A historic milestone or the beginning of the end for the student movement? Quebec Chronicles

New in Ceasefire, Quebec Chronicles - Posted on Tuesday, September 11, 2012 0:00 - 0 Comments

Pauline Marois, on the day after she was elected Premier of Quebec.

On Wednesday night, the Quebec electorate gathered in front of television sets to watch the results come in from the provincial election they had voted in earlier that day. The vote, which followed a month-long campaign, was a chance for Quebec to decide what direction to take for the future, following this spring’s printemps érable (Maple Spring) mobilization.

Along Montreal’s Avenue Mont-Royal, friends and neighbours packed into bars to watch the action and let out cheers as they learned that Jean Charest, the Quebec Liberal Party leader who has been Quebec’s premier for the past nine years, was voted out of office, failing to even win his own riding. In his place, Pauline Marois of the Parti Québecois (PQ) has become Quebec’s first female premier, but her party fell nine seats short of a majority in Quebec’s National Assembly, a sure obstacle to the fulfillment of her campaign promises.

The election, which has been called “disappointing for everyone involved”, took a disturbing turn when, outside the PQ’s victory party, a gunman shot one man dead and wounded another in an apparent political assassination attempt.

The Vote

At the polling booth, Quebecers had a choice between three major parties and two minor ones, their ideologies spread over double axes: sovreigntist-federalist and left-right. On one end, Charest’s center-right, federalist liberals competed with François Legault’s Coalition Avenir Québecois, a pro-business, nationalist-not-sovereigntist upstart that divided the right-wing vote.

The Liberals’ perennial rival (no other party has won an election since the sixties), the Parti Québecois, is a coalition itself, its members resting on both sides of the left/right divide. The PQ’s main objective is for Quebec to become a sovereign country. It has a mostly centrist platform, but can lean left on some issues, such as Marois’ campaign promise to pay for the abolition of Quebec’s $400 flat-rate health tax by raising taxes on the wealthy.

Left of center, the PQ splinter party Option Nationale promised social democratic economics and , but failed win any seats. The far-left Québec Solidaire, whose co-spokesperson and only deputy Amir Khadir was arrested for taking part in an illegal student protest this summer, won a small victory when its other co-spokesperson, Françoise David, won in Montreal’s Gouin riding after a strong performance in the leaders’ debate.

Because of the threat to the PQ’s success posed by these two small parties, strategic voting was the subject of intense debate throughout the month, and somewhere around the middle of it, the PQ launched its “Je vote majoritaire” ad campaign, saying that only a majority win could allow them to. Although it’s small comfort to anyone, it was revealed in post-election analysis that, if the votes for ON and QS were added to the PQ’s tally, they would have ensured a majority in Quebec’s national assembly.

The end of the student movement?

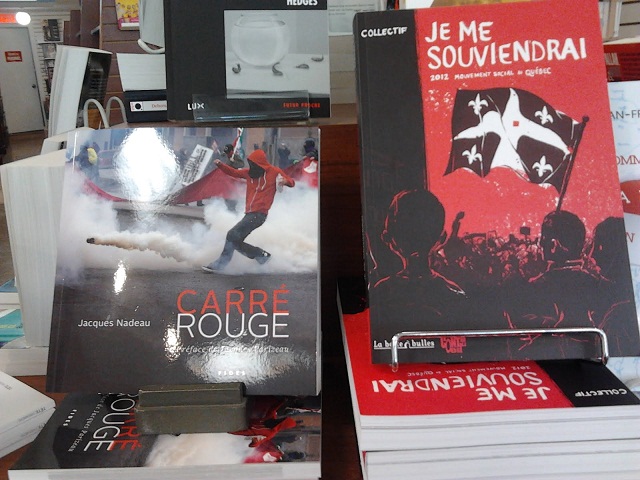

Student Movement retrospectives in a Montreal bookstore.

Three books about the Quebec student movement have been published to date, contributing to the growing feeling that it’s passing into history. Mobilization lagged over the summer, and the movement’s most famous face, Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, has stepped down from his role as co-spokesperson for the student federation CLASSE, citing the “need for fresh faces.” The forced return to classes under Charest’s loi spéciale (an event accompanied by heavy police presence) caused some clashes at Université de Montréal and UQAM last month, but with most student associations having suspended their strike for the duration of elections, students have been able to complete their winter semester and receive credit, although catchup has caused many a pedagogical and administrative headache.

A graphic from UQAM’s Faculty of Arts student association reads: “together, we stopped the hike.”

The results of the election, as well as Pauline Marois’ promise to abolish tuition fee hikes by ministerial decree (something she can do without the support of the opposition), are the closing of a chapter for the student movement and its supporters, whose slogans insulted Charest as often as they denounced his hikes. Many of these printempistes, see the liberals’ ousting as a clear victory.

The FECQ and FEUQ student federations made headlines last week by asserting that the student conflict, in their view, was “over” because of the results of the election, adding that now was the time to work with the new government, whom they would give a fair chance.

There are obstacles ahead. The PQ won’t have an easy time abolishing Charest’s anti-strike “loi spéciale”, and will for budgetary reasons have to cut the raise in financial aid benefits, made by the Liberals in the hopes of appeasing students last spring. The challenge of funding Quebec’s universities while keeping fees frozen is still far from being addressed, and the PQ’s plans for a summit on universities is seen by many as an ambiguous solution.

Pauline Marois’ record on tuition is not altogether clean: though she wore the student movement’s red square in parliament this spring (but removed it before the campaign), she attempted to de-freeze tuition as education minister in the nineties. Lately, she favours indexing tuition to the cost of living.

CLASSE, known as the most radical of the three student federations, is strongly against indexation, and has decided to continue the fight into the fall, this time with a focus on free education. It is planning another National Demonstration on September 22nd. With students back in class. the matter of whether a significant number will mobilize around this issue to exercise sufficient pressure is by no means certain.

The student movement’s status may be unclear, but its impact on the elections was remarkable. Although some deplored the candidates’ lack of willingness to address the deeper issues raised by the Maple Spring (any debate on the “bien commun”, the student’s rallying cry that “re-ignited” Quebec’s left, was largely missing from the campaign), the tuition hikes issue was prominent. Additionally, voter participation shot up 15% from 2008, perhaps due to the fact that youth now have, as sociologist Jaques Hamel told Le Devoir, “a larger interest in politics […] because they see how a government can act against them.”

The Liberals may no longer be in charge, but between their remaining deputies and the CAQ’s, right-leaning parties dominate the legislature, and the PQ’s ambitious linguistic and fiscal promises, like abolishing the province’s flat-rate health tax the and restricting access to English cégeps, are likely to fall by the wayside, just like her plans to hold a third referendum on Quebec sovereignty.

An act of violence

It has been hard for anyone here to make sense of the actions of Richard Henry Bain, the gunman who cried “the English are awakening” in accented French after he fired the shots that killed one man and wounded another outside Pauline Marois’ victory speech in downtown Montreal.

The PQ shooter under arrest on election night. (Photo: La Presse)

The Montreal Gazette, bastion of the city’s minority anglophone community, ran an editorial entitled “An act of violence unrepresentative of Quebec”, in which it argued that the isolated actions of a deranged individual cannot speak to the true nature of anglophone-francophone relations in the province. The following day, Le Devoir took a different stance, publishing commentary from the Saint Jean Baptiste Society, who said that a “sociopolitical trigger” was present in the attacks and calling for Canadian media (The Gazette included) to stop their “demonization” of sovereigntists.

To add to the disappointment, it soon became clear that if international audiences heard anything about the election, it was likely in the context of the shooting.

Leave a Reply