Essay Creating the Future: Victory Begins with Defeat

Features, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Monday, June 20, 2011 0:00 - 5 Comments

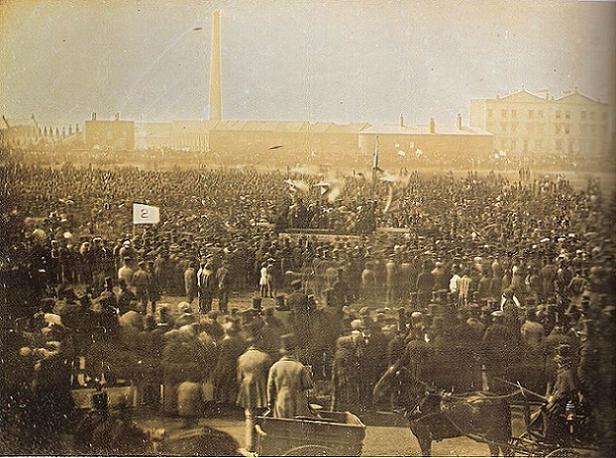

Mass meeting of Chartists on Kennington Common in 1848

By Paul Schloss

We have full political rights, guaranteed both by the law and the culture. Universal adult suffrage ensures that we can elect the government of our choice; and we do when the time comes. Occasionally we are called on to pay homage to the Queen and her family, technically we are her subjects, but generally it is the ordinary person, who works hard and pays their dues, who we praise; and who we are a little afraid of – they hold the power now. The politician is subject to us, and we have absolute rule on election day, when we coronate the leader of our choosing. We live in a popular democracy, a model, we are told, to be exported to the rest of the world; the voter makes it so.

The Chartists won, though it took many generations for their radicalism to become the common wisdom of the nation and its political establishment; the most conservative when it comes to institutional reform and parliamentary change. That victory was achieved outside Westminster and the established political parties. Though how it was achieved is a complex story. After the 1832 reform act the “working men of Great Britain… were still almost entirely without direct representation in parliament.” Yet thirty years later the leading politicians had accepted the inevitability of voting reform, although there was wide disagreement on how far it should be extended, as many did not want the working classes to have the vote.

However, following trade union agitation, and unrest at Hyde Park, which frightened the “wealthier classes [and] convinced Conservative opinion that electoral reform could not be delayed”, the 1867 reform act was passed, and added nearly a million new voters to the electoral roll, to give working class majorities in the towns.

For Llewellyn Woodward, whose remarks I have quoted, the Chartists were a “pathetic failure”, their reasoned schemes for parliamentary reform taken over by the masses and demagogues, which had led to a final “ludicrous” collapse around 1848, when internal failures and a strong police presence prevented a massive demonstration through London, which was to present its demands to parliament. The momentum gone, the game was over and the movement collapsed. Woodward is describing the narrow world of party politics, where everything is seen in the short term; and its wider repercussions are invisible to the contemporary, and overlooked by the historian.

Later in the book, but in an oblique way, he recognises the success of the Chartists: it forced the working class intellectuals to think of new ways to achieve their demands, which were essentially economic, not political. This led to the rise of more organised and successful trade unions. Though it would be wrong to attribute the later achievements merely to better organisation, and thus a more cohesive and effective political force. The culture of the times had to change too. How this happens no-one knows, but it involves a combination of material factors – in this case they would include the decline of agriculture, the rise of industry, the growth of the cities and the developing relationship of the classes – and ideas and ideologies, which are intimately connected, though not necessarily caused, by them.

More organised and effective trade unions help change the culture and this change in turn helps them. We capture something of this in Woodward himself:

It is mere speculation to ask how near England was to revolution during these years; the credit for keeping the peace may well be divided between different classes of Englishmen, though the sympathy of later generations will lie with those thousands of over-worked under-nourished labourers to whose unlettered minds Chartism brought at least hopes of redress and betterment. (The Age of Reform, England 1815-1870)

Radicals are usually ahead of respectable opinion, and this is a problem for them; as their ideals and programmes are subjected to repeated failures – in the short term. For the common wisdom of today was the revolutionary rhetoric of a few decades ago. Coming to prominence in the 1960s, the call for Welsh devolution became a radical cause in the 1970s, only to be massively defeated in March 1979. All was over, or so it seemed. Yet less than 20 years later self-government came to Wales, to be extended last year. Anthony Barnett compares these new constitutional changes to an earthquake in British politics, although he is thinking primarily of Scotland, particularly the recent results there; and the spectre of Scottish independence.

