Analysis The ‘Big Society’ Riots

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Thursday, August 18, 2011 16:42 - 4 Comments

By Neal Curtis

By Neal Curtis

While the English riots emerged out of progressive and genuinely political concerns regarding discrimination, exclusion and poverty the abiding image was of groups of youths looting brand name stores for trainers, TVs and games consoles. What was peculiar about the riots was how this supposedly anti-establishment expression of anger nevertheless rigidly conformed to the ideology of consumer culture that stipulates our ultimate goal should be the accumulation of commodities.

For many commentators this manifestation of the ‘get what you can’ mentality validated David Cameron’s Big Society agenda, which, despite being rather vague and nebulous, has come to frame the policies of the coalition government in its privileging of initiative and responsibility over entitlement and rights. However, if we trace the genealogy of this idea we will find that it emerged out of a philosophy of ruthless self-interest and continues to promote such a stance. Despite being dressed up in the garb of middle class morality it is a philosophy of naked competition and self-regard.

Although there is little detail as to what the ‘Big Society’ is, its primary function was to appeal to the post-Thatcherite social democratic turn. In doing so, it was designed to resonate with Labour supporters, while remaining critical of supposedly big government and public intervention, thus remaining true to central conservative values.

In truth, though, the Big Society only pays lip service to society. It remains allergic to any notion of the collectivity which society necessarily implies. ‘Collectivity’ here need not assume a unity of purpose. However, society is a set of relationships that precedes each and every individual and requires a strong sense of our being joined for it to be meaningful. It is, then, anti-state rather than pro-society in any genuine sense: opposed to doing things for others, who it purports should be doing things for themselves.

The Big Society recognises some element of connectivity, but only understands it as a loose and rather shallow network of individuals. Despite the rhetoric, the individual remains the absolute foundation of this thinking, and in its antagonism to the state it is an ideology that promotes further rounds of privatization, sanctifying the use of markets in all areas. In response to the riots, then, what is named a ‘social fightback’ is firmly articulated as the responsibility of individuals and their families, rather than that of society.

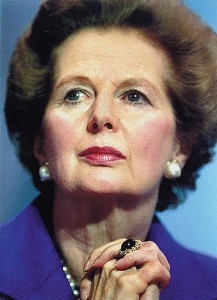

It continues to surprise me that, in the acres of commentary on the riots, little has been made of the fact that just over 20 years ago Margaret Thatcher refused to countenance the very idea that society existed. In her famous interview for Woman’s Own magazine in 1987 she stated that there is no such thing as society, only individuals and their families.

It continues to surprise me that, in the acres of commentary on the riots, little has been made of the fact that just over 20 years ago Margaret Thatcher refused to countenance the very idea that society existed. In her famous interview for Woman’s Own magazine in 1987 she stated that there is no such thing as society, only individuals and their families.

It seems, then, that Cameron has done a Lazarus: not only is society back, it’s BIG. But, as you’d expect, this reanimation is all done with smoke and mirrors. We can make the jump from there being no society to it being BIG only because the Big Society is a euphemism behind which is hidden the fact that it continues to privilege the private over the public, the individual over the state.

Thatcher’s denouncement of society came at the height of a political, social and cultural revolution in which well-being was determined by material wealth alone. It also introduced the dogma that if the market can’t support something, i.e. it can’t turn a profit, it is illegitimate. The two primary motors of Thatcher’s revolution were greed and avarice. With it came a massive increase in the division between rich and poor, a burgeoning consumer culture, and a credit-fuelled boom that supposedly pulled Western capitalism out of stagnation.

In the end though it only led to the economic disaster that has seen more money pulled out of public projects that were doing something to placate the worst effects of the increased social exclusion and relative poverty that the market revolution brought about.

The riots certainly have social causes. They cannot be addressed without some focus on the lack of prospects for many of England’s youth (one in five is unemployed), as well as persistent racial and ethnic tensions, and the ways those tensions are policed. But they also need to be assessed in relation to a society that is totally in thrall to a philosophy of privatised self-interest. In this sense, the riots, especially those that followed the events in Tottenham, were the naked expression of the dominant ideology, stripped of the veneer of middle class civility.

However, tracing David Cameron’s Big Society back to Thatcher’s argument that society doesn’t exist is only part of it. To understand the lineage of the riots we need to trace the ideology of privatised self-interest back to its origin in the writings of Ayn Rand which were a significant influence on Thatcher. Indeed, Thatcher’s aphorism can be traced to an essay by Rand entitled ‘The Objectivist Ethics’, collected in her book The Virtue of Selfishness.

