Their Violence, Our Values: A History of European Responses to Political Dissent Analysis

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, March 25, 2016 16:38 - 2 Comments

By Asim Qureshi

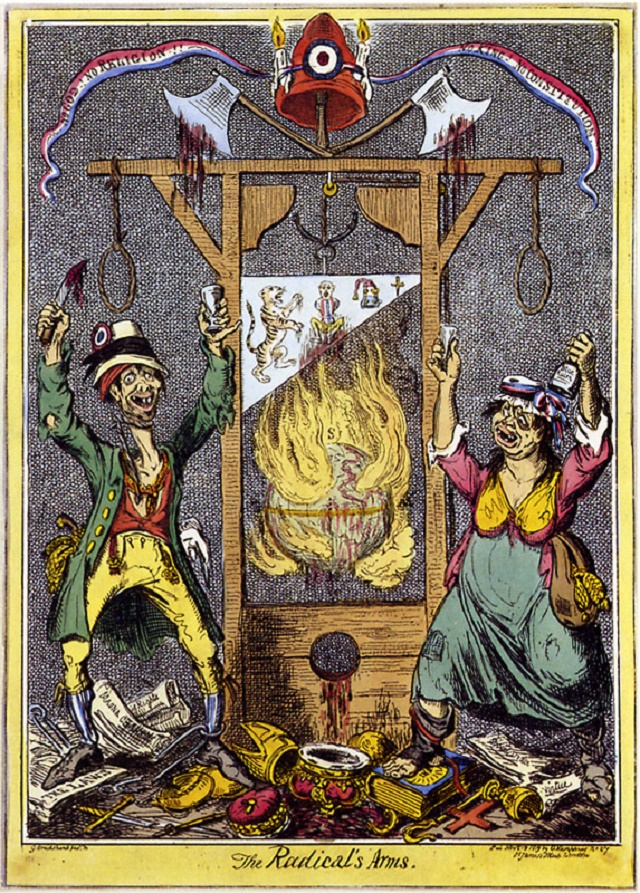

A 1819 caricature by George Cruickshank mocks the ‘Radicals’ campaigning for parliamentary reform as dangerous murderers and debauched atheists.

Terror, Ideology and Fear: A Very European Story

The latest terrorist attacks in Brussels, widely-believed to be the work of Islamic State, have reignited the debate about how Europe should deal with the threat of political violence domestically and internationally. Since the attacks of 11 September 2001, the prevailing narrative has been to place this struggle within the context of an ideological war – a war based on conflicting value systems. This notion was epitomised the morning after the Paris attacks by Jacques Reland, of the Global Policy Institute, who, commenting to the BBC, stated:

“I see it as a continuation of the war against the values of the West. I see it as an attack on French society, French way of life, French culture, on more than that, on European values, democracy and freedom.”

In a similar vein, Bruno Tertrais, of the French thinktank Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, was quick to reiterate the line that, “This is a war of ideas”, explaining how:

“…what was targeted on Friday night was, once again, about the very identity and soul of Paris, the ‘capital of abominations and perversions’, according to Islamic State. Most French people were surprised to see their uber-secular country described as the one that “carries the banner of the Cross” by Isis’s vengeful communiqué. The point here is that French policies in the Middle East are a secondary rationale for armed jihadists. President Hollande said as much in his short Saturday morning address: we are targeted for what we are.”

Such statements are not unique. Rather, these sentiments have formed as part of a consistent narrative that places such moments of brutality within a larger continuum, one that requires an ideological response to a supposed fundamental clash in values, rather than to politically-motivated violence anchored in real-world grievances.

After the Madrid bombings in 2004, the-then Spanish Prime Minister, Jose Maria Aznar, claimed:

“The problem Spain has with al-Qaeda and Islamic terrorism did not begin with the Iraq crisis. In fact, it has nothing to do with government decisions. You must go back no less than one thousand three hundred years, to the early eighth century, when a Spain recently invaded by the Moors refused to become just another piece in the Islamic world and began a long battle to recover its identity.”

This notion has been reiterated by a number of statesmen over the years. Tony Blair led the charge with his rhetoric about defeating ‘the ideology of evil’. Despite a change in government and a commitment to thinking differently about counter-terrorism policy, the Tory and Liberal Democrat coalition continued that line of thought. It has followed through to the Tory majority we have now.

