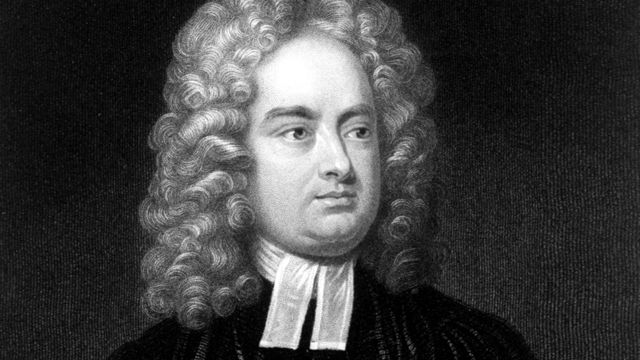

Jonathan Swift: icon of 2011? Arts & Culture

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Thursday, December 29, 2011 19:10 - 0 Comments

This week, Newt Gingrich, current favourite in the Republican presidential race, suggested the reintroduction of child labour, prompting a Guardian commentator to ask: are we going back to the 18th century? Times of crisis tend to encourage comparisons with the past, for comfort or otherwise. The most obvious precedent – the Great Depression – has been endlessly discussed since the 2008 crisis. More recently, a study finds current wage disparity in Britain ‘worse than Victorian levels’. With the prospect of EU meltdown, yet more ‘shared pain’, the replacement of most of Europe’s leaders with unelected technocrats – in short, with everything bound to get even worse – one wonders how far we’ll soon have to look back to find a suitably unfortunate parallel for our times.

Let’s stick for now with the 18th century. A recent Mother Jones article humorously captured the new Enlightenment vogue, taking inspiration from Jonathan Swift’s famous pamphlet ‘A Modest Proposal’ to suggest a gathering on Wall Street of the 99% – who are to offer up in ritual sacrifice to late capitalism their college degrees, housing deeds, children. But is there anything else we can take from a comparison with Swift – and not just from his anarchic spirit and graveyard humour, but from the specific circumstances that produced his Irish pamphlets?

*

Swift had been occasionally writing on Irish politics since 1707, but the real tipping point, when he fully assumed the mantle of ‘Hibernian Patriot’ and entered nationalist mythology, came in 1724. That year an obscure English ironmaster named William Wood obtained a patent from George I to privately mint £100,000 worth of copper halfpence for Ireland. The scheme, dubbed ‘Wood’s halfpence’, would have glutted the Irish economy with inferior coin, devaluing Irish manufacture and assets. In Ireland, already resentful about England’s severe economic restrictions (which included, ironically, a ban on minting currency) , the proposal met with widespread anger. Under the nom de plume of ‘The Drapier’, and heavily influenced by John Locke, Swift addressed a series of letters to the Irish people, advancing a systemic condemnation of colonial policy in Ireland and inciting resistance.

Swift’s arguments were understandably less popular in England than in Ireland. His first published political tract, the 1720’s ‘Proposal for the Universal Use of Irish Manufacture’ , which advocated the refusal of English imports (‘I should rejoice to see a Stay-Lace from England be thought Scandalous’, etc.) so enraged the English authorities that its printer, John Harding, was prosecuted. On the publication of the Drapier’s fourth letter – by a long chalk his most revolutionary, challenging the fundamental tenets of Irish dependancy – the English-installed Lord Lieutenant Carteret offered a reward of £300 for the identity of the Drapier. No-one came forward. Meanwhile, Wood waged a campaign of misinformation in England, producing pamphlets that claimed universal support for the half-pence among the Irish, with dissent confined to a manipulative cadre of ‘Papists and enemies to King George’.

Swift’s arguments were understandably less popular in England than in Ireland. His first published political tract, the 1720’s ‘Proposal for the Universal Use of Irish Manufacture’ , which advocated the refusal of English imports (‘I should rejoice to see a Stay-Lace from England be thought Scandalous’, etc.) so enraged the English authorities that its printer, John Harding, was prosecuted. On the publication of the Drapier’s fourth letter – by a long chalk his most revolutionary, challenging the fundamental tenets of Irish dependancy – the English-installed Lord Lieutenant Carteret offered a reward of £300 for the identity of the Drapier. No-one came forward. Meanwhile, Wood waged a campaign of misinformation in England, producing pamphlets that claimed universal support for the half-pence among the Irish, with dissent confined to a manipulative cadre of ‘Papists and enemies to King George’.

Remarkably, The Drapier and Ireland won out. Manifestly and unavoidably rejected by the majority of Irish people – and in the final instance by the Irish Grand-Jury – the English Government were forced to withdraw the proposal, compensating Wood with a big pension which, ever luckless in business, he would squander on a half-cocked experiment with iron patents. Swift – Dean, Drapier, Hibernian Patriot – entered the annals of Irish nationalist mythology, as eulogised by Yeats: ‘World-besotted traveller he/Served human liberty’.

