Yanis Varoufakis: “Never before have we had so much money, yet so little investment in what humanity needs” Interview

Editor's Desk, Interviews, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Monday, July 29, 2019 8:27 - 5 Comments

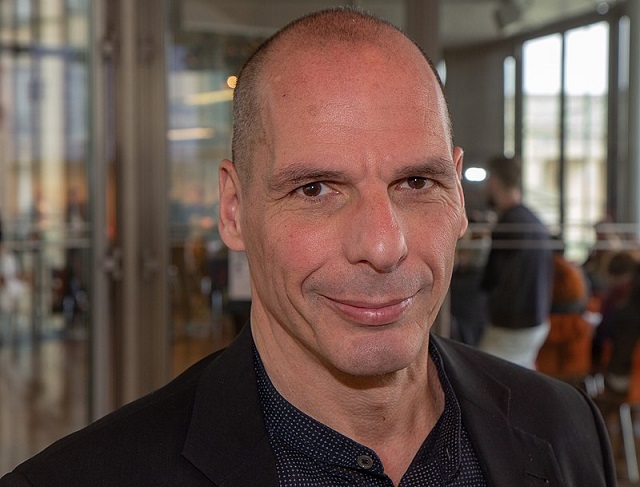

Yanis Varoufakis (Credit: Olaf Kosinsky/Creative Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0 de)

Laura Siegler: With the economic rift seemingly still expanding between Southern Europe, on the one hand, and the ‘core’ European countries (Germany, Benelux, France, Scandinavia) on the other, what is the scope for a common environmental agenda of the European left?

Yanis Varoufakis: This question is not just global but also within Europe, because the fragmentation of oligarchy — of capitalism and financialised capitalism — is detrimental to any attack against the climate extinction we are facing. We have a remarkable disconnect, an imbalance, between the amount of liquidity, of money which is available, and the amount of investments — the things the humanity needs. Never before have we had so little investment in what humanity needs, in relation, as a percentage, to the available money. We have the highest amount of savings in the history of capitalism, and the lowest levels of investments, in comparison, especially in the technology of the future that will prevent the climate catastrophe.

So this is a global problem, a European problem, but also one within our countries. If you live in the UK, you have amazing disparities between investments in the south and the north, between East and West, between London and the rest. This is a disease, and it is the result of the manoeuvring which we have dealt with in the 2008 crisis, and in the build-up of financial bubbles before that. What happened when those bubbles burst in 2008 has been a policy of “socialism for the bankers and harsh austerity for anyone else” which then perpetuates itself in this manner.

So to answer your question succinctly after a very long intro, we need public institutions, the purpose of which will be — across the world, at a UK level, national level, European level, and internationally — to energise idle cash into the technologies of the future, and they will be doing this in a way that makes sense from the planet’s perspective. Because this is a planetary crisis, a UK crisis, a European crisis. So, you need two things: firstly, public institutions, and to put money to good public use; and you need a massive redistribution of wealth and not just income, of property rights also, from global North to global South.

LS: When we think about challenging inequality and climate change from a European perspective, and with the North and South divide in mind, is transnational democracy a solution? Can the national and transnational really work together in finding solutions to tackle climate change? Considering, for example, that Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic recently refused to sign the European net-zero carbon emissions target for 2050?

YV: We certainly need transnational democratic institutions. All the bad people have them: the bankers are transnational in their institutional organisations. When the banks failed, they managed to create a network of solidarity between them and the central banks. The fascists too — look at Steve Bannon — are organising transnationally and internationally. Only the progressives and ecological movements are failing to do so. So, we need transnational institutions. And since there are going to be progressive ones representing the many, not the few, as Jeremy Corbyn would say, they better be democratic. It is a huge challenge.

Diem25, the movement that I belong to, has been trying for three years to put this together in Europe. We have succeeded within the microcosm of Diem25, which is a good laboratory of transnational democratic politics. But how to scale this up is the challenge. All I can say is that unless we succeed, it is Game Over for all of us.

LS: What could be the risk in speaking in the name of a transnational people — without having constructed one yet — in the struggle for environmental protection?

YV: The juxtaposition between the national and the transnational was always a constructed one; in exactly the same way that the nation is a constructed one. Up until 150 years ago there were no nation states; we had multicultural, multinational empire states. (The UK is a multinational state as we speak. Tell a Scot they’re English and you’ve lost them as friends for ever).

So, the question is: where does the sovereignty come from? Where does the power of the people come from? The more global the problem becomes — whether this is climate change, or public debts, or banking, or protection of worker rights in the face of automation — the greater the need for an expansion of sovereignty and of people power beyond the limits of borders.

LS: How can Europe secure the net-zero carbon emission target by 2050 without shifting the burden onto developing nations, especially through the use of carbon credits?

YV: The way to do it is by not dumping anymore on the developing world. Today, what we are doing, what Europe is doing, is dumping all our rubbish; and this has been going on for decades. The key is not to produce rubbish and not to use fossil fuels. If you don’t use fossil fuels you don’t need carbon credits, you don’t need to seek out countries in Africa or Asia that will effectively lend you the right to pollute. This is what carbon credits are.

We now have the technology to move to a world of zero emission without any transfer of ‘bads’ (as opposed to goods), from Europe to the rest of the world. All we need is money, and the fantastic fact is that we have the money. Never before has Europe had so many idle savings. We have negative interest rates across Europe, even in countries that are poor, interest rates are negative. That should ring an alarm bell, that there is something fundamentally wrong, because moneyed people are prepared to pay governments for the right to lend to them. So why are we not taking this money to put it to good use? The answer is because capitalism is structured in a way that generates coordination failures.