To be radical is to accept that much of what you do is not going to win immediate results. It is to be a battering ram that weakens today’s city walls, which will fall many years later. It is to provide the means to undermine the current establishment; creating new sources of resistance and reform; out of which new ideas, and subtle changes in feeling and opinion, will emerge, exposing today’s respectable opinion as old-fashioned and out of date.

Political change relies to a large extent on factors outside politics. Some campaigns are successful and have immediate effects, with changes to policy. Thus the aggressive campaign to ensure a Welsh speaking TV channel in the 1980s, which included a leading establishment critic, Gwynfor Evans, going on a hunger strike, to keep up the pressure on the government. A tiny event in British history, but how important has S4C been in helping to create a sense of a Welsh political identity, by providing a cultural responsiveness to self-rule; and how much has it contributed to Barnett’s “shifting tectonic plates” in a British politics which he believes is in “terminal decline”?[1] Generally though these campaigns will lead to an adaptation of the existing system, a fine-tuning of a political culture with its own values and priorities, geared to the interest of its most powerful patrons.

One of the reasons for this limited success is because politics is only a tool, which many people mistake for something substantive in its own right. Politics is about the distribution of power and wealth, whose outcomes will be determined by those who hold that power and those riches; though their actions will be limited by the culture and ideologies of the times. Before the rise of modern democracy and the professional politician Westminster was run by the powerful and wealthy; who for a long time were linked to the landed aristocracy; which created interesting tensions within the political establishment during the 19th century, and which helped reform – the conservatives and the workers were often both opposed to the industrialists, and the free trade liberals who championed their cause.

That is, before the 20th century the politicians both owned the country and ran it. The success of the Chartists, and the later reformers and revolutionaries, was to separate, to a large degree, the ownership of the country from its management – the modern MPs run it on behalf of others; mostly big business. But they have been responsive to other centres of power: the trade unions, the shop steward movements, its radical effects scattered throughout 20th century labour history, the municipalities, the state bureaucracy; as well as the aristocrats.

Modern day politicians do have power, though some exercise it better than others. However, most of their actions are determined by forces outside of their control; something the press and the politicians themselves often overlook, because of vanity and self-interest; and a certain ideological blindness; though we see it a little more clearly in other countries – in Japan, for example, where it is bureaucrats who rule, and the politicians who manage the population; acting as safety valves, to release the pressure when public opinion becomes too intense.[2] One consequence is that the culture overrates their importance, concentrating more on the tangible qualities of particular personalities rather than the institutional and structural causes that usually determine their actions. People are more interesting than institutions, and this is reflected in the press coverage; where elections and party manoeuvrings monopolize the political discourse – they are politics, for the majority.

Most people understand the world through the newspapers and TV. Their politics is therefore based on opinion rather than true knowledge – to understand events requires hard work and plenty of time, something we don’t have, we are told -, and thus they are dependent on the quality of the reporting, the depth of knowledge and insight of the journalists and commentators. It is the newspapers that provide the conventional wisdom for most people. Yet, when it comes to who owns the country, they concentrate on the servants and not the masters, the decorative façade and not the structure underneath.

This emasculates reform, but is perfect for reaction. Colin Leys in his classic Market Driven Politics notes how big business is always awake, always intent on reversing the social gains that has reduced its power over the last century. Thus its relentless onslaught on our public institutions and the idea of public service; seen as threats to its own interests, both commercial and ideological. Politics for a large corporation is one of its tools, part of its business plan, and it will spend a lot of money to ensure it works properly.[3] Nearly all of this work is behind the scenes in offices in and around Whitehall; and in institutions across the land. Boring and rather difficult to track and explain it is therefore ignored and dismissed – news must be entertainment too, especially today with the corporatization of the media.

