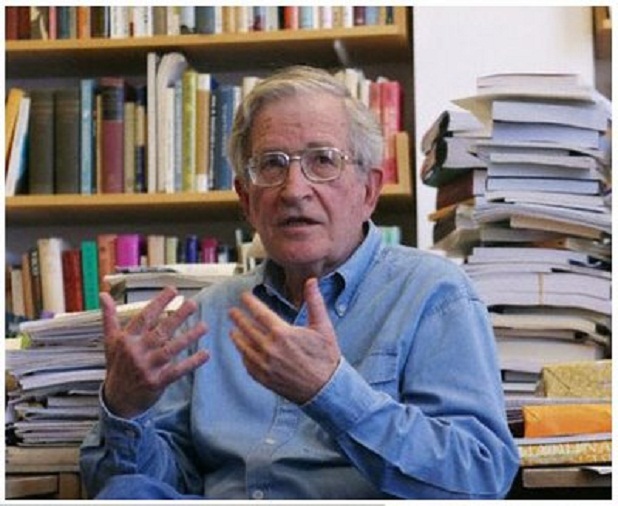

A Note on The Propaganda Model: Chomsky-Herman vs Herman-Chomsky Media

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Saturday, October 8, 2011 9:00 - 2 Comments

By Milan Rai

Many people are familiar with Noam Chomsky’s critique of the mainstream media, the “Propaganda Model” of the media. Very often, the term “manufacturing consent” is used as a shorthand for the model. As many people know, the book Manufacturing Consent has the authors listed as “Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky”, in that order, because the book was primarily written by the economist Edward Herman. (As well as contributing to Manufacturing Consent, Chomsky was writing a parallel book, Necessary Illusions, on the same theme, at the same time).

I suggested in Chomsky’s Politics in 1995 that there were differences between the Herman-Chomsky approach to the Propaganda Model in Manufacturing Consent, and what one could call the Chomsky-Herman approach in other works.

When people refer to the Propaganda Model, they often point to the “five filters” approach set out in Manufacturing Consent. These filters are the mutually-reinforcing factors that lead to a media system largely free from state control nevertheless producing highly-uniform news and opinion similar in crucial ways to that produced by a state propaganda system.

The first filter is the “size, ownership and profit orientation of the mass media”. Edward Herman gives basic financial data on, for example, the 24 largest media giants (or their controlling parent companies), and spells out the affiliations of outside directors in 10 large media companies (or their parents).

The second filter is “the advertising licence to do business”. In the case of commercial radio and television, it is transparently the case that all the funding for these media operations comes from other corporations, through advertising. In the case of newspapers, this is less apparent.

In a column on 26 September 2011, the Guardian’s Readers’ Editor, Chris Elliott, pointed out that historically 60% of a newspapers’ revenue came from advertising, but that, during the price war in the 1990s, advertising revenue crept up to 70% of the average newspapers’ income. The Observer is now owned by the Guardian. One sign in the early 1990s that the Observer was not financially viable was that advertising revenue had dropped to only 50% of total income.

Chomsky and Herman point out to us that newspapers appear to be selling news and opinion to us, their readers, but actually the main business of newspapers is to sell the attention of readers (preferably richer readers, who are better prospects for advertisers) to corporations. Just as Google appears to be a search engine, providing a free service to us, the browsing public, but actually it is a billion-dollar advertising agency, selling the attention of searchers to advertisers.

The third Propaganda Model filter is “sourcing”: “The media need a steady, reliable flow of the raw material of news…. Economics dictates that they concentrate their resources where significant news often occurs, where important rumours and leaks abound, and where regular press conferences are held”. Government and corporate headquarters are credible and recognisable sources of such raw material.

The fourth filter is “flak” – negative feedback from forces outside the media. Clearly, the more powerful and wealthy the source of the feedback, the more impact it will have. The fifth filter was originally described as “anti-communism”. It is an ideological filter, demonising enemies and reinforcing patriotic self-adulation in some way.

