows the value of witnessing. Having meticulously documented events unfolding in Grenfell’s aftermath, she is compiling a timeline that attests to many of the disaster’s lingering after-effects, including persistent soil toxicity. Through careful co-production and knowledge exchange, her work makes visible the consequences of structural neglect in the aftermath of state violence.

In attending to slow violence’s scattered effects, we are alerted to new forms of resistance. Borrowing from Donna Haraway, Cornish uses the phrase ‘staying with the trouble’ to understand why community organisers and Grenfell survivors continue on despite their abandonment. Communities continue to garden on the contaminated soil, fully aware of the potential risks. Yet in doing so, they provide a vision of communal care that imagines other ways to live amidst toxicity.

Similarly, Manuel Tironi describes the actions of residents of Puchancaví, Chile’s most heavily polluted industrial compound, as ‘hypo-interventions’. Here, small, relational acts of care and survival, like tending to wounded plants and wounded bodies, create “the conditions for the flourishing of life in a devastated landscape”. Resistance, especially in the face of destruction and precarity, rarely conforms to the assumed public spectacles or linear ‘successes’ and ‘failures’ through which we have come to understand activism. It is instead through the everyday that slow violence is both enacted and resisted.

As dominant frames of accountability thus encourage a focus on isolated events, slow violence and the resistance it generates are left largely ignored, unamenable to systems of evidence-gathering that fail to draw the necessary connections between acts of aggression and their dispersed, toxic after-effects. Cloud Studies shows us the power of visual documentation and creative assemblages in challenging state logics that seek to silence experiences of protracted suffering. It gives us tools to unearth struggle as it is suppressed under the weight of formless and diffuse threats. It emphasises the primacy of testimony as a form of resistance, giving shape to the amorphous, deadly clouds that envelop entire populations, and moving us further toward accountability and closure. If we are to oppose colonial and oppressive structures, we must engage in the slow work of bearing witness and piecing together stories. Forensic Architecture offers insight into how we might do so.

[All photos: Forensic Architecture]

Cloud Studies | Forensic Architecture

2 July–17 October

Venue: The Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK

Free – ticket required

From the investigation “Ecocide in Indonesia” (Forensic Architecture).

1 Comment

CAROLE HICKLING

On a visit to my sister who lives in Manchester ( I presently live in Plymouth which rather lacks thought provoking culture ) we went to the Whitworth Art Gallery where I was amazed and emotionally spent by the exhibition on Cloud Studies by Forensic Architecture…The personal impact of the exhibition has stayed with me and so I have spent much time on line finding out more, shared the experience with colleagues and will be going back to Manchester before October 17th to see exhibition again.

Thank you for some outstanding work and for exposing my thoughts, brain and emotions to an incredible experience which I will never forget. I have travelled extensively and always worked in caring professions in some poverty stricken areas and with very vulnerable people but your work has really opened my eyes.

Thank you