The early Chartists, like modern CEOs, recognised the importance of politics as an instrument. They were fully aware that it wasn’t an end in itself:

Fellow-countrymen, when we contend for an equality of political rights, it is not in order to lop off an unjust tax or useless pension, or to get a transfer of wealth, power, or influence, for a party; but to be able to probe our social evils to their source, and to apply effective remedies to prevent, instead of unjust laws to punish…

And if the teachers of temperance and preachers of morality would unite like us, and direct their attention to the source of the evil, instead of nibbling at the effects, and seldom speaking of the cause; then, indeed instead of splendid palaces of intemperance daily erected, as if in mockery of their exertions – built on the ruins of happy home, despairing minds, and sickened hearts – we should soon have a sober, honest, and reflecting people. (Address to the Working Men’s Association, from The Early Chartists, edited by Dorothy Thompson. Emphasis in original)

The language is old but the intention is clear: the society must be transformed, with political rights emerging out of the cultural and economic changes necessary if the causes of the present injustice are to be eradicated. Central to this transformation was education, but of a quite specific sort: a critical understanding of the real factors, the causes, of industrial oppression. This knowledge another kind of instrument, used to undermine the ruling establishment.

They were right, and the culture did change, far beyond what they imagined possible – today’s universal suffrage for all adults makes their pleas of votes for working men look antiquated and reactionary. But these new changes didn’t come from nowhere. They grew out of a restructuring of the British economy around the fin-de-siècle, as the empire expanded and competition for world trade became more intense, with increasing pressure on costs and wages.

At the same time there was consolidation and growth in the trade union movement; while a working class party was formed in the 1890s, to directly represent their interests. Here was another time of radical ferment, culminating around 1919, its activity the beginnings of a nascent welfare state. The Labour Party was important in this transformation, but not so much as the threat poised by organised labour, and its increased power, obtained during that war. Although the new social reforms were essentially liberal, a modification of the economic system to distribute its rewards a little more fairly, and were in part designed to stop socialism and revolution, they were important in their own right, while laying the foundation for more radical reform in the future.

In his book Labour People Kenneth O. Morgan writes how the Labour Party became a “popular front” after 1900, with a wide spread of groups and political opinion; its composition dominated by the working classes and the trade unions; the middle class socialists holding a “disproportionate influence”.

This unstable coalition was much more conservative than its parts, especially the membership of the major industrial unions, where workers’ control of the mines and firms was advocated by some in a major statement, “the Miners’ Next Step” from South Wales. In a sense Syndicalism was a threat to the British establishment in a way that the Labour Party never was. It threatened the economic order, on which British politics rested, and it scared the ruling establishment; who listened to it in time of war.

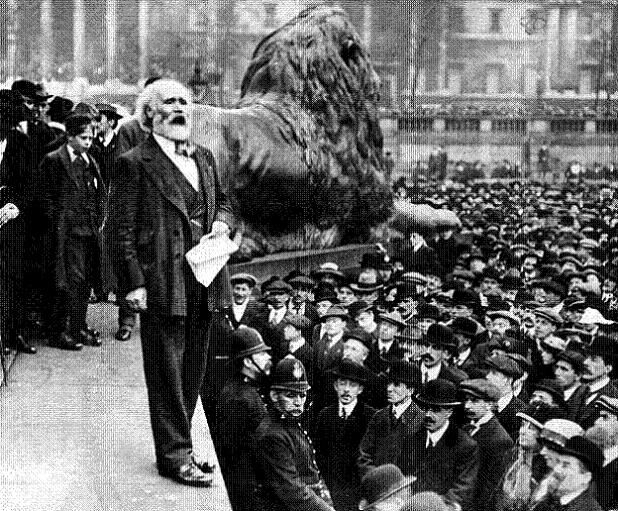

James Keir Hardie addressing a crowd in London’s Trafalgar Square.

In his book Morgan gives a sketch of the founder of the Independent Labour Party: Keir Hardie. It is worth summarizing some of his attributes and beliefs:

- A good parliamentary performer

- A journalist and “all-purpose, all-weather propagandist”

- An internationalist

- His origins were in the ‘new unionism’ of the 1880s, where he attacked the conservatism of the union leaders, and its collaboration with liberals and industrialists.

- He believed the Labour Party should be independent.

Morgan then picks out Hardie’s key concerns:

- Unemployment

- Women’s suffrage

- The “defence and advance of democracy”

- Local decision-making[4]

- Colonial liberation

- World peace.

Hardie’s strategy was reform, a gradualism based on “a fusion of political and industrial strategies”. He believed the party should be based on the trade unions, but open to the middle classes and the progressive intellectuals. It had to be a working class party, to give it power, and to properly recognise the needs of its constituency, but it also needed the new ideas, and respectability, of the middle class intelligentsia and its reformers.