That title alone gives a sense as to where this leads, but let me set it out in a little more detail. In the essay, published in 1961, Rand wrote: ‘there is no such entity as “society”, since society is only a number of individual men’. She then goes on to declare why the individual should be privileged: ‘An organism’s life is its standard of value: that which furthers its life is the good, that which threatens it is evil’.

In other words, the fact of his existence and the need for survival determines what he ought to do: ‘his own life’ is ‘the ethical purpose of every individual man’. Rand goes on to claim that looters and thieves are parasites and animals because they do not obey the human need for productive work in the furtherance of life. But the addition of productive work is a very fragile moral regulator when your philosophy posits the individual as his/her own ethical purpose.

For Rand, looting is destructive of the productive work of others, but such an argument is possible only if she ignores the destruction that takes place under the guise of productive work within a capitalist regime of accumulation: the stripping of natural, social and human resources, the externalizing of costs, the break-up of no-longer-feasible productive communities, all of which can be said to have made their own contributions to the recent unrest in English cities.

In the introduction to The Virtue of Selfishness, her position is stated even more starkly: ‘concern with his own interests is the essence of a moral existence’, and ‘man must be the beneficiary of his own moral actions’. What is more, altruism leaves man ‘without moral guidance’, and in so far as it counters a life centred on an individual’s own interests, it counters the ultimate good, and must in turn be understood as evil. Indeed altruism is taken by Rand to be the moral corrupter of the age.

Altruism, or putting others before oneself, was responsible for every form of 20th century totalitarianism where man is reduced to a sacrificial animal on the altar of the collective. In her book Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal she writes: ‘altruism is not a doctrine of love, but of hatred for man’. In the assault on all things public that was signalled by the ascendency of Thatcherism this philosophy of self-interest has gradually invalidated any meaningful understanding of society as a condition of mutual dependency, collective production and joint responsibility. Society has not broken down through the erosion of individual discipline; society was actively dismantled by promotion of the disciplined individual ruthlessly pursuing his or her own interests.

Altruism, or putting others before oneself, was responsible for every form of 20th century totalitarianism where man is reduced to a sacrificial animal on the altar of the collective. In her book Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal she writes: ‘altruism is not a doctrine of love, but of hatred for man’. In the assault on all things public that was signalled by the ascendency of Thatcherism this philosophy of self-interest has gradually invalidated any meaningful understanding of society as a condition of mutual dependency, collective production and joint responsibility. Society has not broken down through the erosion of individual discipline; society was actively dismantled by promotion of the disciplined individual ruthlessly pursuing his or her own interests.

No matter how BIG the rhetoric claims society to be, unless it genuinely returns our association with others and our mutual dependency to the centre of the political agenda nothing will change.

Society is not a group of largely white people with new brooms momentarily sweeping their streets. It is the recognition that we are all responsible for what happened on those three nights because in the pursuit of what is best for ‘me’ we have forgotten what is best for others.

One of the responses to the violence has been a renewed call for citizenship studies but this would be little more than a programme of passification. In these times, when an alliance of corporate bosses, financiers, politicians and media moguls manage society for their own interests—dividing and conquering through the cult of the individual—citizenship studies should compel everyone onto the streets to demand our society back and reject the empty platitudes of the plutocrats that govern us.

Neal Curtis is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Film, Television and Media Studies at the University of Auckland. He is the author of War and Social Theory: World, Value, Identity (2006), Against Autonomy: Lyotard, Action and Judgement (2001) and editor of The Pictorial Turn (2010). His latest book, Idiotism: Capitalism and the Privatisation of Life was published by Pluto Press in November 2012.

4 Comments

Az

Very well written. Rand/Thatcher are not only HIGHLY flawed in their ideologies in the sense that they claim “there is no society”, but they clearly have underlying psychological problems which can be easily identified if one takes into account attachment styles, insecurity and even Freud!

“In her book Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal she writes: ‘altruism is not a doctrine of love, but of hatred for man’..” – someone didn’t get some lovin as a baby!

That aside, like Sofia said radical action definitely needs to be taken, but it has to be organised and ultimately aimed to break Rand’s conservative ideologies which have been taken up by the working class thanks to capitalism…!

SamJam

Good article and the point about the opportunism, individualism and looting happening from the top down is certainly true.

However I think there is also a danger of overemphasising the depolitical nature of the riots. I think where you write–“what was peculiar about the riots was how they rigidly conformed to the ideology of consumer culture”–you have done so.

