Beautiful Transgressions Popular education as a living project

Beautiful Transgressions, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Tuesday, July 5, 2011 7:56 - 0 Comments

Scene from Tierra en Guerra, Universidad Nacional Colombia, Bogotá. 28 Agosto 2009

By Sara Motta

As Inga Scathach argues in her recent piece, ‘Popular Education as a Doomed Project?’[1] in Shift Magazine, popular education is a buzzword in many activist circles. As she warns however it risks becoming conflated with a set of methods which block creativity rather than enabling it. It also risks being severed from its political, philosophical and ethical underpinnings and potential.

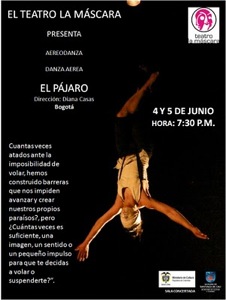

Here I explore the work of La Máscara Theatre company, the only feminist theatre group in Colombia, which works with theatre of the oppressed popular education pedagogies and methodologies, as a way of contributing to dialogues about the potential uses of popular education in the building of movements of resistance and alternatives to neoliberal capitalism in the UK (and beyond).

Isabella and Elizabeth [2], two displaced AfroColombian women, are participants in Aves de Paraíso (Birds of Paradise) community theatre groups facilitated by La Máscara Theatre. Displaced in 2001 from Nariño and Chocó states on the Pacific coast of Colombia they left the violence of state sponsored paramilitary groups and guerrilla groups to arrive into the violence of urban poverty and exclusion.

Elizabeth is a grandmother, tall, proud with lines of sorrow around her eyes. Isabella is a single mother of five children, with a deep voice and laugh and a well of sadness in her eyes. Ageless and yet with the weight of much suffering on their shoulders they have participated in the theatre group for 4 years. It is, as Isabella told me, a space of peace, of escape, of warmth and humanity. It is a place of laughter and creativity where for a moment the realities of physical, cultural, economic and political violence are overcome.

Cali, the second city of Colombia, has been a harsh place for them: a place of much racism and discrimination, of individualism and consumerism where the displaced are viewed as thieves, delinquents, uneducated, where their children suffered verbal and physical abuse at school, where they suffer the humiliation of poverty and the desperation of hunger.

Isabella recounted an experience in the first years that she arrived in which her children and she hadn’t eaten for two days. She walked for miles to get to a health centre where they handed out fortnightly rations of food. She was at the point of giving up. The doctor met her. She wept pleading for at least a handful of rice to take to her children. But the doctor said no, there is nothing. Isabella knew there was food, and remembers this as one of those moments in life that marks you for the intensity of privilege, power and cruelty exercised.

She walked back to her shack weeping. Arriving to see her youngest child on the floor not moving and her other children sitting still, their eyes lifeless and heads down. She let out a scream. No more.

Her neighbours came; they bought a tuna fish, some rice, and a plantain. Yet her scream became transformed into a song, a song that speaks of her values and dignity and criticizes the values of pride, possession and power over others that she has experienced in Cali, one of the most Americanized and commodified cities in Colombia.

As both explained in their tierra (land) no one went hungry. There was always food as they lived in the countryside where there was abundance. Neighbours shared and supported each other. Now the region where Elizabeth is from has become taken over by multinationals supported by the Colombian Government who grow Egyptian Palms for export which destroy the surrounding land further undermining further campesino (peasant) ways of life.

To be violently displaced in this way from your land, way of life and community and arrive to more violence and displacement is a form of long term trauma. The violence in their lives is multi-dimensional; the way that the power of the US, the Colombian state and neoliberal capitalism has scarred and traumatized their lives cannot be understood or transformed from the outside or by a model developed in another place and another context. Such violence is intensely placed, subjective, affective, intellectual and psychological.

It is this multidimensionality of power, its affects and how one transforms these conditions into liberation and social justice that is one of the major problematics of La Máscara theatre which since 1972 has developed contestatory theatre and theatre of the oppressed based on collective creation dedicated to the thematics of gender and women.

