Deportation Cuts: Stories of exile and survival Profiles

Editor's Desk, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Wednesday, August 26, 2020 8:51 - 0 Comments

Over the last two decades, the UK has deported thousands of people to Jamaica. Many of these ‘deportees’ left the Caribbean as infants and grew up in the UK. In my book, Deporting Black Britons, I trace the life stories of four such men who have been exiled from their parents, partners, children and friends by deportation. The book explores how ‘Black Britons’ survive once they reach Jamaica, and what their memories of poverty, racist policing and illegality reveal about contemporary Britain.

Over the last two decades, the UK has deported thousands of people to Jamaica. Many of these ‘deportees’ left the Caribbean as infants and grew up in the UK. In my book, Deporting Black Britons, I trace the life stories of four such men who have been exiled from their parents, partners, children and friends by deportation. The book explores how ‘Black Britons’ survive once they reach Jamaica, and what their memories of poverty, racist policing and illegality reveal about contemporary Britain.

I have been doing research with deported people and their families for nearly five years, and I have used music as a way into people’s complex and painful biographies. In the podcast, Deportation Discs, which uses the format of BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs, I interview deported people, and ask them to present the soundtrack to their lives. In this piece, I hope readers will watch and listen to five music videos that I think help frame these deportation stories (some of the songs were suggested by my interlocutors, some of them are my own selections). This article offers a kind of sonic and visual accompaniment to the book, another way of reading and thinking about stories of violence, exile and survival.

Jason

The first deported person I met in Jamaica was Jason. It was my second day on the island, in September 2015, and we met down at the Salvation Army facility in downtown Kingston. He was full of life, charming and intense, and he spoke with a distinctly East London accent.

Jason’s time in the UK was testing and painful. He was rejected by his mother, and so he had to find ways to survive on the streets. He was homeless for most of the 15 years he spent in London; and he was deported in November 2014 after spending half his life as an ‘illegal immigrant’ with ‘no recourse to public funds’:

You know some of them Christmases there, I’ve slept out in the cold. Some of them Christmases there, I’ve been behind bars, you know. Some of them Christmases there, I didn’t even get to see family, because I had to walk from London to Barking, yeah, to meet my family, and they lived at a different address you know, so, it was really, really upsetting. But I really do miss the festives, and the people, the people are very nice. Genuine people out there.

Jason told vivid, sometimes fantastical, stories about his time on the streets of London. The hustle and the survival, but also always the friendship, the excitement and the possibility. He was subject to everyday racist harassment from the police and the public, was street homeless and sleeping on buses, and was excluded from all social and political rights, but he still managed to make friends and to have adventures, and he came to call the city his home. Whatever had happened, Jason explained, he was ‘glad to have experienced the UK’.

Listening to Hak Baker always makes me think of Jason. They share not only an accent, but an intense love for people of various ethnicities who are differently damaged by poverty, racism and displacement. Jason, too, told beautiful, human stories, with his own kind of poetry.

Now living in Jamaica, Jason cannot speak patois very well. Like Hak Baker, it is obvious that he grew up in East London. He is currently street homeless in Kingston, begging outside Burger King at Half Way Tree. Some people there are nice to him, others are hostile, most ignore him. Perhaps listening to this song, the people he encounters in Jamaica might come to understand his story a little more.

In Conundrum, Hak Baker transports us to “sunny East London”, “the land of the sinners; home of the brave, bold and the winners”, and he recalls the youthful camaraderie – nurtured by boredom, poverty and police harassment – that defined his teenage years. Jason told me that when his mother first kicked him out, aged sixteen, he started selling weed with a white boy from Essex called ‘Fish’. ‘Fish’ used to let Jason sleep on his floor, under his bed, until one morning he was discovered by Fish’s shrieking mother. The story could be straight out of a Hak Baker lyric or video. In conundrum, Baker writes “You’re selling weed to make ya pocket money bigger. The old bill are always locking up my n*ggas. Got the lad’s sleepin’ on London pillars”.

Like Jason, Hak Baker was kicked out of school, out of his family home, and then spent time in prison. Conundrum is a deeply nostalgic song, an ode to youth, to “sunny East London”, before prison and the heaviness of adulthood. Like Jason’s descriptions of his teenage years in London, the lyrics capture a certain kind of freedom, where “everyday was a laugh”, friends “all in it for the love of shenanigans”. While Hak Baker was not deported, the song nonetheless harks back to a time that cannot be returned to, and to a freedom that cannot be restored.

Ricardo

Experiences of racist policing were central to the stories people told me about how and why they were deported. In multi-status Britain, racism in the criminal justice system now leads to deportation, and this has particularly weighty consequences for young black men.