LS: Does that mean the nationalisation of energy networks at large as well?

YV: Not necessarily, it could be socialisation. The beauty of zero-emission technologies, of renewable energy, is that it’s fundamentally decentralised in a way that traditional energy technologies never were. So now the technology is amenable to democratisation, because you can have every house, every neighbourhood owning its own battery cells and its own wind farms and its own solar panels. And they can all be simultaneously producers and consumers of energy in a smart, decentralised system that doesn’t belong to anyone except to society; even without the state intervening. So there is a great prospect of moving toward a social economy model where you have public ownership, with individual homes and communities participating both as consumers and producers.

LS: Do you have an example of a nation-state that is based on that functioning at the moment?

YV: No, not an example of a nation-state, but you can look at communities where this is happening. You have to remember that this is how capitalism emerged in Italy at the beginning of the renaissance. Some cities had cells of capitalist economies that had moved away from feudalism, and once those became viable, at some point, capitalism spread to the rest of the world. So as long as we have communities that operate along the lines of a decentralised grid of renewable energy — production and distribution — then scaling it up is just a technical issue.

LS: Diem25 just won 9 parliamentary seats at the general election in Greece. Looking back, what did you learn from your resignation from the government in 2015 and what can Diem25 do to revive the opportunity for a radical shift to the left that Syriza failed to achieve?

YV: What I learned in 2015 was that the greatest enemy of progress resides within progressive parties. We didn’t lose because of the ironclad enemy, we knew that the enemy would be ironclad, and would try to throttle us, as always when it comes to the left. We lose because we fall out with one another, because we don’t hold the line, because some go over to the other side. It happened in Britain in the 1920s when the labour party was fresh, with Ramsay Macdonald, who introduced the end of austerity as a Prime Minister in cahoots with the Tories. It happened in Greece in 2015.

It is essential that we have a movement that completely controls the government, as opposed to a government that uses a movement in order to become autonomous. The moment the government becomes autonomous of the movement, it becomes exceptionally easy for the establishment to co-opt it. That is the lesson I learned from 2015, that’s a lesson we knew already but we were blind to the fact that it was not being learnt by the rest of us in the party and in the government.

We were a campaign that to many looked hopeless but, nevertheless, because we concentrated on programmatic language, to speak on the basis of what needs to be done — no negative characterisation of opponents, no mudslinging — we stood on the foundation of proposals for all those issues that wreck people’s lives and keep them awake at night and send their children to forced immigration. And, in the end, it was appreciated, we went up in other countries a couple of times, we held debates, not simply giving speeches or conferences; we had long, hard, arduous debates and in the end that was appreciated.

So now we end up with a small number of MPs but still a significant one, 9 out of 300. Our gigantic task is to be the only credible opposition because I’m afraid that my former Syriza colleagues don’t have what it takes to oppose the new government. And the reason why I am saying this is because they signed into law all the austerity and privatisation measures that now the right will happily implement. Therefore, what will Syriza say to them? Bring back the airports, the airways, the pensions? End austerity? Mr Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the new rightist authoritarian, will turn around and say: but you brought all this in, you signed all that into law.

So the duty of Diem25’s parliamentarians is to carry the huge burden of opposing the rightist government but also the foundation of the agreement between the previous government of Syriza with the Troika, on which the most parasitic oligarchic regime is being built now by means of the new government.

LS: Does the appointment of Christine Lagarde as president of the European Central Bank signify the death of the Troika, should a new crisis arise?

YV: Firstly, I cannot possibly accept the premise on which the question is based, which is that the crisis has ended and that ‘another’ crisis may come. The crisis never ended. The crisis that began in 2008 is metamorphosing, enfolding, developing, evolving, but it has never gone away. So, it is the question of the same old crisis, taking on a new form.

Secondly, Christine Lagarde is part and parcel of the Troika. She was there from the beginning. She is not capable of moving beyond the logic of the Troika. The great question regarding her being the new head of the Central European Bank — the great problem she is facing — is that she is going to replace a man, Mario Draghi, who’s been credited with saving Europe, even though the policies that he left behind for her to use are now no longer fit for purpose. So, she is facing a gigantic challenge, because if she sticks to the policies of Mario Draghi she will fail, because these policies can no longer do the job, and if she diverts from them, she will be accused of abandoning the great man’s policies.

LS: Thank you very much Yanis.

YV: Thank you very much.

This interview was conducted on 14th July 2019 at the International Social Forum in London. The text was lightly edited for readability and concision.

5 Comments

Jason

Good post!

We’ve got a competent, industry-renowned quality assurance department comprised of five-star rated in-house editors. When your assignment expert finishes your assignment, this team takes over to check for and rectify any mistakes.

Dealing with a capstone project high school requires knowledge of how to write it correctly to satisfy the demands of your college and gain some privilege from the examination board tutors.

bioinformatics assignment help

We provide the students with the much-needed assistance to make an assignment by offering bioinformatics assignment help. Our experts are bioinformaticians who have been practicing in the field for years.

They have all the knowledge of software used in the field. Our experts will help you with bioinformatics solutions. We are not just a website that provides you with assignments. But, we are a leading website that assists students to make their assignments per the guidelines provided by the institutions. Bioinformatics assignment solution is one such service provided to students. Services get offered by people experienced in the subject matter.

We should remember that at the end of the day this guy Yanis Varoufakis is part of the establishment no matter how revolutionary they look like