Radical Aesthetics The Myth of Mad Tracey

Arts & Culture, New in Ceasefire, Radical Aesthetics - Posted on Saturday, August 20, 2011 0:00 - 2 Comments

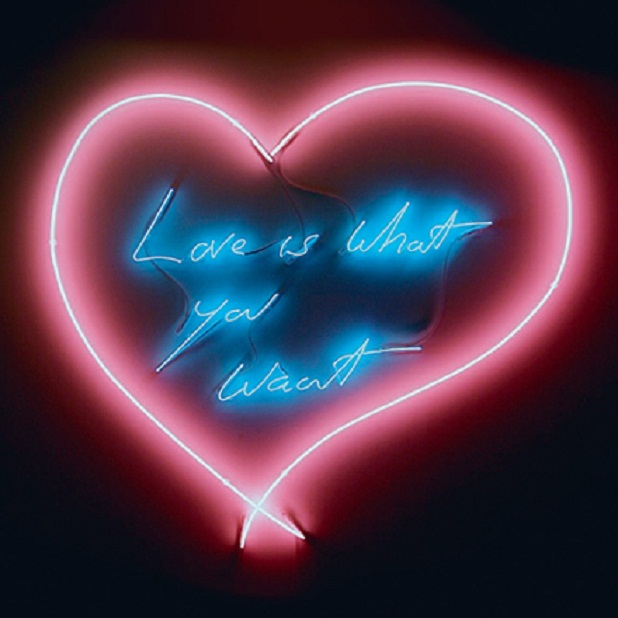

Tracey Emin, Love is What You Want, 2011, ©Tracey Emin Photo Kerry Ryan

By Daniel Barnes

The harrowing and yet majestic experience that is the Tracey Emin retrospective at the Hayward Gallery is a comprehensive survey of twenty years of work that presents a seemingly relentless barrage of desperation, loneliness and outright anguish. But the existentially crushing hopelessness of it all is slowly diffused by the realisation that Emin is worth the hype and has earned her place in art history.

In the final analysis, the exhibition demonstrates Emin’s singular talent for transfiguring life into art without obscurity or sentimentality. It reveals Emin’s profound sensitivity to how materials can convey meaning and her refreshing transparency. The work is actually infused with love, even if it is sometimes hard to find, giving it a visceral immediacy and aesthetic value that can only arise from careful manipulation of a pervasive mythology.

There is an apocryphal story that the title for Emin’s 1997 South London Gallery show, ‘I Need Art Like I Need God’, came about during a psychotic episode on the beach at Margate in which Emin scrawled the words on the sea wall as a cathartic gesture of renouncement. There are tales of gleeful abandon and abject poverty from when Emin and Sarah Lucas operated The Shop on Bethnal Green Road, which ended in flames and probably a few tears. And there is the infamous appearance on Channel 4, with a wonderfully stoical Matthew Collings, where Emin turned up drunk and spouted abusive nonsense. In short, Emin is surrounded by myths and legends, which the ever-bloodthirsty media wilfully perpetuates.

The myth of a downtrodden, sexually loose, abused, hysterical woman – Mad Tracey from Margate – is, at its foundation, true. Although what is less true is the claim – promoted recently by Brian Sewell – that this makes for bad art. Emin pours her life into her art, making each piece a snatch of autobiography and transfiguring a lost past into a living present. The negative response to this mythological way of making art is to say that the works lack aesthetic merit because they are too heavily emotional, as if thrown together in a fit with no consideration for artistic value. The Hayward show finally demonstrates several reasons to reject this brash assessment of one of our greatest living artists.

The most spectacular work in the exhibition is Knowing My Enemy, a partially-collapsed wooden pier with a ramshackle beach hut at the end, which towers high above the ground into the gallery’s double-height ceiling. Emin has long been fascinated by the juxtaposition of grim sadness and holiday fever that beach huts represent. She likes the reminiscences of her childhood home by the sea and the way that wood ages, gathering into its pores an entire history while exemplifying both solidity and malleability.

This is a sublime example of Emin’s sensitivity to the fact that the meaning of art is a product of much more than mere words or pictorial representation. Emin understands that there is meaning in materials themselves, in the physical qualities of the things that constitute the artwork. In the case of the beach hut here, the wood, peeling paint, mottled glass, faded curtains speak of neglect, lost hope and vulnerability to the elements at the same time as embodying in the very core of its being a secret history imparted by the passing of time.