The UK government’s latest counter-extremism strategy suggests that ‘extremism’ – and, in particular, ‘Islamist extremism’ – present a new threat that requires an exceptional response. Senior figures from the Conservative Cabinet have spoken about the way in which this particular struggle is one over values. The issue has become one of protecting the British or European “way of life”, with the Prime Minister David Cameron claiming:

“The fight against Islamist extremism is, I believe, one of the great struggles of our generation. In responding to this poisonous ideology, we face a choice. Do we close our eyes, put our kid gloves on and just hope that our values will somehow endure in the end?”

To what extent can we make the claim that the government’s current process and thinking is a response to the extraordinary? Could the threat of terrorism, and our response to it, be situated within a longer European historical tradition?

In this essay I argue, principally through the prism of two recent works by historian Adam Zamoyski and anthropologist Laleh Khalili, that counter-extremism policies pursued by the UK government, and its counterparts across Europe, are not extraordinary or recent developments, but belong to a long-running historical tradition.

Europe Versus The Enlightenment: A Forgotten History

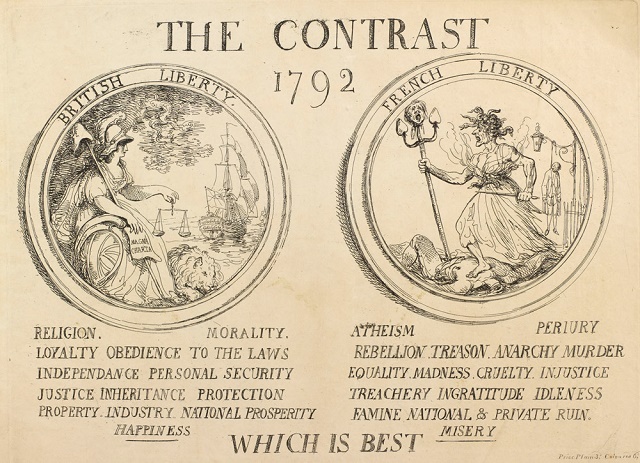

A 1792 etching by Thomas Rowlandson, published on behalf of the Association for the Preservation of Liberty and Property against Republicans and Levellers. (Source: http://www.brh.org.uk)

While Adam Zamoyski’s book, Phantom Terror: the threat of revolution and the repression of liberty (2015), does not seek to answer any of the questions posed above, he does leave the parallels for us to draw:

“The deeper I delved, the more it appeared that this panic was, to some extent, kept alive by the governments of the day. I also became aware of the degree to which the presumed need to safeguard the political and social order facilitated the introduction of new methods of control and repression. I was reminded of more recent instances where; the generation of fear in the population – of capitalists, Bolsheviks, Jews, fascists, Islamists – has proved useful to those in power, and has led to restrictions on the freedom of the individual by measures meant to protect him from the supposed threat. A desire to satisfy my curiosity about what I thought was a historic cultural phenomenon gradually took on a more serious purpose, as I realised that the subject held enormous relevance to the present.”

Zamoyski’s book details the extent to which European countries of the 18th century, including Britain, adopted repressive counter-terrorism/extremism measures out of a fear that the ideals of the enlightenment would radicalise a generation of young and impressionable minds. Zamoyski traces how, rather than focusing on the causes of disenfranchisement within their populations, the monarchies of the day blamed ideology as the root cause of ‘seditious’ thinking, much in the way that Cameron does today (“We know that terrorism is really a symptom; ideology is the root cause.”)

Enlightenment thinking and other subversive ideas were considered a threat to the status quo of power within Europe. Emperor Joseph II of Austria took the view that all such thinking should be repressed, as he

“… believed in shielding his subjects from what he saw as the false philosophy and ‘fanaticism’ of the Enlightenment. He circumscribed the educational system and in 1782 abolished the University of Graz. He strengthened an already strict censorship, which came naturally to him in view of his loathing for scribblers’. As well as covering the usual subjects such as religion and the monarchy, it was focused on promoting ‘the right way of thinking’. He was wary of sects, as he referred to almost any association, from Masonic lodges to reading clubs, in the conviction that they spread ‘errors’. Foreigners were the subject of intense suspicion, and they were watched assiduously, as were the clergy.”

