Review: The Spanish Holocaust – Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain Books

Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Saturday, September 15, 2012 0:00 - 0 Comments

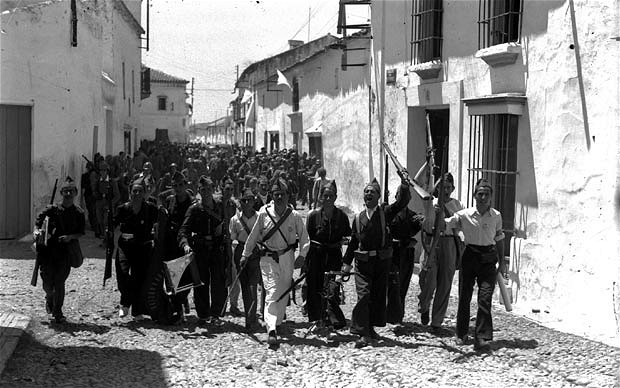

Falangist troops entering the newly captured town of Tocina, August 1936 (Photo: ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

In February 2003, as then-US Secretary of State Colin Powell presented the ‘case’ for the invasion of Iraq at the United Nations headquarters in New York, UN officials covered up a tapestry reproduction of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, hanging a blue curtain over Picasso’s searing anti-war depiction of the annihilation of the Basque town.

Although the reason behind the move remains unclear, it seems that this visual reminder of the horrors of the Spanish Civil War – the horrors, in short, of war – was not ‘on message’ with the calmly authoritative assertion that a country needed to be bombed, attacked and occupied.

The neo-con attempt to pull a clean blue curtain over a decade of horrors unleashed in Iraq may have ultimately failed. The history books have, however, been relatively kind to General Franco, all too often positioning him as a “soft” dictator next to contemporaneous fascist heads of state in Europe, while the decades since Franco’s death have seen both a sort of collective amnesia and memory-war of politicised-commemoration play itself out in Spain.

In his latest and most ambitious work, The Spanish Holocaust, historian Paul Preston lifts the curtain on the birth of Franco’s dictatorship by chronicling in exhaustive detail both the causes and dynamics of the Spanish Civil War and the methods of terror used to beat the civilian population into brutal submission. Although necessarily contested, estimations of the numbers killed remain shocking: perhaps 200,000 killed through firing-squads, tortures and ‘disappearances’. Preston takes on the fought-over statistics of lives lost as he brings to the fore the individual stories.

In case after case, cowardice and humiliation are recurring themes: forcing detainees to drink castor oil, shaving the heads of women and parading them around town centres, the frequent mutilation of corpses – the Dante-esque horrors, which drove some of those recording it insane, bubble up with the question of how such atrocities were papered over so quickly with the red-carpet pageantry of Franco’s ‘benevolent’ rule. As Preston writes, Franco had made a calculated investment in terror, reaping in his dictatorial years the advantages of a subdued, stunned-silenced population.

Part 1 of The Spanish Holocaust sews the nineteenth century history of Spain to the more immediate combinations of ideologies and pressures that married together into the climate in which the horrors of Spain’s 1930s were born.

Spain’s colonial legacy of systematic repression in Morocco fed back into the imperial centre as the returning Africanista military viewed the landless peasants involved in uprisings as ‘sub-human’ through the racist lenses honed abroad. Similarly, the agrarian oligarchy’s alliance with the industrial bourgeoisie became a crushing vice around a working-class who became identified in conservative eyes with foreign enemies.

Through the undertow of long-standing Catholic anti-Semitic sensibilities – that Spain was under threat ‘from within’ — a tortuous ideological alignment developed in conservative discourses. As Preston writes it, “Bolshevism was a Jewish invention and the Jews were indistinguishable from Muslims and therefore the leftists were bent on subjecting Spain to domination by African elements.” Such ideology-gymnastics that maintained belief in a ‘Jewish-Bolshevik-Masonic conspiracy’ bred the paranoia that unleashed itself in firing-squads, grotesque show-trials and purges.

The Spanish Holocaust does not shy away from the brutalities committed in the Republic, outlining the massacring of one third of all monks in Republic-controlled territory, and Preston admirably attempts to unpick the layering of half-truth over half-truth as each side developed its own mythology.

But central to the book is a delineation of the two types of terror unleashed: violence in the rebel zone is characterised as ‘institutional’, the heart of the system’s logic, while violence in the republican zone is characterised as ‘spontaneous violence’, the revolution eating itself in a climate where brutality was increasingly the only language of the populace.

Revenge – as a dynamic between the two main forces, as a motivator in villages and town-squares and between former friends – is the eternal-flame of the stories told here, from the purging of Navarre to the Column of Death’s march on Madrid.

As the analysis unfolds, Preston’s controversial and self-conscious use of the word ‘Holocaust’ is understandable, when taken on its own terms. Preston states explicitly in his Prologue that he does not wish to equate what happened in Spain with the Nazi extermination campaigns of the following decade, but that – as well as acknowledging the anti-Semitic rhetoric harnessed to incite the extermination of innocent Spaniards – the word ‘Holocaust’ captures the resonances between Spain and the horrors of twentieth-century Europe, pulling Franco’s name into line with these narratives and away from the blue-curtained respectability of the General’s ‘benevolent’ rule.

In its extensive documentation of what would now be termed rape as a weapon of war, the European heritage of Spain comes through in the evocation of the former Yugoslavia. While not meaning to minimise the specific factors of either conflict, the testimonies are distinctly reminiscent of the 1990s Balkans – European landscapes of illogical, Goya-ish horror, village-to-village massacres that mosaic into a wider and perhaps impenetrable memory-war.

In working extensively with local historians, and integrating the many monographs on regional aspects of the 1930s into his own archival work, Preston goes further than earlier English-language works, such as Anthony Beevor’s The Battle for Spain, in his attempt to hold the whole deck of cards in one’s hands, presenting a comprehensive, detailed and psychologically potent map of Spain’s descent into hell, and how the curtain was afterwards pulled over these horrors.

In working extensively with local historians, and integrating the many monographs on regional aspects of the 1930s into his own archival work, Preston goes further than earlier English-language works, such as Anthony Beevor’s The Battle for Spain, in his attempt to hold the whole deck of cards in one’s hands, presenting a comprehensive, detailed and psychologically potent map of Spain’s descent into hell, and how the curtain was afterwards pulled over these horrors.

The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain

Paul Preston

Publisher: HarperPress (1 Mar 2012)

Hardcover, 720 pages

Leave a Reply