The Anti Imperialist Language as Weapon

New in Ceasefire, The Anti-Imperialist - Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2011 0:05 - 0 Comments

By Adam Elliott-Cooper

By Adam Elliott-Cooper

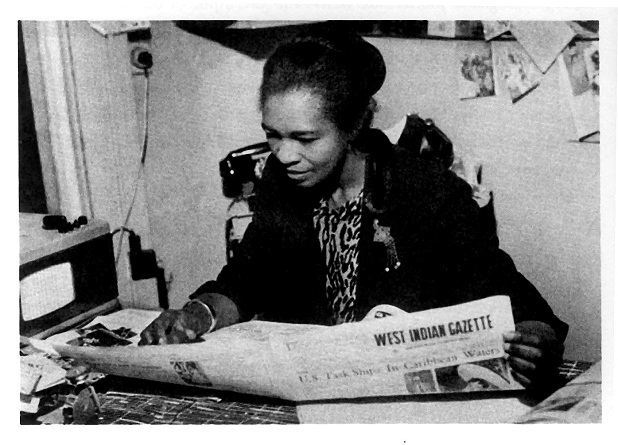

The professionalization of race equality is a phenomenon that has been written about extensively. The social movements fighting racism in the 1960s through to the 1980s were transposed to more manageable institutions by the Thatcher government. The CRE (Commission for Racial Equality), which is now the EHRC (Equality and Human Rights Commission), numerous government posts, particularly within the Home Office, and a host of think tanks and charities attempted to co-opt the intellectual minds involved in these movements, offering progressive research, a comfortable salary and a prestigious title.

For many people, these types of organisations are inviting; for others, they feel like a poor set of options. There has been a long struggle between the advocates of mainstream dominance and the more critical and radical voices who have entered these institutions and attempted to re-link them to the grassroots struggles for racial justice. The mainstream has worked hard to water down and de-politicise race equality, and one of the tools used to do this is language.

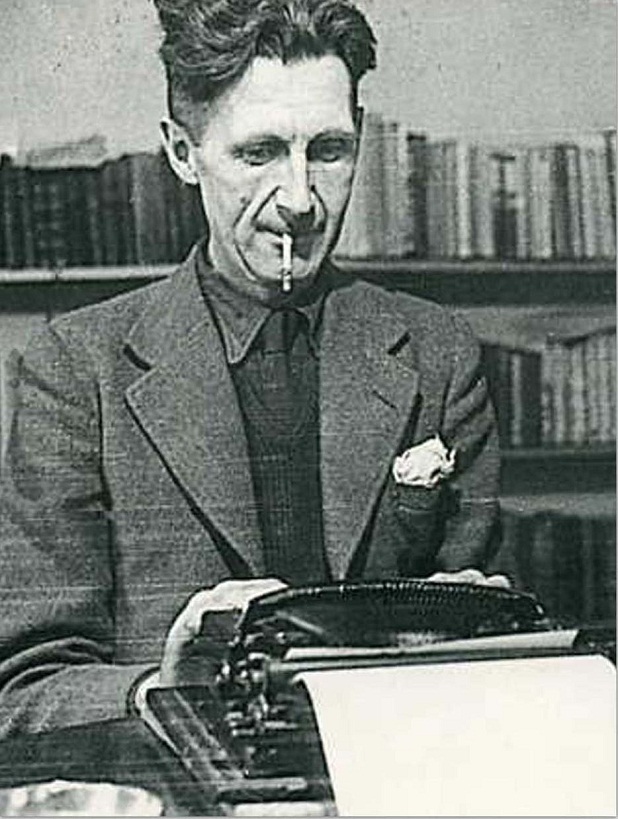

Few have observed the way in which language is used to water down radical critique or depoliticise the struggle for justice more eloquently than George Orwell. In his book 1984, he refers readers to the appendix, in which Newspeak, the government-imposed language of the dystopic Ingsoc, is deconstructed. For the totalitarian government in 1984 “Newspeak was not only to provide a medium of expression for the world-view and mental habits proper to the devotees of Ingsoc, but to make all other modes of thought impossible”. This sounds like a far-fetched idea belonging only in science fiction; however, Orwell goes on to explain how this can be done:

“The name of every organization, or body of people, or doctrine, or country, or institution, or public building, was invariably cut down into the familiar shape; that is, a single easily pronounced word with the smallest number of syllables that would preserve the original derivation.… It was perceived that in thus abbreviating a name one narrowed and subtly altered its meaning, by cutting out most of the associations that would otherwise cling to it. The words Communist International, for instance, call up a composite picture of universal human brotherhood, red flags, barricades, Karl Marx, and the Paris Commune. The word Comintern, on the other hand, suggests merely a tightly-knit organization and a well-defined body of doctrine. It refers to something almost as easily recognised, and as limited in purpose, as a chair or a table. Comintern is a word that can be uttered almost without taking thought, whereas Communist International is a phrase over which one is obliged to linger at least momentarily.”

“The name of every organization, or body of people, or doctrine, or country, or institution, or public building, was invariably cut down into the familiar shape; that is, a single easily pronounced word with the smallest number of syllables that would preserve the original derivation.… It was perceived that in thus abbreviating a name one narrowed and subtly altered its meaning, by cutting out most of the associations that would otherwise cling to it. The words Communist International, for instance, call up a composite picture of universal human brotherhood, red flags, barricades, Karl Marx, and the Paris Commune. The word Comintern, on the other hand, suggests merely a tightly-knit organization and a well-defined body of doctrine. It refers to something almost as easily recognised, and as limited in purpose, as a chair or a table. Comintern is a word that can be uttered almost without taking thought, whereas Communist International is a phrase over which one is obliged to linger at least momentarily.”

Whether or not we agree with Orwell’s description of ‘Communist International’ is irrelevant. For many people in the powerful anti-capitalist movements of the time, the words ‘Communist International’ contained huge significance and symbolism. This can be transposed to words like African Caribbean or Black in the field of race equality today. For me, Black, in the British context, is a political term that was reclaimed in the 1950s to mean any person who suffers racial oppression, be they of African, American, Asian or Australasian descent. Being politically Black engenders ideas of Malcom X, the Black Panthers, the Brixton Uprisings, roots reggae and the Notting Hill Carnival. When someone says ‘African Caribbean’, it conjures up an image of people who are from the Caribbean but who have their roots in Africa. It immediately links to imperialism, slavery, the destruction of indigenous Caribbean peoples and the former British Empire which brought Africans them to Europe.

Among the myriad acronyms and abbreviations used in government and policy, BME now dominates the race equality sector. BME stands for Black and Minority Ethnic. The first thing this abbreviation does is separate Black people (in this case African and African-Caribbean people) from other ‘minority ethnic’ peoples, such as those of Asian or Latin American descent. The second thing it does is make the word ‘minority’ central; however, this is a disempowering word and is often avoided for this reason. If not using the word Black to describe non-Europeans, then the term ‘Global Majority’ is a far more accurate and empowering designation.

Finally, of course, the ‘BME’ tag reduces the identities of victims of white supremacy to a single, three-letter abbreviation which, as a relatively new word, is divorced from the long history of oppression and resistance to racial subjugation. It is a prime example of what a friend of mine calls a TLA – a three-letter acronym.

Finally, of course, the ‘BME’ tag reduces the identities of victims of white supremacy to a single, three-letter abbreviation which, as a relatively new word, is divorced from the long history of oppression and resistance to racial subjugation. It is a prime example of what a friend of mine calls a TLA – a three-letter acronym.

Or, as Orwell put it, “words of two or three syllables, with the stress distributed equally between the first syllable and the last. The use of them encouraged a gabbling style of speech, at once staccato and monotonous. And this was exactly what was aimed at. The intention was to make speech, and especially speech on any subject not ideologically neutral, as nearly as possible independent of consciousness”.

The ability to articulate our experiences, feelings and demands depends on us having the necessary language to formulate and communicate them, both to ourselves and to each other. Without this skill, it is near-impossible to think, organise and act. It is for this reason that those in power attempt to subtly water down the language of empowerment, and it is this subtlety which we must be aware and suspicious of. It is only through articulating our own politics that we have the agency to deliver accurate critiques and build our own alternatives.

Adam Elliott-Cooper, a writer and activist, is Ceasefire Associate editor. His column on race politics appears every other Sunday.

Leave a Reply