Furthermore, since many of the ideas that underpinned the French Revolution were initially identified with specific groups or sects, many of which had emerged in universities, the response of European states to the emergence of such groups was to try to shut them down.

Austria was not alone in taking such measures. Similar policies were being put in place across Europe in countries such as France, Germany, Sardinia and Russia, but it was the Austrians who squarely entrenched a formal process of PREVENT-like policing within their society.

Within a few days of the accession of Emperor Francis to the Hapsburg throne, a new era of repression began, with its focus particularly on ordering the police to, “maintain a constant and thorough watch for the spread of ‘the fanatical pseudo-enlightenment’ and any other ideas that might threaten public order.”

Moreover, ideas being disseminated to school children became an early focus. An imperial resolution was passed on 10 March 1796 to establish “… a school police, whose job it was to invigilate the moral and orderly behaviour of pupils at primary and secondary schools, and to keep watch over the morals as well as the political attitudes of their teachers. Just as actors were forbidden to ad-lib, teachers were forbidden to ‘improvise’. They were to use only approved textbooks, and avoid touching on political subjects even if they took an orthodox line, since they might inadvertently give their pupils the wrong idea.”

The Europe-wide monarchical response had its detractors. A young Duc de Richelieu counselled moderation, arguing that: “It will be with this one as it has been with all those which have agitated the world. If it is left to itself it will die and vanish into the void from which it should never have emerged; if, on the contrary, it is persecuted, it will have its martyrs, and its lifespan will be prolonged far beyond its natural term.”

The British Whig government of the period did little to resist the excesses taking place in the rest of Europe, but rather followed the same route. As Zamoyski writes, Edmund Burke, staunch opponent of the French Revolution, “equated the desire for change of any sort with revolutionary purpose, warning that [if] the Dissenters … had their way Christianity would be extirpated’.” Indeed, Burke, “bracketed anyone who did not hold the same views as himself as a ‘terrorist’, and accused English journalists of being in the pay of the Paris Jacobin Club.”

In 2015, the idea that ‘extremist’ thoughts and beliefs are a real and present danger to UK society has resulted in similar experiences for Muslims. Landlords are told by security officials that their tenants are involved in ‘extremist’ activity, resulting in evictions without any evidence or cause; meeting rooms cancel events where ‘extremist’ figures are due to speak; and public figures are removed from their posts due to concern over their beliefs and ideas. All of this remarkably mirrors much of what Zamyoski describes of 1792’s Britain:

“Landowners threatened tenants with eviction if they held radical views, employers sacked workers, tradesmen and shopkeepers who belonged to reform societies were boycotted by their customers, and in some parts of the country house-to-house enquiries were conducted to check the loyalty of individuals. Landlords of public houses refused to rent their premises to reform societies for their meetings. The Cambridge University Court expelled one of its dons for having published a pamphlet approving of the French Revolution. A Regius Chair of Chemistry was deferred because the only candidate was a supporter of reform.”

The fear of the ideas underpinning the French revolution was actively orchestrated by the Home Office. In addition to an established network of informants, the department’s policies included subsidising The Sun and True Briton newspapers to specifically promulgate fear of French subversion. Unsurprisingly, the general levels of fear among the population greatly increased. As Zamoyski writes:

“In the general panic, the Home Office and the Treasury Solicitors Office had begun employing spies to infiltrate reform societies and lurk in public places to report anything suspicious and gauge the mood of the public. In the second half of 1792, these began to send in reports of seditious talk, of expressions of discontent with the government and outbursts against the king, and even of people arming.”

One of the key insights established by Zamoyski in his examination of this period, is how unqualified the networks employed by the government and police were at their task, many reporting any discussion that began to sound slightly seditious, usually based solely on the informant’s own perspective.

The climate of fear haunting the European monarchies reached a peak on 23 March 1819, when Enlightenment philosophy was held responsible for Europe’s first act of suicide terrorism. In Prussia, Karl Ludwig Sand, a student from the University of Jena, entered the home of the renowned author August von Kotzebue, and after a brief conversation, stabbed him several times before plunging his dagger into his own stomach.

