Review: 1395 Days Without Red Film

Film & TV, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Wednesday, October 19, 2011 3:54 - 1 Comment

Beyond a set of doors marked only by a pair of photographs, a man sits behind a table. On the side of the room facing him there are some books, a coffee table with refreshments, and an elongated, hand-drawn diagram, plastered across half of the respective wall.

Beyond a set of doors marked only by a pair of photographs, a man sits behind a table. On the side of the room facing him there are some books, a coffee table with refreshments, and an elongated, hand-drawn diagram, plastered across half of the respective wall.

Surrounding a line-image of the horizontal channel contained within are aerial photographs of successive urban junctions. The images are of Sarajevo, of intersections along a part of the city named Sniper Alley during its siege at the hands of Serb/Yugoslav forces that begun in 1992, lasting over 4 years. Such is the topic of Šejla Kamerić & Anri Sala’s films, originally conceived as a joint project (in conjunction with starring conductor Ari Benjamin Meyers), eventually spawning two individual films, available to be seen here for free.

1395 Days Without Red derives its name form the warning issued by the government against wearing bright colours, lest you became a target for the snipers camped in the surrounding hills. Sarajevo sits in the Dinaric alps at 1,700ft with peaks nearby reaching over 6,000ft, providing ample elevation to survey – and pin down – the inhabitants of the city.

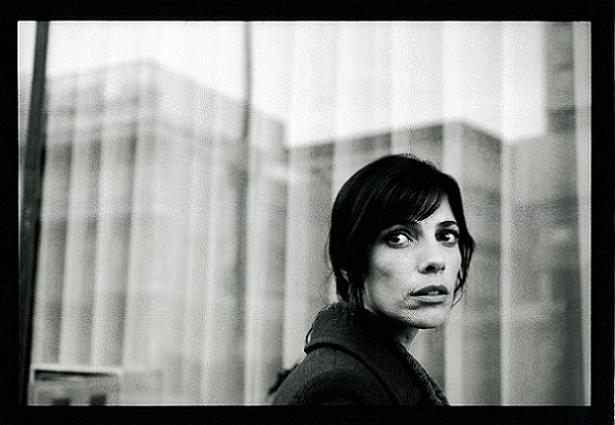

The film’s narrative consists of one woman’s journey to a room in which she rehearses Tchaikovsky’s 6th, also known as the Pathetique. As she makes her way across the city she traverses the series of intersections, spanning some 2 or so miles, that make up Sniper Alley. Although we see her cross one junction after the next in geographical order, one step closer to her destination at a time, the journey is not chronologically linear but jumps forwards and backwards in time.

Our understanding of how time passes in the film is not engendered through the use of dialogue (there isn’t any.) Instead, temporality is structured in relation to the practices she attends. The film alternates between crossing and rehearsal scenes, with the chronological position of the crossing relative to the part of Tchaikovsky’s piece the orchestra are currently playing. In other words, whether they are rehearsing a part that comes before or after the last in the previous scene dictates whether we have pro-/regressed in time. In doing so a dialogue is opened between Past and Present, inviting the viewer to reflect on remembrance (in this case relating to a traumatic event) and the act of committing to memory (as when learning a piece) itself.

Music does not just structure the film’s chronology, but also its pace, mood and emotion. Tempo is reflected in the speed with which she moves, pathos in her facial expressions. In this way Tchaikovsky’s piece holds an unrivalled importance in structuring the film: each event has its musical counterpart, with the sentiment of one mirrored in the other. What makes this use of music in film interesting is its alternativity (as opposed to simultaneity), with each counterpart waiting for the filmic space to be cleared before relaying.

Breaking the film up this also way serves to emphasise its weightiest aspect. Aside from this original and powerful paralleled narrative, the film’s most laudable achievement is its compelling representation of the siege’s affect on life, all in such a minimalised fashion. Without dialogue, the film focuses on just one aspect of the way in which life changed under siege; the bigger picture is replaced by a snapshot, and the siege becomes more tangible. Forced to focus on the minute details that comprise a simple and singular aspect of quotidian routine, we are encouraged to draw parallels between her emotion and ours. Through extended exploration of these feelings, we become aware of their pervasiveness.

Thus, it is the individualisation of the event that renders 1395 Days Without Red so strong. By relating each crossing to a different rehearsal, we are reminded that the psychological turmoil caused by the threat of violence would have been repeated not just during the course of a single journey, but over months and years. We are made to think of the dull, indefinite, ultimately unforgettable pressure placed upon the city’s inhabitants as a result of national conflict.

A connection is also made between life under siege and preparation for a recital, aided by the minor yet not altogether insignificant fact that Sarajevo’s Symphony Orchestra were not put off by the siege and continued to perform throughout its course. It goes without saying that life under siege and musical performance are wholly comparable, but by placing them side by side – as has been done here – whatever aspects of the human condition they might share are permitted to come to light.

There is little denying the efficacy of the film’s structure as a platform on which both the grand and the minute are explored in their opposites. In doing so, Šejla Kamerić & Anri Sala have managed to make a modern silent film that achieves so much by saying so little.

1395 Days without Red (excerpt) / (running times)

1 Comment

Ocho propuestas artísticas para todos los gustos « Surcos en Vinilo

[…] 2. Anri Sala, albanés, representará a Francia en la Bienal de Venecia de 2013. Es un artista polivalente y uno de sus campos de acción es el videoarte. En este pequeño extracto de 1395 Days Without Red se puede ver su poderío visual más allá de la historia que narra. Aquí una crítica. […]