Review | ‘Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War’ Books

Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Tuesday, March 1, 2016 8:27 - 0 Comments

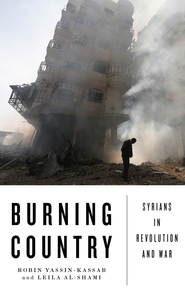

![A Syrian man carries a girl amidst the rubble of houses in Aleppo, Syria [Source: AP]](https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Aleppo-Ceasefire-Magazine.jpg)

A Syrian man carries a girl amidst the rubble of houses in Aleppo, Syria [Source: AP]

Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War

Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami

Paperback: 280 pages

Pluto Press (Jan 2016)

When it comes to Syria, the old adage proves poignantly true: there is no time like the present. As a flaky truce hangs over the tattered remains of this land, Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami bring us a timely and searing account of the people who have shaped the events of the past few years.

This was undoubtedly not an easy task. None of the other countries affected by the Arab Spring of 2011 have provoked as much bitter debate and division across the globe than Syria. Combatants, aid workers, journalists and war tourists – from the West Indies to Japan, and from Los Angeles to Moscow – have, knowingly or otherwise, taken sides in the conflict, and converged on this small and relatively unknown country to take part in a conflict that is dismissed by many as too “complex” or tragic to comprehend. And yet, Yassin-Kassab and Al-Shami have done a remarkable job of creating an approachable, highly readable, and deeply human account of how the Syrian people themselves viewed the revolution and its aftermath.

The book consists of ten chapters, followed by an epilogue, and assumes no previous knowledge of Syria or the Syrian revolution. Like most books about the country, we start in the past, and work our way towards the painful present as events unfold with the grace of a car crash watched in slow motion.

Though an ancient land, Syria is in many ways a new country; its young people weighed down by the burden of a history they struggle to understand and have yet to come to terms with. What the book doesn’t do is give a breakdown of the nebulous network of military factions and alliances operating within the country. Where these are mentioned, it is to elucidate their relationship with the revolution as it was experienced from a civilian perspective. It is a book about people in a time of revolution.

To say that the Syrian revolution is a product of the Assad regime’s rule is an understatement, and here the authors perform an admirable job of surveying the crucial decade leading to the 2011 revolution, during which Bashaar al Assad’s regime was liberalising the country’s economy, and parcelling off large parts of the economy to his family and cronies.

Nobody, least of all Syrians, could have expected that a revolution was going to erupt in 2011. In fact, Assad was so confident that he would avoid the unrest facing other Arab dictators that he told a German newspaper weeks before the first protests that his rule was safe owing to his alleged anti-imperialist foreign policy stances.

Within weeks, the slow trickle of protests in the Spring of 2011 turned into a deluge. Nobody expected the explosion of community spirit and activism that erupted, overwhelmingly composed of young people. Syrians young and old were finding that they had a voice, and were organising into what would later become the “Local Coordination Committees”.

Today, it is easy to be cynical amidst the thousands of fighting groups and pretend there is no political alternative to the Assad regime. But here Yassin-Kassab and Al-Shami remind us of the young men and women who broke all economic, cultural, social and gender barriers to create a new Syria. We are told about inspiring people like Yassin Haj Saleh, Razan Zeitouneh, and the erudite Omar Aziz – a remarkable man who was instrumental in the formation of the Local Coordination committees before dying a prisoner of the Assad regime.

The people whose imagination and indignation were fired by the protests against Assad’s clumsy and brutal rule may have been slightly naive, and possibly doomed to fail, but they created an all important wedge that has already made it impossible for the regime to rule Syria the way it had done since 1970.

The picture we are presented with is one of idealistic youth, betrayed and ignored by the world, fallible yet courageous, and capable of remarkable altruism against overwhelming odds. The authors introduce us to young activists who loved, lived and fought for ideals that the world cared little for. The Syria he shows us is not the caricatured Jihadi paradise littered with armed groups that most political pundits would have us think (though that is important).

The chapter on the rise of Islamisms is poignant and tells us much about how ordinary Syrians viewed the phenomenon. We are given an insight into the debates Syrian activists and revolutionaries have been conducting, ones that continue to be tackled within the various corners of Syria’s opposition, on the role of religion in the revolution and the state, on gender, on the treatment of prisoners and the rules of war, and even on whether or not the revolution should have become an armed one.

The “official” Syrian opposition, in its various iterations and factions, is painted (deservedly) in a rather unfavourable light, and its story is one of folly, pettiness, and narrow-minded scheming in the face of a relentless and focused regime.

Crucially, the issue of sectarianism is dealt with frankly. For a country like Syria, where sectarianism was always bubbling beneath the surface and yet quietly ignored, it was perhaps inevitable that a revolution would bring the tensions to the surface. Here, Yassin-Kassab and Al-Shami are at pains to show that while the Alawites as a minority might have sided – mostly out of fear – with the Assad regime, a vocal and very important minority within that minority spoke out in favour of the revolution from its early days. Actors such as Fadwa Suliman, as well as activists in Syrian cities like Lattakia, were instrumental in building relationships between communities to alleviate fears in the face of “shabeeha” provocation.

The authors show that the Syrian revolution, like the country that birthed it, had a thousand mothers, and came in all shades. It was, one could argue, the real beating heart of Syria, long dormant under the Assad regime, and briefly exposed to the world in all its glorious contradictions. That the revolution was ultimately ignored, buried, and then forgotten amidst the media cacophony over radical Islamism and civil war, speaks more of the world’s lack of imagination and understanding than any lack of ingenuity amongst the Syrian people themselves.

Through no fault of their own, the flower of Syria’s youth has been sacrificed, either on the altar of the revolution or drowned in the Mediterranean trying desperately to escape the killing zone their country had become. Others linger on in exile, losing all hope of return, whilst the international community wrings its hands and dithers in the face of overwhelming support for Assad by his Russian and Iranian allies.

Through no fault of their own, the flower of Syria’s youth has been sacrificed, either on the altar of the revolution or drowned in the Mediterranean trying desperately to escape the killing zone their country had become. Others linger on in exile, losing all hope of return, whilst the international community wrings its hands and dithers in the face of overwhelming support for Assad by his Russian and Iranian allies.

Burning Country isn’t just the story of the Syrian revolution the way Syrians saw it, but a testament to the efforts and dreams of a generation of Syrians in a unique period of this region’s history.

Robin Yassin-Kassab will be in conversation with Wassim Al-Adel on March 1st, 2016 at Waterstones Picadilly. For details visit the event’s page.

See also: Robin Yassin-Kassab: Syria: Blundering and Adapting

Leave a Reply