The theatre of the oppressed, a manifestation of popular education, seeks to facilitate processes of collective understanding, representation and transformation through the development of theatre. Its objective is self-liberation from oppression, facilitating the self-liberation of people from the passive state of spectator to actors that self determine the theatre but also their everyday lives. As theatre is multidimensional – affective, cultural, psychological, embodied, physical and intellectual – it has the potential to transform the multidimensional nature of oppression.

The theatre of the oppressed, a manifestation of popular education, seeks to facilitate processes of collective understanding, representation and transformation through the development of theatre. Its objective is self-liberation from oppression, facilitating the self-liberation of people from the passive state of spectator to actors that self determine the theatre but also their everyday lives. As theatre is multidimensional – affective, cultural, psychological, embodied, physical and intellectual – it has the potential to transform the multidimensional nature of oppression.

For La Máscara the key elements of their work are that it is dialogical and integral in the types of collective and individual experiences developed. They facilitate free play which accepts and values people’s life experience, diversity and expressions and create experimental space in which communities have the time and space to reflect upon their realities and experiment with their transformation. They also encourage rebellious thought, promoting ideas, perspective and actions that are non-conventional and which generate social and political action.

They use the power of laughter in a way that relativises the power of order and control through the counter power of uncontrollable laughter. They oppose desperation and bitterness with the power of liberatory laughter. As Elizabeth expressed, ‘It would be so easy to be full of bitterness, to become cold hearted. Here we prevent this and keep it at bay. This doesn’t mean we don’t continue to suffer but it does mean that it doesn’t destroy us.’

Finally they are dedicated to public work, making visible to the public the self liberation and determination of otherwise excluded and demonized communities. As Isabella explained, ‘We have shown our work in Cali. It creates a bridge between displaced communities and Caleños from which we can begin to imagine collective projects of political and social change. Our work really needs to be presented in every barrio (community)’.

Theatre of the Oppressed brings the creative, affective and intellectual capacities of communities and individuals to the centre of the praxis of social transformation. As Pilar Restrepo Mejia participant in La Máscara explains, ‘Amongst the arts, theatre possesses the privilege of being a live art, which allows us to see the complexity of social relations and interpret reality in an inventive way, which develops an experience of reflection. Theatre becomes an extraordinary instrument for people and community development.’

In particular La Máscara aims to make visible women’s struggles, suffering, and the violence they confront and through this process make manifest the dignity, strength, knowledge and creativity of women who are otherwise represented as either merely victims or dangerous delinquents.

Working with women like Isabella and Elizabeth, they support the development of theatre groups in marginalized communities. In the case of the group in which Isabella and Elizabeth participate La Máscara had worked with la Hermana (sister) Alba Stella Barreto founder and director of Fundación Paz y Bien in Comuna 14, Aguablancas shanty town.

Working with women like Isabella and Elizabeth, they support the development of theatre groups in marginalized communities. In the case of the group in which Isabella and Elizabeth participate La Máscara had worked with la Hermana (sister) Alba Stella Barreto founder and director of Fundación Paz y Bien in Comuna 14, Aguablancas shanty town.

Their objective was to building a theatre group with the participants in the community. The group in Comuna 14 – one of 8 groups formed- was comprised of women and children, all displaced AfroColombians from the Pacific coast regions of Cauca, Chocó and Nariño. They built on the rich traditions of song, dance, storytelling and poetry of their communities.

Elizabeth is a poet and Isabella a story teller. Yet the traumas they have faced meant that for both their everyday experiences of hunger, homelessness and humiliation left little space for reading, writing or story telling. Their participation in the theatre group helped to develop these skills and talents challenging them into thematics of displacement chosen and developed by the participants.

Their last work Tierra en Guerra (Land at War) was a shout of dignity in the face of discrimination and demonization. It captured their lives as they had been in their tierra, land; the richness, knowledge and histories of their communities, as well the experiences and causes of their displacement.

Using body, mind and spirit it was a means of representing their reality and humanity to each other and the world, of turning upside down the stereotypes and representations of Caleña (Colombian) media, politics and culture.