The Drapier’s Letters and related tracts wittily chronicle a lurid and scandalous episode of British colonialism , and represent a vital landmark in Irish nationalism and the development of anti-colonial thought. They also speak, with unusual precision, to a very current moment in resistance.

Consider, for example, Swift’s statement in ‘A Short View of the State of Ireland’: ‘I have sometimes thought, that this Paradox of the Kingdom growing rich, is chiefly owing to those gentlemen the BANKERS, who are the only thriving people among us.’ The enemy in Swift’s pamphlets – whether it is refracted through bankers, landlords, financial speculators, the colonial English – is always the ‘one percent’. Wood and his half-pence, after all, comes down to a private financial interest in bed with government, a neoliberal game of speculation and a ruined population with no recourse to democracy.

‘A Modest Proposal’, the perfect summation of Swift’s dissident consciousness, suggests that an impoverished native population sell its children as food for rich landlords, removing the problem of an unproductive element in society and providing a lucrative home-grown industry in one fell swoop. Swift, adopting the voice of a ‘Projector’ (in modern parlance, a technocrat) carries the irony to its logical extreme: ‘Whereas the maintenance of an Hundred Thousand Children cannot be computed at less than ten Shillings a piece per annum, the Nation’s stock will be thereby encreased Fifty Thousand Pounds per annum; and the Money will circulate among our selves, the Goods being entirely of our own Growth and Manufacture.’

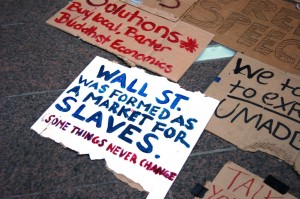

Swift’s Irish pamphlets render monstrous these abstractions of economic logic. Maxims and economic rules are controlled and defied by Ireland, which – due to the imbalances of colonial rule – represents a sort of a ‘nonsense state’, where accepted truths about prosperity and growth go to die. Economic wisdom dictates, ‘The people are the riches of a nation’; only, Swift corrects, ‘if we had the African privilege of selling our bodies as slaves’ since the native Irish, rendered beggars by colonial restrictions, are worth no more than their weight in flesh. In 2011, the maxims that underwrite prosperity in the neoliberal age – minimal regulation, ‘free’ markets, cheap credit, an undemocratic economy tightly controlled by an isolated financial sector – increasingly assume the quality of the absurd. The role of protest in such conditions often becomes, as Swift famously discovered, the use of satire, parody, and reductio ad absurdum. And for both Swift and the 2011 resistance, it is the clinical absurdity of classical economic thinking that has formed the target of such satire.

Swift’s Irish pamphlets render monstrous these abstractions of economic logic. Maxims and economic rules are controlled and defied by Ireland, which – due to the imbalances of colonial rule – represents a sort of a ‘nonsense state’, where accepted truths about prosperity and growth go to die. Economic wisdom dictates, ‘The people are the riches of a nation’; only, Swift corrects, ‘if we had the African privilege of selling our bodies as slaves’ since the native Irish, rendered beggars by colonial restrictions, are worth no more than their weight in flesh. In 2011, the maxims that underwrite prosperity in the neoliberal age – minimal regulation, ‘free’ markets, cheap credit, an undemocratic economy tightly controlled by an isolated financial sector – increasingly assume the quality of the absurd. The role of protest in such conditions often becomes, as Swift famously discovered, the use of satire, parody, and reductio ad absurdum. And for both Swift and the 2011 resistance, it is the clinical absurdity of classical economic thinking that has formed the target of such satire.

*

Colm Toibin, in a recent LRB panel discussion, likened Swift Irish pamphlets to a ‘blog’. It’s an interesting and, in many ways, valid comparison. Pamphlets provided Swift with a free channel of communication – an uncensored format that was cheap, anonymous (or, in his case, pseudonymous) that enabled him to respond quickly to developments in the unfolding drama of the ‘Wood affair’. Pamphets offered, like the Internet does now, a democratic alternative to the metropolitan media engine. ‘My people wanted’, writes the Drapier, ‘a plain, strong, coarse stuff, to defend them against cold Easterly winds’, and indeed, his pamphlets reflect this self-effacement, privileging maximum exposure – ‘one copy of this paper may serve a Dozen of you, which will be less than a Farthing apiece’ – over artistic posterity, or profit. This year’s revolution – which has definitively not been televised – has mobilised an efficient, potent counter-narrative through digital media channels, outflanking a mainstream media establishment debased by corporate and state interests. ‘The Kingdom requires New and Fresh warning,’ observes Swift, ‘since Wood is his own News-Writer’: a sentiment that resonates loudly in the age of News International.