Ricardo’s experiences with racist policing were especially shameful. He moved to the UK when he was 10, and lived in Smethwick, in the West Midlands. By the time he was 14, the police became a regular and overbearing feature of his life:

I was arrested over 100 times and always NFA’d [no further action], never charged. The police used to just come on the park, and everybody would run. They used to hassle me differently fam, always arresting me for no reason.

Ricardo explained that he was ‘just always getting arrested for robberies’. He began to feel that he could not leave his house without being harassed by the police. He explained that Friday nights were the worst, because if he was arrested then, the police could hold him over the weekend without charging him. The police set up a camera directly outside Ricardo’s house, which faced the front door, apparently to deal with ‘anti-social behaviour’, and Ricardo and his friends told me that the police used to ‘kick the front door in’ when looking for his brother.

This is what heavy, disproportionate and racist policing in the UK looks like – the denial of basic democratic rights: access to public space, freedom of association and to the presumption of innocence. Ricardo was also wholly denied access to the protections typically conferred by childhood, a denial made possible by the force of anti-black racism.

In light of his account, I asked Ricardo if he would like to go back to the UK at some point and he said, ‘Of course, yeah, but I would stay away from the West Midlands. If that’s how the police treated me before I even did anything, just imagine now.’ In 2017, Ricardo posted a song by Mulla Ess on his Facebook wall. In “F the Feds”, Mulla Ess raps with a distinctly West Midlands accent, delivering a sharp critique of racist policing and the incarceration of young people. Neither the song nor the artist are particularly well known, but I have heard no other lyrics that better capture what Ricardo and his friends told me about the intensity of racist state violence as they experienced it. As Mulla Ess puts it in a particularly haunting bar: “So fuck the witness, and the statements. And fuck the G4S staff I think they’re racist. They had me sleeping on the floor up on basic. Now tell me at 14 could you take it?”

Denico

Deportation means violently separating people from their homes, their families, their friends and their memories. This violence is about more than forcing people onto planes, it’s about exiling them from their loved ones and preventing them from returning through the technologies of passports, biometrics and databases.

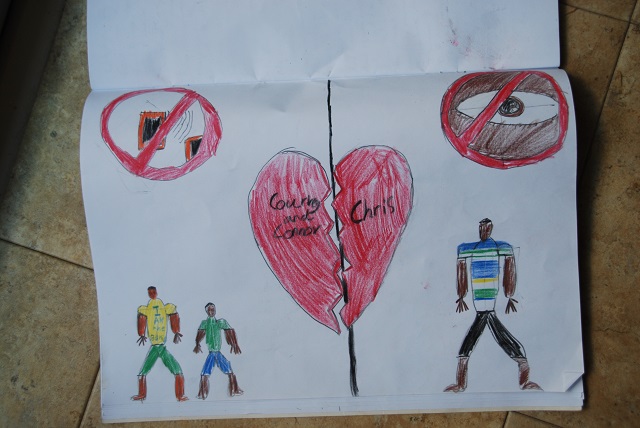

Denico moved to the UK when he was 13, and lived in the UK until he was 26. Before he was arrested for selling drugs, which he sold because he was an ‘illegal immigrant’ excluded from the ‘right to work’, Denico was building his life with Kendal, and her two daughters Maisy and Tamara – all three British citizens. They were separated first by prison and then by deportation, which proved final.

When Denico returned to Jamaica, in 2015, he burnt the legal documents he had carried with him and it is not hard to see why. There was no way for him to articulate what his relationships meant to him – the love he felt for Kendal, Tamara and Maisy – and his submissions to the Home Office were treated with scepticism and derision. Deportation proceeds not only through assertions of criminality and illegality, then, but also in relation to ‘family life’. People are deported in spite of family connections, and through the denigration and devaluing of lived family relationships. To justify deportation, normative ideas about gender, sexuality and ‘the family’ are enforced in profoundly restrictive ways: step parenthood counts for less than biological parenthood, the care work provided by fathers counts less than that of mothers, and relationships ‘akin to marriage’ are the only ones recognised between partners.

Denico is an extremely gentle and sentimental man, and he connected his own story to those of other deported people in his situation. When I told him about Cashh, the UK rapper who was removed in 2014, just a year before Denico, he began listening to his songs and watching his videos, especially the ones he released in Jamaica. Cashh is now back in the UK – after five years in Jamaica he won his appeal and was able to return. Denico, meanwhile, now has a daughter in Jamaica. The Removal, by Cashh, perhaps captures a different time in both men’s lives, but it is a song that still resonates with Denico as he processes what has been done to him.