The process of collective construction itself was a process of self-determination and discovery and strengthening of voice. It transforms one’s (both as an individual and as a community) relationship with pain enabling pain to become a basis of courage and self-actualisation.

In Elizabeth’s words she describes ‘when I arrived in Cali I couldn’t express myself. I was panicked and shaking all the time. In the group I have built the confidence in, myself and my abilities’. Or as Isabella explained ‘they say we are ignorant and we can’t talk Spanish properly. I knew what I wanted to say but my tongue wouldn’t work. My self esteem had been destroyed. The projects, Lucy and others with their love and warmth and sincerity have helped me feel I have knowledge, understanding and rights. I still shake, I still suffer but there are lights of hope, places of breathing’.

Facilitators are trained in a number of elements to enable them to bring to fruition the development of plays and help build and sustain the group. These are corporal expression, vocal and instrumental techniques, introduction to theatre conventions, stimulation of dramatic creation of narratives, non-verbal language, acting and concepts of improvisation and dramatic organization.

An example of an exercise used to develop dramatic creation of narratives is through written texts. As it is possible to develop a work of theatre through a poem, a song or a written text by one of more participants the exercise begins by asking the participants to write a text o poem in relation to a chosen theme. In groups improvisations are developed to explore how one might use such a text to develop the theatre piece. Oral elements are also introduced in the improvisation such as oral stories, dreams, anecdotes, life stories.

Facilitators need to be able to recognize that which is most needed in the group and therefore how to orientate the work and process of collective construction. The facilitator of Aves de Paraíso used yoga as a way of helping the affective psychological healing from the long term, and ongoing traumas experienced by participants. Thus all meetings, once a week for 4 hours begins with yoga work.

She also encouraged participants to build on cultural traditions of story telling, enabling a re-telling of stories of trauma as a means to transform these stories creatively with a pedagogy that facilitates a distancing from the most painful experiences.

Collective processes of story telling and improvisation create links of solidarity and enable an overcoming of the monologue of isolation into dialogues of understanding, voice and pleasure. As Pilar continues ‘Telling stories is a way of reconstructing reality, and sometimes, it also enables the healing of deep wounds.’

Aves de Paraíso’s next work moves away from a focus on displacement and violence, which as Isabella and Elizabeth explained they feel they have exhausted, are exhausted by. Instead it develops a utopia of how the world would be if all women joined together to overcome violence, to encourage men to move way from violence against each other, over money, power, resources and pride. It is an act of envisaging a different world. Whilst a representation, it fuels their everyday struggles against violence and attempts to construct moments of paradise on earth.

Theatre of the oppressed, as a form of popular education, visbilises and actualises multiple knoweldges – the affectual, the experiential, the cultural, the intellectual and the spiritual. It transforms the way that knowledge is created away from its representation in the figure of the abstracted and disembodied intellectual to a process of embodied (in the community and in the self) collective construction that is inseparable from action.

By conceptualising the multidimensional nature of power it expands and challenges traditional forms of politics which claim that politics resides in the public sphere, is organised by great ( often male) leaders and is comprised of heroic events and particular actions. Fundamentally it is premised on an ethical commitment to recognition of the other as part of a recognition and realisation of the self.

Such processes do not seek to name or fit their praxis into any ideological box or political model. Rather they are constantly open to development, creativity and uncertainty. The knowledges and practices that result are living, relevant and transformatory.

This one example from the multiplicity of experiences, histories and expressions of popular education suggests that it would be unwise at this political conjuncture to close off our political imaginary, through a dismissal of its relevance, to our political context.

Rather it is urgent to cultivate an ethic of openness, dialogue, experimentation and exploration. Only in this way can we hope to break out of the straightjackets of politics as normal.

Sara Motta is a mother, radical educator and writer.

[1]A longer version of this article with a slightly different focus, can be round at – http://nottinghamcriticalpedagogy.wordpress.com/2010/12/26/aves-de-paraiso-theatre-of-the-oppressed-in-cali-colombia/

[2] Names have been changed for reasons of security and safety

Leave a Reply