This is a difficult mix, very unstable, which can easily fall apart – we saw it happen in the 1980s. Since that decade there has not been a workers’ party, in the accepted sense of the term. In consequence mainstream politics has lost its radicalism: New Labour was never a threat to the new order of financiers and multi-national corporations; and the ever pervasive presence of the United States of America. In his discussion of Hardie, Kenneth O. Morgan picks out something very important:

In so many ways, his ethic was that of the broad church, gradualist, tolerant, solid, subordinating doctrinal divisions to practical action on behalf of specific objectives… At the same time, it is a great mistake to exaggerate Hardie’s respectability or willingness to conform. The contemporary charges of extremism and fanaticism cannot be dismissed as just the accusations of paranoid capitalists contemplating the seeds of their decay…

Hardie never lost sight of the notion that socialism was an ideal, a secular faith. It was not just a matter of pragmatic calculation, technical planning, or managerial techniques. It meant a different kind of society.

Real reformers are visionaries, and they are threats to the rulers and their officers, who will treat them with contempt; fearful of their power. Later, years after they have been effective, they will be sentimentalised. In part because their radical views are now the commonplace.

Thus twenty years after his death and Hardie is beginning to look sedate and conventional; not because his vision and his causes have been left behind, a country road by-passed by the motorway, but because the culture is embracing them, albeit in a different form. In later decades the Labour establishment will talk fondly of Hardie; he has become a myth for them. For they have mistaken the details of his thought, which are now often quite conservative, for the radicalism of his actions and propaganda. Buried in the past he is made safe for Gaitskell, Kinnock and the rest.

Paul Schloss is interested in the interaction between ideas and social forces; and explores this across a number of fields. He calls himself a professional amateur, has worked with housing cooperatives and voluntary groups, and is sceptical of the specialists who cannot get beyond their own, often limited, expertise. He has a blog: serenityscience.blogspot.com

Footnotes

[1] In 1979 there was suspicion right across the political life of Wales: would the rural Welsh speakers be dominated by the English speaking coalfield; or would the latter be ruled by a bi-lingual minority in Cardiff? Language was divisive in 1979. It is less so now, where non-Welsh speakers watch rugby matches with a commentary they do not understand. It is hard, if not impossible, to measure effects like these, but that they must have influence is surely beyond doubt.

[2] Chalmers Johnson’s classic work MITI and the Japanese Miracle explores this in fascinating detail.

[3] Two recent books explore this subject in the United States: Thomas Frank’s The Wrecking Crew; and Susan George’s Hijacking America.

[4] “He was, in the jargon of the 1970s, a devolutionist. He claimed in Merthyr Tydfil to be a Welsh Nationalist, not of course in the sense of Plaid Cymru today, but on behalf of a socialist self-governing Wales, and Scotland and Ireland as well.” (Labour People)

5 Comments

Andy

It may seem odd to say wait and see, but this might be my best answer. There are a few more pieces coming up that deal with how the political gains of one period are eviscerated in the next.

However, I do think there are improvements over time; and I do think than in certain aspects life for just about all British people is better than in 1832 (although what happens in the future…). Politics hasn’t been the sole cause, but it has been a significant factor, in this progressive betterment.

Words like progress are huge abstractions. This essay is much smaller in ambition. I began the piece with a particular idea – how liberal commentators often write off radicals because their immediate goals are defeated. I suggested that this view is wrong, and practical defeat today can lead to cultural change and political victory later; the latter on a narrow front. I was writing about the Chartists, and their very limited political demands. The left has too often agreed with the Liberal spin, but given it a different reading – the heroic defeat. This is usually linked to utopian dreams of systemic change; and a certain millenarianism. I believe this view is a mistake. Rather, we should aim at reform, but our values should be, for want of a better term, radical; thus the example of Hardie.

Later parts of the essay, as you quite rightly say, points to how these (limited) reforms are resisted and later rolled back. You flesh in some more detail. Your image of the rollercoaster is partly correct, but it misses the progressive element in the society – politically in many areas there is regression, but not a total reversion to 1832. Economically and socially there has been vast improvements since the early 19th century, life expectancy one of a number of obvious examples. These are not trivial; although many other gains, you give plenty of examples, are being weakened or removed in this time of reaction.