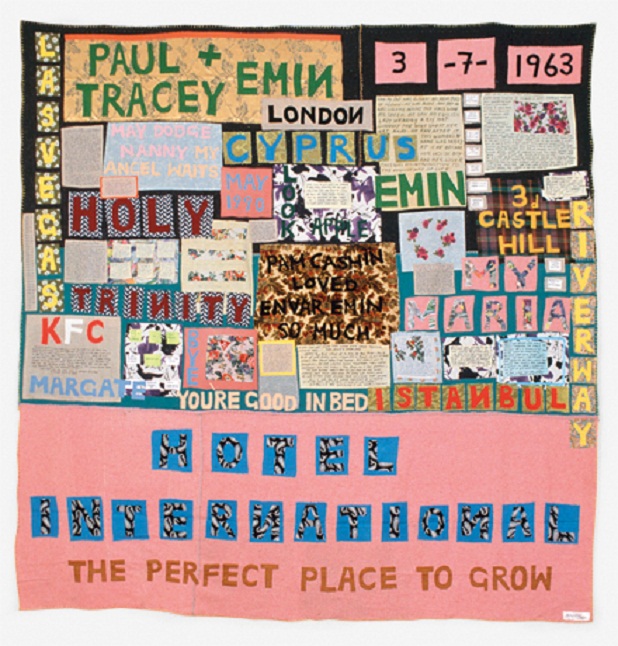

This means of expression is evident in much of Emin’s work, such as the delicate embroideries and famous quilts, where the texture of the fabric and the precision of the sewing express innocent joy and deliberation in the act of creation. Hotel International is a quilt that tells Emin’s life story in response to a request for a copy of her CV for a tour of America.

Tracey Emin, Hotel International, 1993, © Tracey Emin

The quilts are composed of swatches of fabric that are culled from her clothes, curtains and furniture, so the materials – as well as the words and images – tell her life story. It is also interesting that the refined craft of needlework is used to deal with themes of sexuality that are often brazenly vulgar, which acts as a brutal contrast between material and subject.

A central feature of Emin’s work is the use of words: the quilts particularly carry some amusing messages, such as ‘I want an international lover that loves me more than the world’ and ‘Everything you steel will turn to ash’. The use of language, with spelling mistakes and all, does not replace or override the visual art, but complements it by filling in the gaps. Perhaps it seems crude or clumsy for visual art to fill in the gaps, but for Emin it is essential to ensuring that her work tells the whole story.

This is a rare case of art being unashamedly about an individual’s life, which does not attempt to dress self-expression in art-theoretical pretensions. Whether they are rendered in fabric, paint, ink or neon, the words are funny and moving in equal measure; they allow Emin to say what she means and mean what she says, leaving no room for ambiguity.

Sure, sometimes ambiguity is inspiring and clever but, Emin realises, it is neither of these things when you are making serious art that is born solely of your serious life experiences. In short, Emin is all about autobiography and the words help her to be that, which makes her stand almost alone among her contemporaries who are fashionably obsessed with death or politics or whatever else art can latch on to in order to avoid being about the artist.

The best of her self-reflection can be found in two noteworthy works. The film Why I Never became a Dancer, in which Emin dances her revenge on the boys who shouted ‘slut’ as she disco-danced is touching, funny and gloriously ablaze with images of Emin’s childhood home of Margate. In Menphis, a full-scale recreation of a show at Carl Freedman Gallery, which takes as its starting-point the fact that Memphis – the ancient capital of Egypt – has fallen from grace as the cradle of civilisation to being a municipal rubbish dump, Emin uses assorted memorabilia to explore the way her art is the rubbish dump of her life.

The one thing you cannot accuse Emin of is obscurity. This exhibition typifies the very thing that has, for the last two decades, divided Emin’s supporters and detractors: the raw emotion, brutal honesty and unashamed method of representing it in everyday detritus. For some people, it’s just too much, amounting to little more than irritating emotional exhibitionism. It is indeed sensible to admit that, in the three hours it takes to see the whole show, sometimes you feel overwhelmed, even exhausted, by the high-octane emotional journey that the works narrate.

Nonetheless, the subject, and indeed the meaning, of Emin’s work is never a mystery. She is completely transparent, unlike many of her contemporaries, which is often thought to be a sign that she lacks depth and intelligence as an artist. This popular impression is, however, unfair, since the emotions and ideas in her work run very deep, to the very core of her being. Emin simply trades emotional depth for artistic depth, which means the works sometimes lack aesthetic fascination but always have a clear intellectual purpose, which is more than can be said for much of Hirst’s work.