There is a strong emphasis in all this on the structural, a stress on corporate power and mergers and other forms of economic concentration. An industry-level analysis.

I think we generally see another emphasis in Chomsky’s work, in what could be called the Chomsky-Herman approach. While all of these factors are parts of Chomsky’s analysis of the media, the emphasis, I think, is rather on the individual surrender of each intellectual to the dominant ideology.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to use the five filters to actually analyse media coverage and to counter propaganda. Of greater operational value are the tests that Chomsky and Herman have set out for validating or invalidating the Propaganda Model and the concept of “feigned dissent”.

The three basic tests are: using paired examples, documenting the “range of permitted opinion” on a topic (also known as the “spectrum of thinkable thought”), and the most robust test of all, examining a case held up as an example of the freedom of the press, of the anti-Establishment nature of the media, to see if it actually reveals media servility rather than media independence.

Typically, according to Chomsky, those who pose as anti-Establishment voices in the mainstream media, who take anti-war or apparently radical positions, actually help to reinforce government propaganda. There are exceptions of course. In Britain, one immediately thinks of Robert Fisk, George Monbiot and John Pilger as independent journalists who manage to operate with integrity within the mainstream.

In relation to the Vietnam War, Chomsky pointed out that mainstream “doves” such as Anthony Lewis and Stanley Karnow believed the Vietnam War began with “blundering efforts to do good”, became a “noble” but “failed crusade”. Kennedy liberal Arthur Schlesinger Jr called for the war to be ended on cost grounds, opposing noted “hawk” Joseph Alsop, who believed the war could be won, but adding “we all pray” that Alsop is proved correct, in which case “we may all be saluting the wisdom and statesmanship of the American government”.

In other words, Lewis, Karnow and Schlesinger all agreed that the US invasion of Vietnam (they would never have used such a phrase) was benevolent in motivation, and morally and legally justified, though unwise. They all accepted the fundamental principle that the United States had the right to re-structure other societies by force.

By posing as opponents of the war while tacitly accepting this principle, Schlesinger and others helped to reinforce the acceptability of US imperialism. Washington’s divine right to use violence is not only acceptable, it does not even register as something that is debatable, it is a presupposition of the debate.

The debate is over when the cost-benefit analysis weighs against the use of violence. This is a prime example of what Chomsky calls “feigned dissent”. He warns that:

“The more vigorous the debate, the better the system of propaganda is served, since the tacit unspoken assumptions are more forcefully implanted. An independent mind must seek to separate itself from official doctrine –and from the criticism advanced by its alleged opponent. Not just from the assertions of the propaganda system, but from its tacit presuppositions as well, as expressed by critic and defender. This is a far more difficult task. Any expert in indoctrination will confirm, no doubt, that it is far more effective to constrain all possible thought within a framework of tacit assumptions than to try to impose a particular explicit belief with a bludgeon. It may be that some of the most spectacular achievements of the American propaganda system, where all of this has been elevated to a high art, are attributable to the method of feigned dissent, practiced by the responsible intelligentsia.”

This is, I think, the centrepiece of the Chomsky-Herman approach to the Propaganda Model, as opposed to the industry-level analysis that opens the Herman-Chomsky presentation in Manufacturing Consent.

2 Comments

John Brown's Public Diplomacy Press and Blog Review, Version 2.0

Excellent piece. ‘Feigned dissent’ is a really important concept, I think – it’s what makes ‘dissent’ in the Guardian, for example, so hard to stomach. Of course, this is precisely what we’ve seen with recent debates, e.g. Libya: whether ‘we’ have a right to bomb another country isn’t questioned, only if it’s working or not. A fundamental debate is turned into a utilitarian one (everyone agrees on aims – i.e., the wellbeing of western empires – it’s means that you’re allowed to disagree about).

[…] North Korea – Kim Andrew Elliott reporting on International Broadcasting Image from article Media A Note on The Propaganda Model: Chomsky-Herman vs Herman-Chomsky – Hicham Yezza, ceasefiremagazine.co.u: In a new essay, Milan Rai examines the subtle but key […]