Your comment about socialist Wales is interesting, and I think highlights the differences between us. I don’t think for one moment that Wales will be either independent or Socialist in my lifetime, if ever. However, I do believe that people who advocate those positions may help bring about positive changes in that country, making it somewhat more responsive to the political and cultural needs of its population; at least in some areas. Too often ideals are conflated with goals. The big vision, which should be an inspiration, is substituted for the small details of political action, and we have failed because Wales has not become socialist. This is the utopian dream; guaranteed for eternal failure. Your comments on changing the rules is true. This is just the point I make in the essay: limited political action today can change the wider culture tomorrow. Although I think the interactions between these are far more complicated than you suggest. For example: “the system” that you mention would include the cultural changes brought about by radical reform. I don’t think it is as instrumentally stable as you think.

Outside left wing thought I don’t know if the working class exists. I was interested in your distinction between the working classes and the ordinary person. I think you are right; but we may disagree on its meaning: the former is a metaphysical concept the latter much more concrete. The implication follows in what you say: those who resist, mostly activists and intellectuals, are distinct from the rest of the society. It is important to recognize this; something the left traditionally has not done. Many implications flow from it. I discuss them at length here – http://serenityscience.blogspot.com/2010/10/hero-worship.html.

Your last paragraph reflects what I think is the main disagreement. A product of historical forces acting at a particular historical period, and which is inevitably transformed over time, is reified into some eternal absolute. Whatever concrete characteristics the working class had in the last two centuries, tied mostly to male employment in heavy industry, would be irremediably transformed by economic and political changes over time; just like about everything else; like the British Empire. Why resurrect a dead beast? Is the class struggle really the motive force of modern history? This is highly debatable, and is almost certainly false. However, this is not to say that the working classes have been unimportant and unnecessary for radical change, thus my reference to Hardie and his belief in a fusion between labour and progressive opinion. Though even here we will need to break things down – it is too easy for us to create an abstraction called the Working Class, and then live in it rather too comfortably.

I often struggle with Walter Benjamin. Too often I’m not sure what he means. If I take your reference to him literally I would have to disagree; at least a little. Of course future generations should take inspiration from the past. And if he means using the short term “defeats” of the previous generation to create victories in the present, well that is exactly the point of my piece. Walter Benjamin agrees with me! I also accept that resistance is ongoing; thus my reference to Colin Leys, and his comments on big business. However, if he believes in the heroic defeat; that all those past movements were failures, that we have to “rewrite” them in our actions of the present I do disagree. I think it is a misreading of history – those “defeats” in themselves may well have helped bring about those later victories; by creating the conditions amenable to reform and radical change.

Essay – Creating the Future: When Conservatives Become Socialists – Ceasefire Magazine

[…] Labour are the temperance campaigners of old who the Chartists so perceptively criticised for avoiding the causes of social injustice. Instead, it embraced them. Peter Mandelson, criticised […]

Essay Creating the Future: Palimpsest – Ceasefire Magazine

[…] essays in the ‘Creating the Future’ series: ‘Victory begins with defeat’ and ‘When conservatives become […]

productos ecológicos para hurones

productos ecológicos para hurones…

[…]Essay Creating the Future: Victory Begins with Defeat | Ceasefire Magazine[…]…

While I agree with the assessment of the Chartists and their long-term effects (and victories) – and would happily extend these to other supposedly ‘failed’ revolutions (e.g. the 1920s-30s and 1960s-70s waves), I have to question the implication of an accumulation of progressive changes and better conditions which is implied here. You seem to be missing the interplay of resistance and recuperation. I think the real dynamic is something like this: faced with radical movements, the elite uses a mixture of concessions and repression. Once the movement is ‘defeated’ (or in remission), the elite seeks to take away the root causes of revolt, redressing grievances. It also seeks to take away the terrain of revolt, blocking opportunities for action and colonising autonomous spaces. Once it is clear that the revolt will not be repeated, the system uses its newly-won impunity to initiate a backlash. It then corrodes as many of the gains of the previous revolt as it can, often in alliance with former radicals who are still celebrating their victories. This continues until a new revolt occurs, often from a new constituency.