Klemens von Metternich, a German minister overseeing counter-enlightenment efforts, singled out for attention the role played by teachers, who he believed, “…can produce a whole generation of revolutionaries if one does not manage to check the evil.”

The repercussions of the killing were felt across Europe. The same year, Tsar Alexander of Russia ordered that the University of Kazan be cleared of all atheism and immorality, which led to the sacking of half the teaching staff:

“The library was purged of nefarious literature, beginning with Machiavelli and taking in all the philosophers of the Enlightenment and many contemporary German writers. Geology, deemed to be incompatible with the Bible, was removed from the curriculum, the teaching of mathematics and philosophy was curtailed, and priests were brought in to provide religious instruction.”

A Prussian minister, Karl Albert von Kamptz, warned that, “In France there were first Encyclopaedists then Constitutionalists, next Republicans, and finally regicides and high traitors. In order not to have the last types one must prevent Encyclopaedists and Constitutionalists from appearing and becoming established”.

This is a striking echo of the UK government’s current PREVENT strategy, which is premised on exactly the same notion: that there is a linear progression between ideas and violence; a notion exemplified by David Cameron’s July 2015 speech on Extremism, in which he declared:

“It begins – it must begin – by understanding the threat we face and why we face it. What we are fighting, in Islamist extremism, is an ideology. It is an extreme doctrine. And like any extreme doctrine, it is subversive. At its furthest end it seeks to destroy nation-states to invent its own barbaric realm. And it often backs violence to achieve this aim – mostly violence against fellow Muslims – who don’t subscribe to its sick worldview. But you don’t have to support violence to subscribe to certain intolerant ideas which create a climate in which extremists can flourish.”

Such rhetoric does not simply fail to understand the threats that we face today, from groups such as the Islamic State, but further fails to understand the history of grievance and violence that underpins the threats and responses today.

Time in the Shadows: European Responses to Anti-Colonial Political Dissent

Unlike Zamoyski, Laleh Khalili’s book, Time in the Shadows: confinement in counterinsurgencies (2013), does not shy away from drawing explicit parallels between the past and the present. Indeed, the very purpose of her book is to delineate the continuous trajectory of practices from the colonial period into the present day.

A large part of Khalili’s work concentrates on the concept of ‘confinement’ within the counterinsurgency strategies adopted by European and US governments. However, her book does also touch upon the way such strategies are situated within a wider ideological struggle, one that has racism and xenophobia built into its very structure. As Khalili points out:

“Racialisation of the enemy is crucial to liberal counterinsurgencies, in that ultimately a racial hierarchy resolves the tensions between illiberal methods and liberal discourse, between bloody hands and honeyed tongues, between weapons of war and emancipatory hyperbole.”

Much in the way of Europe’s response to the Enlightenment in the 18th century, the repression of civil liberties and basic freedoms became a mainstay of European and US government policy in the two centuries since. Khalili evidences, for example, legislation introduced by the French in Indochina specifically as a way of countering sedition:

“This ostensibly benign bout of “modernisation” and developmentalism had to be enforced at the points of bayonets and using the blunt instrument of the law. The Indochina criminal code passed in the 1890s…provided the tools for suppressing political dissent against French rule.”

What Khalili does so well throughout her work, is link criminal colonial practices, such as mass transportations to prison islands (Malta, the Seychelles, the Andaman islands and Guantanamo Bay), to counterinsurgency theories developed by the very people responsible for such crimes; showing in the process how modern day practitioners, such as David Kilcullen and John Nagl, had learnt from their forebears, notably David Galula.

Galula, was considered to be “the prophet of counterinsurgency”, having developed both its theory and practice while a French Army Captain in Algeria. His tactics were widely adopted by the French military and aided his swift rise into its key theorist. As Khalili notes:

“Galula writes that, early on in counterinsurgencies, a judicial system that is not stripped down through emergency measures allows far too much latitude for captured dissidents and guerrillas. Preemptive measures can alleviate this problem, in addition to surveillance and infiltration of the insurgents, thus “adapting the judicial system to the threat, strengthening the bureaucracy, reinforcing the police and armed forces may discourage insurgency attempts, if the counterinsurgent leadership is resolute and vigilant.”