Chris

When deported people return to – or rather arrive in – Jamaica, they must find ways to survive in an unfamiliar place. British ‘deportees’ are often stereotyped by locals as ‘criminals’, and described as individuals who had a ‘golden opportunity’ and wasted it. They often struggle to reconnect with estranged relatives, and this can lead to homelessness. In the context of poverty and social isolation, deported people are also exposed to serious violence. Chris, another deported person who spent roughly half his life in the England, having left Jamaica at fourteen, recalled his experiences of homelessness in the first year after he returned.

I’m sleeping on the floor, and my uncle is, like, ‘Bwoy, if police or gunman come look for you, I don’t want them to come in my house’. And I’m like, ‘But nobody’s gonna come look for me. I just ain’t got nowhere to go because I fell out with my cousin out there, and I’m lost right now. I just need a little bit of understanding, a little bit of support.’ He didn’t give me nothing.

After being kicked out of his uncle’s house, Chris had nowhere to go and no one to call on. He walked aimlessly up Windward Road towards ‘town’, and by chance stumbled upon Open Arms Drop in Centre – a homeless shelter with bed spaces for deported people. After speaking with the management he was able to secure a bed space in the large dormitory. This would be his home for the next seven months.

Chris found work here and there, and built friendships on the street where he grew up, in Rockfort, East Kingston, but life was tough. Often he did not eat at all in a given day, and he was sleeping on a friend’s floor for some months. On one occasion, the police forced him to the ground and held a gun to his head, after accusing him of being a ‘deportee’ who had ‘come back from foreign’ and bought firearms for his friends. Still, he was surviving.

Chris’s experiences of state violence, extreme poverty, chronic underemployment, and strained relationships with family members were all fairly typical of the ‘deportee’ experience. That said, while deported people like Chris experience these hardships specifically in relation to their exclusion from the UK, they are not the only people in Jamaica who are poor, hungry, and constrained by violence. Nor are they the only Jamaicans who are immobilised and fixed in place, fenced out of countries where there are greater opportunities, higher wages and better living conditions. Frustrated and restricted mobilities are the stuff of Jamaican citizenship.

In this light, Chris’s return to Jamaica was not only defined by exile from the UK, but also by a kind of reinsertion into the ‘ghettos’ of Kingston. Vybz Kartel, in his track ‘Money Mi A Look’, skilfully describes the poverty, immobility and resourcefulness among Jamaica’s poor, a group whose ranks Chris was joining.

The world does not stand still, and yet writing relies on pressing the pause button somewhere. This means that the portraits in my book are inevitably incomplete and out of date. Despite this, in a book-length account of deportation it is possible to capture the contradictory and unfinished character of people’s lives. In shorter and more politically motivated writing, it is easy to overstress the desperation, the hopelessness and the isolation faced by deported people, as though the world stops when their deportation flight lands. It does not.

For Jason, Ricardo, Chris and Denico, exile is a process. Yet there is hope, even if a sad kind of hope, in the recognition that they and others like them have survived. Most people find a way to keep going. The ability of deported people to survive and rebuild does not make deportation any less cruel, but it does offer hope. As Ricardo put it: “If I didn’t let incarceration break me, I’m not gonna let freedom break me. Wherever you put me, I’ve got freedom.”

The life stories of Jason, Ricardo, Chris and Denico testify to the violence of immigration control, reminding us of what we are up against, but they also remind us that, amid the damage of racism and nationalism, there are always connections being built, friendships being made and boundaries being crossed. Perhaps ‘deportees’, like all exiles, can offer some pointers on how to live together differently. As Edward Said puts it in his Reflections on Exile:

The exile knows that in a secular and contingent world, homes are always provisional. Borders and barriers, which enclose us within the safety of familiar territory can also become prisons, and are often defended beyond reason or necessity. Exiles cross borders, break barriers of thought and experience.

Michelle

When I interviewed Michelle for my podcast Deportation Discs (like BBC’s Desert Island Discs, but with deported people), she wanted to end our conversation on a positive note. Despite being separated from her partner and step-children, and then missing her mother’s sudden death and funeral in the UK, Michelle emphasised her agency and determination to make something of her life in Jamaica.

I’ve accepted that I’m here, and I’m trying to better myself. England is not the only country in the world, so I am staying focused. Who knows what might happen. I miss my step kids, my partner, my mum, but I am learning to accept things as they are. This song by Koffee is the best one I can think of for where I am right now. Blessings come in different forms.

Michelle is due to have her first child in early September. Blessings come in different forms, and ends can also be beginnings.

Deporting Black Britons: Portraits of Deportation to Jamaica

Deporting Black Britons: Portraits of Deportation to Jamaica

320pp

Manchester University Press

Publication Date: September 2020

Leave a Reply