It doesn’t seem to me to be an upward slope of progress, but more an up-and-down rollercoaster where victories are often conceded and then dismantled. Hardie’s ideas were successful in modified form in the Fordist-era welfare state, but this welfare state has now largely been dismantled. More recent examples: the Brixton revolt succeeded in the short-term in getting rid of sus laws, and in the medium-term engendered state multiculturalism, but this has now been replaced by a police occupation of marginal communities, a resurrection of sus laws in more comprehensive forms, and a more pervasive state racism under the ‘anti-terror’ banner. The 80s Green movement won big victories (e.g. a moratorium on road building), and was later incorporated into official rhetoric, but official ‘ecological modernisation’ discourse is nothing more than a superficial take on environmentalism subordinated to neoliberalism. Similarly, New Labour adopted the most popular animal rights causes (fox hunting, fur farms) to take the sting out of the movement, before going on a massive offensive of criminalisation of its more central challenges (around vivisection and farming). The workers’ movement won the right to strike, defended it heroically in the 1970s, but lost it in the 1980s. Similarly, the Welsh nationalists did not win an independent, socialist Wales with power for the people; the delayed effect was a neoliberal subsidiarity in which local leaders administer local exploitation. Most crucially, radical movements are rarely simply about particular policy demands – they’re also about ‘who makes the rules’. The system can concede many of the demands, but always keeps a firm grasp on its ‘rule-making’ function, taking the bite out of the reforms it concedes.

I think you recognise this halfway through. The Chartists won on their particular demand (adult male suffrage), but lost on the purpose behind the demand. The idea was that votes for workers would give workers power over the layer which actually ran Britain: Parliament. They received power over Parliament, in return for Parliament no longer running Britain, but only ‘managing’ it. Yet at the start you say, ‘the Chartists won’; the ordinary working person is now feared, instead of the authorities; Chartist radicalism is now ‘common wisdom’, or even a little reactionary (because overtaken by later radicalisms). I’d contend that they didn’t win, though they made things better, and moved the balance of power leftwards for awhile. Rather, the system consolidated, recovered, and counterattacked. Hence, we need to rewrite history as Walter Benjamin proposes, ‘redeeming’ the energies of the defeated in later waves of resistance by ‘winning’ them again later on.

We have full political rights, as long as we don’t want to vote for someone who gets banned as a ‘terrorist organisation’ (cf Batasuna, Sinn Fein, proscribed organisations list). We have gained certain rights, for instance to unemployment benefit, non-discrimination, and to join unions; but we have also lost many of the civil liberties and legal rights which would historically have been recognised (e.g. innocence until proven guilty, right to a jury trial, freedom of association, right to use public spaces without surveillance). And the rights we’ve still got are being constantly corroded to the point of being ineffective in relation to their true purpose (e.g. unions can no longer strike effectively, people are cut off benefits for arbitrary reasons, racism is re-legalised in ‘counter-terror’ laws).

Unfortunately the ‘ordinary person who works hard and pays their dues’ who everyone is meant to fear, is not really the working-class at all, but Sun / Daily Mail readers who hate the non-ordinary (e.g. foreigners, ‘mad’ people) and the non-working (e.g. unemployed people, and in their mind, protesters). Politicians aren’t afraid of taking away people’s benefits, banning strikes, or running down the NHS – they do these things with impunity. Rather, ordinary people who resist capitalism are afraid their overempowered, bigoted neighbour will use the police against them. This corrodes the possibility of forming autonomous spaces among ordinary people, because the system is already inside these spaces.

I’m not really sure as ordinary people have much more power today than pre-1867. Working-class culture was a site of independent culture back then, into which the bourgeoisie had made few inroads. People regularly assembled in huge numbers without state control (for sports, festivals, etc), and could and would fight back militantly if the opportunity presented itself. Most of the technologies of control had not yet been invented – no CCTVs, riot squads, databases, tabloid press, forensics, tasers… the ruling class had a choice between making concessions to movements of resistance, or massacring them and risking an insurrection.

Part of the ruling-class response to working-class power has been to incorporate the working-class through concessions which bring workers into increasing complicity with the state and imperialism. Another part has been to substitute for or infiltrate working-class culture – breaking down its autonomous sites and replacing them with ruling-class voices speaking a working-class language (like the tabloids). Still another part has been to globalise capitalism, so that the site of political contestation – the national level – is no longer the site at which class struggle happens. Yet another part is to attempt to push nationalist and populist identities as alternatives to class (and other oppositional) identities. In fact nationalism, which I suspect is now the dominant ideology, seems to have turned much of the working-class into a reactionary class. So we face a task of trying to repeat struggles with the terrain cut from under us, or follow a path which now has an obstacle placed across it. Finding a way around, over, under or through the new obstacles is decisive for whether we can create another radical wave.