To begin with I don’t think there is much “peculiar” about the fact that the riots contained looting. Off the top of my head this was a large part of the rioting in Northern cities of the US in the 1960s, The LA riots 30 years later, and the Caracazo in Venezuela. And yet all these riots, are regarded at the time, and now looked back upon by all sides, as intensely political.

How this was political becomes more clear when you look more closely at the looting itself. A lot of the stealing was really menial (we’ve heard about the kid who has got 6 months for stealing a bottle of water). Other times shop windows were smashed but nothing was being taken. A young girl interviewed on the BBC who had joined in with rioting spoke about this showing the government, the police and the rich that ‘we can do what we want’. In other words it was precisely about power for a lot of people.

Secondly this wasn’t just about looting as you suggest. Much of the rioting, around the country, actually targeting the police. In your city of Nottingham 6 police stations were attacked. This isn’t excessive consumerism or even less rampant individualism. People carry out such combat collectively and at great personal risk.

Finally there is a danger in over extrapolating from one event. We keep hearing from the political and media class that this is emblematic of a broken society where people will too easily turn to crime and gangs and so on. The truth, according to the British Crime Survey BCS the rate of lawbreaking is “around the lowest level ever reported”.

http://www.newleftproject.org/index.php/site/blog_comments/ignoring_the_british_crime_survey

It is important, given the editorial line of most of the mainstream media, that the dissident media adequately represents these dimensions.

Andy

I’d add that the “what’s best for me” thing is applied VERY inconsistently by the New Right, and in fact the dominant ideology at least in the media today is not individualism but a kind of retro-1950s authoritarianism which dismisses every claim of oppression or injustice as selfish. The people opposing the student protests, condemning looting and so on, are constantly coming out with slogans like, “you can’t always get what you want” and “back in my day, you just put up with it”. This has infiltrated into official ideology via fascist practices such as ASBO’s, draconian responses to minor deviance, and a general intolerance of difference. This has left individual rights at a very low level – no right to protest, no freedom of association etc – and even to the point of the sanctity of property being violated, for instance in “asset forfeiture”. So it’s too simplistic to say that there’s a general culture of “everyone for themselves”. The belief that individual rights are trumped by “security” or “community” has become insidiously common, and is used by the system to ruin lives at whim. In other words, it’s a mix of “no obligation of the better-off to anyone else” with “the poor have to play by the rules – or else”.

In a class-divided world, there are of course point at which people’s concern for others no longer extends: the point of the class antagonisms, when different claims become incommensurable. The bigots care about community as long as it reinforces their status-superiority and doesn’t require them to take on proactive duties to others – especially in terms of redistribution. To that extent they are individualist, but only in the property sphere – not at all in the normative sphere. Actually I think their fatal flaw is their belief that people remain obliged to some kind of macro-unit (the nation, “society”) unconditionally, regardless of how “it” treats them. This is symptomatic because the macro-unit is always an alibi for their own group-interests. It amounts to a claim that they, as the ‘nation’, are owed respect and compliance with their wishes as a matter of course. Others, in contrast, are owed nothing – they are always “too entitled”, since the whole world belongs to the predatory in-group.

On the other side, people who are radically excluded, who are constantly abused and violated by the in-group, are of course not likely to feel any obligation to the in-group – why should they? They may well be aware of social interdependence, but this will be channelled into microsocial groups of people they can trust absolutely, against a hostile world. The problem is that they are silenced: there is no dialogue between them and the in-group, because the in-group’s frame locks them out. An insurrection is an interruption of the monologue, but now no holds are barred in restoring the monologue and silencing the additional voice which has emerged. This is how the illusion of “consensus” is built from a conflictual social situation.

It’s less helpful to say “we’re all responsible” than to say: the in-group has caused this with its constant social war against the poor. The bigots can’t shit on people all the time, and expect to be loved for it. They can’t complain when people return the violence which the bigots have been dishing out constantly. We need to reject absolutely the illusion of generalised obligation to any social macro-unit, and insist instead that social peace is only possible through dialogue across difference. Since the bigots started the social war and have never been punished for it, the actions of the excluded MUST be forgiven. No to the return of molar “society” – yes to a multivoiced, relational view of social relations.

Thought this was a brilliant piece! Great contextualisation.

Especially like “Society is not a group of largely white people with new brooms momentarily sweeping their streets. It is the recognition that we are all responsible for what happened on those three nights because in the pursuit of what is best for ‘me’ we have forgotten what is best for others.”

There are many problems with superficial, aesthetic exericises such as #riotcleanup so I was glad to read that. To address the underlying causes here more radical action is certainly necessary!

Thanks!