In a recent New York Review of Books article, Michael Greenberg tried to sum up the Occupy Wall Street mentality: ‘a galvanising succinctness, speaking directly’, he offered. It is a description that precisely fits Swift’s criticism of financial capitalism in the Drapier’s Letters, which was reactive and populist, attuned to the universal, basic and concrete realities of injustice. It is tempting (almost irresistible, with ‘Proposal for the Universal Use of Irish Manufacture’) but ill-advised to read a proto-Marxist vein into some of his pamphlets. Swift wasn’t a socialist or a revolutionary, nor indeed, on close examination, much of an egalitarian – he revolted on a moral and instinctive, rather than a political, level against a cluster of injustices at a particular place and time. But it is precisely this ambivalence and occasionality that could be said to characterise the mood of protests in 2011: notably, of course, the Occupy movement, which has seen a return to a discourse of protest that relies on notions of instinctive injustice. And it may well be the case that in 2011, as Swift wrote in his fourth letter: ‘Money, the great divider of our world, hath, by a Strange Revolution, been the great Uniter of a most Divided people.’

In a recent New York Review of Books article, Michael Greenberg tried to sum up the Occupy Wall Street mentality: ‘a galvanising succinctness, speaking directly’, he offered. It is a description that precisely fits Swift’s criticism of financial capitalism in the Drapier’s Letters, which was reactive and populist, attuned to the universal, basic and concrete realities of injustice. It is tempting (almost irresistible, with ‘Proposal for the Universal Use of Irish Manufacture’) but ill-advised to read a proto-Marxist vein into some of his pamphlets. Swift wasn’t a socialist or a revolutionary, nor indeed, on close examination, much of an egalitarian – he revolted on a moral and instinctive, rather than a political, level against a cluster of injustices at a particular place and time. But it is precisely this ambivalence and occasionality that could be said to characterise the mood of protests in 2011: notably, of course, the Occupy movement, which has seen a return to a discourse of protest that relies on notions of instinctive injustice. And it may well be the case that in 2011, as Swift wrote in his fourth letter: ‘Money, the great divider of our world, hath, by a Strange Revolution, been the great Uniter of a most Divided people.’

Swift remains, despite all this, a problematic touchstone for radical activism. Recent critical examinations of the ‘Hibernian Patriot’, notably by Carole Fabricant and Robert Mahony, have corrected for and nuanced the stock image of Swift as anti-imperialist hero. His political tracts, while directed ‘To the Whole People of Ireland’, must be understood as coming from a writer who was, however precariously, part of the Protestant elite in colonial Ireland. For all his sustained engagement with subordinated classes – and it is not to be disregarded as just ‘token’, or ‘rhetorical’ – his efforts on behalf of the most marginalised segments of colonial Irish society are often paternalist, a negative defence.

For example, he challenges discrimination and repression of Irish Catholics – a seditious, murderous third column in the Protestant imagination – by emphasising their political toothlessness: ‘A Lyon at Feet, bound fast with three of four Chains, his Teeth drawn out and his Claws pared to the Quick’. Nowhere in his writing is the possibility of equality between Protestants and Catholics seriously entertained.

Even Swift’s pivotal anti-colonial tract, A Modest Proposal, is qualified by some apparently earnest genocidal tendencies elsewhere in his writing. In the aforementioned ‘Maxims Controlled in Ireland’, he confesses himself ‘touched with a very sensible pleasure, when I hear of a mortality in any country parish…[populated by] wretches, brought up to steal and beg, for whom death would be the best thing to be wished for.’ For all Swift’s mockery of inhuman Projectors, the Irish poor appear in his writing as a sub-human, inherently criminal undercaste, a burden on society, ‘bred up from the Dunghill in idleness, Ignorance and Thievery’ and undeserving of sympathy or charity and owing their poverty to their own natural defects. There is an unavoidable reactionary strain in Swift’s writing and he must, despite his unusual applicability to contemporary patterns of resistance, always be read with the particular circumstances of his time and situation – his ‘hyphenated Anglo-Irish identity’ – in mind.

If the state of popular resistance in 2011 tells us anything it is – to go back yet further in time, to Trinculo in The Tempest – that ‘misery acquaints a man with Strange Bedfellows’. The financial crisis has broadened the definition of the protester. Some sectors of the traditional left who would, one suspects, prefer a picturesque revolution in the Marxist tradition, baulk at the populism of the movements like Occupy, which counts among its martyrs Scott Olsen (an ex-marine and Iraq war veteran), or the role of Islam in post-revolution Egypt. Swift’s Irish writing is ambivalent, problematic and paradoxical – in other words, perfect reading for a year of uncomfortable dissent.

Leave a Reply