Nagl’s position is equally stark:

“I’m not really all that concerned about their hearts right now…. We’re into the behaviour-modification phase. I want their minds right now.”

Although Galula and Nagl were referring to two different historical contexts –The effort to crush the Algerian rebellion in the 1950s and the U.S.’s attempts to win ‘hearts and minds’ in Iraq in 2004 respectively– they both understood that these were counterinsurgency operations to be implemented abroad, requiring the quelling of a majority indigenous population. Nevertheless, those very same principles have now been adopted for use in a domestic context, as European countries seek to deploy those very tactics to quell their own potentially seditious domestic populations.

Although Galula and Nagl were referring to two different historical contexts –The effort to crush the Algerian rebellion in the 1950s and the U.S.’s attempts to win ‘hearts and minds’ in Iraq in 2004 respectively– they both understood that these were counterinsurgency operations to be implemented abroad, requiring the quelling of a majority indigenous population. Nevertheless, those very same principles have now been adopted for use in a domestic context, as European countries seek to deploy those very tactics to quell their own potentially seditious domestic populations.

Indeed, the current UK government’s counter-extremism strategy seems to borrow a great deal from the ideas of past counterinsurgency efforts. For instance, the notion of “behaviour-modification” is at the heart of the UK government’s vision, once again focusing purely on the notion of ‘values’ rather than the grievances that underpin political violence.

One of the cheerleaders of this approach is Michael Gove, the neo-conservative Tory MP and author of Celsius 7/7, who asserts in the book that:

“The demands of national security are different from those of criminal justice, and governments have traditionally accepted the need for exceptional legislation and the temporary curtailment of liberties. We should be clear that these are needed again”

Gove’s suggestion is very much in keeping with British colonial practices, particularly in India during the late 1800s, where the Indian Muslim subject was treated with a great deal of suspicion.

The parallel is not accidental: It’s worth remembering that the British government responded to the Indian Sepoy rebellion of 1857 – a specific act of violence within a specific political paradigm – not by addressing the root causes of the rebellion, but by launching a commission, led by WW Hunter, into the “ideological struggle”.

By 1876, Hunter had published his findings, specifically highlighting the role of the education sector as a way of bringing about behavioural changes, particularly among the Muslim population. Predictably, Hunter saw the issue purely in ideological terms, ignoring the real wrongs and injustices felt by the Indian population under British rule. In his report, Hunter states:

“…we should develop a rising generation of Muhammadans, no longer learned in their own narrow learning, nor imbued solely with the bitter doctrines of their medieval Law, but tinctured with the sober and genial knowledge of the West …. No young man, whether Hindu or Muhammadan, passes through our Anglo-Indian schools without learning to disbelieve the faith of his fathers.”

In 1877, the Bengali weekly newspaper Som Prakash reported that schoolchildren were often heard discussing breaches of their human rights under colonial rule. Sudipa Topdar argues this “politicized ‘new child’ was seen in his/herself as seditious and how, “…confidential Education Department correspondences from the late nineteenth century warned of students discussing ‘seditious’ ideas…”

At that time, the Indian Penal Code Section 124A defined sedition so as to include:

“…words (spoken or written), signs or visible representations that brought or attempted to bring hatred, contempt, or excited disaffection (i.e. ‘disloyalty and feelings of enmity’) towards the Queen or the Government.”

This description is particularly interesting as it betrays the extent to which the British Raj was obsessed with the notion of ideas being particularly problematic, an obsession that has returned in the age of the “War on Terror”, except that what was once called “sedition” is today called ‘radicalisation’ or ‘extremism’.

With school-age children being increasingly politicised in late 1800s India, the British colonial project made the decision to stop the spread of such radical/seditious ideas within the schooling system itself. Topdar explains the ultimate purpose of this change in the curriculum and what it was intended to achieve:

“…the new policies ensured that textbooks of an ‘aggressive character’ generating hostile feelings towards the state were censored and substituted by ones imparting lessons on ‘state feeling’ and the ‘duties of a good citizen’. Here we see the colonial state grappling with remoulding the ‘seditious’ Indian child into a governable British subject-citizen.”