In the end, it is only out of love – profound love of life and art – that Emin is able to sustain her momentum, and this exhibition has the irrepressible momentum of a life lived on the edge of impossible madness. A whole life unfolds here and sometimes it is ugly – full of despair and obscenity – but it is also replete with tenderness and affection, reflected in the care taken to make the embroideries and the delicate splashes of watercolour that comprise the small paintings.

The great Emin mythology is present at every turn because it is the very foundation of her work, although it is not as outrageous as the hype would have you believe. These works are sincere without being sentimental, shocking without being frightening, and infused with the wisdom of a woman who refuses to let go of the past. Rather than sentimental or even just plain vulgar, these works show that Emin understands the value of stark honesty; she is brutal with herself and her audience, which gives the work a great vivacity that guides you through the exhibition as if in a dream.

‘TRACEY EMIN: LOVE IS WHAT YOU WANT’ at the Hayward Gallery

will end on Monday 29 August 2011, for bookings, click here.

Daniel Barnes is a philosopher and art critic based in London, UK.

2 Comments

James Levy

Bibliography | Learning log for Textiles 1: Exploring ideas

[…] The myth of mad Tracey. In: Ceasefire Magazine. 20 August 2011. [online]. Available from: https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/radical-aesthetics-4/ [Accessed 22 May […]

‘The harrowing yet majestic experience that is Tracy Emin’! what nonsense is this Mr Barnes! as a ‘philosopher & art critic’ you of all people should know better, than to wallow in the cliched verbal dihorea, that characterises your whole article. Beautifuly written, articulate indeed, but nonsense and utter banality all the same.

The art world has like most other aspects of life been turned into a marketing strategy! indeed it could be said that life itself has been turned into a marketing strategy, where everything is a brand and people themselves have been turned into commodities!

One could easily see the art world as a nile hippo sinking further and further into the mud, due to the enormous weight of all the birds and ‘parrasites’ living on it’s back, all desperately trying to keep the poor sinking hopeless beast allive in order to survive themselves.

The psuedo intelectual candy floss of dis-information you peddle Mr Barnes, no doubt keeeps you on the guest list and pays the rent, however, it also places you centre stage as part of the problem rather than the solution!

The ‘Tortured Artist Syndrome’ which you in effect claim for Miss Emin, is such banality, and you surely must know this. Miss Emin’s main talent is for getting away with it, and in this sense, she is simply a product of her time, loud, shrill, vulgar, flashy, tasteless and drunken! This though does not transform either her or indeed her ‘art’ into Art.There is no beauty, no grace, no aesthetic value, nothing that is touching, moving or in any sense uplifting, the only thing that moves when looking at her work is ones bowels. Unlike say Francis Bacon, a genuinly ‘tortured soul, who’s work was often harrowing, but always beautiful, moving and uplifting.

Miss Emin is not an artist at all, she is in fact in the entertainments industry, one could argue of course that this is what art has become, simply a branch of the entertainments industry, and you would be right, this is what art has become, and why it has been so devalued.

One can find originality and beauty, in art in Japan, certainly Korea and most certainly in China, and one must say often in Germany, elsewhere however we see the aethetic devastation wrought by the likes of Miss Emin And Mr Hurst.

They have though been extremely succesful and become very wealthy indeed, and this today of course is what counts, and impresses. It is though a triumph of marketing and branding over genuine talent and ideas and again, like the music and fashion industry, is a product of our time. The grim reaper who effectively launched and supported all this, was of course Herr Saatchi, a marketing man posssed of power influence and most importantly money, which tends to shed light on why art has been so extrordinarily devalued. It must also be said, that most of todays ‘art buyers’ are ;people of great wealth but utterly devoid of taste or artistic sensibily.

The sad thing is, that there is some real genuine talent out there, that has been marginalised by the over marketed money making branded nonsense, a few also became succesful, Grayson Perry for example, a true craftesman who produces work that is both beautiful and original.

So, as the hippo that is art sinks into the mud, we can only hope that there are a new breed of ‘hip young gunslingers’ waiting in the wings, with the passion, originality and sensibility to wish to make the world beautiful, rather than ugly, and none of them will be called Tracy