However, it was really in the year 1900 that the government began to aggressively pursue their proto-PREVENT strategy. After William Lee-Warner, Secretary in the British Political and Secret Department in the India Office reviewed the answer papers to the Bombay Matriculation Exams, he considered many of the answers to have a ‘seditious’ tone. Three institutions in particular were considered to be problematic in advocating seditious sentiments within the educational environment, notably by producing their own children’s books, such as Pushpavatika Balbodh and Tales from Maratha History, which were regarded as ‘apologies for disloyalties’.Topdar explains the objections over the Balbodh in particular:

“In most education records, serious objections arose about Balbodh regarding passages that criticized British rule for the economic ruin of India, for establishing a corrupt and racist judiciary where Englishmen could escape trial, and for ‘defiling Indian religions and insulting women’”

Far from reflecting a historical curiosity, these remarks seem eerily current. Indeed, it’s hard not to imagine today’s UK government taking issue with the content of these books.

The European response to the terror threat today, like that adopted within the context of colonialism, present no departure from the trajectory begun with the French Revolution. Rather, it is only the ideological target of the response – i.e. the type of ideas deemed contentious – that has changed: First it was the Enlightenment philosophy, then anti-colonialist ideas, then Communism, and now what policymakers term ‘Islamism’ or ‘political Islam’.

What is consistent across all of these perceived ‘threats’, is the methodology invoked in order to quell them, with the focus nearly always being on identifying and stopping a nefarious ideology.

Conclusion: Old wine, New bottles

Anti-revolutionary propaganda sheet from 1803 depicts King George III surrounded by symbols of British peace and liberty, while across the channel the figure of Napoleon is stalked by poverty and ‘universal destruction’ . (Source: The British Library)

The greatest moment of irony in Adam Zamoyski’s book is perhaps his passage on William Augustues Miles, the British minister in Frankfurt at the time of the French Revolution. Having taken exception to the revolutionary slogan of “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity” (a response to repression), Miles chose to illustrate the nature of his objection by invoking an Islamophobic trope of the time:

“[The French generals] Custine and Dumouriez, at the head of troops that know the value of victory, seem to be inflamed with a kind of zeal like that of Omar, and hitherto they have preached this new species of Mahometanism with a degree of success equal to that of the Arabian, … If the fury of these modern Caliphs is not successfully and speedily checked, every sceptre in Europe will be broken before the close of the present century, and the Jacobins be everywhere triumphant.”

That the same countries that later embraced the Enlightenment are today using precisely this same xenophobic and fear-mongering tone – including the Muslim threat – to rally their publics around an ideologically-rooted response to political violence, reveals a wilful refusal by Europe’s elite to learn the lessons of their own history.

In their own respective ways, both Zamoyski and Khalili offer us insightful new ways of thinking about European history that can and should inform our responses to events such as the attacks on Brussels and Paris.

Building a war around the notion that it is “values” that are under attack, and obfuscating the socio-political context within which ideas exist and operate, undermines our very ability to seek reasonable solutions to the issues.

The post-French Revolution period witnessed an era of extreme repression; including the suspension of habeas corpus, installation of the security state, and widespread suppression of civil liberties, ultimately leading to further disenfranchisement. During the colonial period, these measures were taken to a completely new level, as the principles of counterinsurgency became entrenched. The War on Terror has resurrected and redeployed many of these same practices, the latest being the ideological drive against ‘extremism’. Today, it is surely time, more than ever, to rethink the way we approach the issue of political violence, and to refuse to let our fear determine our response.

As Europe reflects on the latest tragedy in Brussels, we would do well to remember the words of Lord Burghersh, the British Minister to Florence:

“I am neither a Radical, nor that I have so far forgotten the principles which I have been brought up in, not to view with disgust the spirit of subversion and Jacobinism which is abroad; but I must at the same time declare that the system pursued by the Austrians in Italy, the ungenerous treatment of the Italians subjected to their government, will, as long as it is persisted in … not add one jot to their security!”

A fully-referenced version of this paper is available to readers on request.

2 Comments

Their Violence, Our Values: A History of European Responses to Political Dissent | CoolnessofHind

Their Violence, Our Values: A History of European Responses to Political Dissent – Veiled Suite

[…] Read here: Their Violence, Our Values: A History of European Responses to Political Dissent […]

[…] Source […]