Jean Baudrillard: Strategies of Subversion An A to Z of Theory

In Theory, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, September 7, 2012 22:42 - 2 Comments

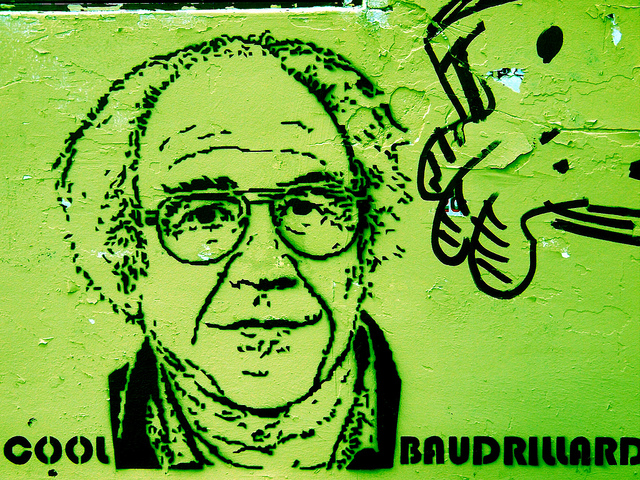

“In the field of language and signs, Baudrillard sees poetry, graffiti and seduction as types of alternative practice which create different ways of relating.” (photo: Patrick Giordano)

Alternative strategies to overthrow the code

Baudrillard proposes that opponents of the system replace explosive strategies with implosive strategies. Such strategies outbid the system in the direction in which it is already going, and/or restore symbolic exchange. Explosion responds to the order of production. Implosion and reversal similarly respond to the order of networks, combinations and flows. We live in an era when games of chance and vertigo have replaced competitive, expressive games. For Baudrillard, an effective subversion today would involve becoming more aleatory than the system. Baudrillard sees this as possible through ‘symbolic disorder’, the return of symbolic exchange. Death offers a higher order than the code, one which can move beyond and overthrow it.

Baudrillard argues for catastrophic – rather than dialectical – responses. Catastrophic responses involve pushing things to their limit. Catastrophe is not necessarily a negative idea – Baudrillard means catastrophe for the system, not for anyone else. Something is catastrophic in the bad sense only from a linear mode of thought. From another point of view, it is a winding-down of a cycle to its horizon or to a transition-point where an event happens. The catastrophe is the point of transition after which nothing has meaning from one’s own point of view. But the rejection of the code’s demand for meaning makes catastrophe no longer negative. Catastrophe is the passage to an entirely different world.

The challenge must now be taken up at a higher level. The challenge the code poses for us is the liquidation of all its structures, finding at the end only symbolic exchange. Baudrillard proposes that we ‘become the nomads of this desert, but disengaged from the mechanical illusion of value’. We should live this space, devoid of meaning, as a return to the territory, as symbolic exchange. To become, as one writer puts it, ‘the hunters and gatherers of the contemporary megacity’. We should reconstruct the current space as a sacred space, a space without pathways, while rejecting the seduction of value – allowing work, value, the dying system to bury themselves.

Baudrillard was writing this before the rise of contemporary surveillance and policing practices, which make it far harder to live in the system’s spaces as if they were territorial. It seems the system has somehow gained a reprieve from death, as it has several times before. It has done this by further deepening and expanding the code, and by drawing on reactionary and fascistic energies.

According to Baudrillard, the challenge is to avoid fascination with the death throes of the system, to avoid giving it our energies in this way – to simply leave it to die. The system keeps itself alive by staging the ‘ruse’ of its death, while leaving the subjects it has created intact. It is, rather, through our own ‘death’ (or metamorphosis) that the system collapses. With the social failing, it seeks new energy, drawing on the marginal rebellions of excluded groups. For this reason, Baudrillard is suspicious of attempts to recreate marginal systems of meaning, instead calling for the logical exacerbation of the system’s logic.

One part of this revolt is the recreation of direct relations. The code depends on everything being segmented and reduced to it, hence separated from others. Where exchange happens – for instance, direct communication in a liberated area – the finality of the code is shattered. Any kind of social practice or language which does not rely on the distinctions made by the code is revolutionary. Connections between people which don’t depend on their social status, solidarity across social borders, is revolutionary.

Baudrillard also calls for the expansion of ‘pataphysics‘ – the formulation of imaginary solutions and problems in parody of science, similar to Situationist detournement and post-Situationist subvertisement and culture jamming. One might also see phenomena such as Internet memes as pataphysical. For Baudrillard, pataphysics is a further stage beyond simulation, which raises the stakes on it.

This leads to particular implications. The revolutionary aspect of emancipatory movements (say, of Tahrir Square or the Argentinazo or Occupy) does not reside in their demands or significations, but in their existence beyond these, as direct connection. The real struggle is always against the code. But the system defuses or recuperates struggles by redirecting them from the code to reality. This turns them into struggles within the system. It also deflects them back to the field of political economy.

But the reality we experience is a product of the code, and political economy is now an illusion. What seems to most people as a fulfilment of a movement – the realisation of its particular project – is for Baudrillard a recuperation, a loss of the alternative forms of sociality it produces. A thoroughgoing revolution would keep up constantly the intense connections of a liberated zone. It would thus become something akin to a new indigenous group, constructed through symbolic exchange.

Poetry, Graffiti, Seduction

In some passages, Baudrillard proposes alternatives to the language of the code, which can restore other forms of social relations.Changes in media content are assumed to have little effect. Rather, effective changes alter the form of media. In the field of language and signs, Baudrillard sees poetry, graffiti and seduction as types of alternative practice which create different ways of relating.

Poetic language is the form of symbolic exchange within language. This is because it is not reducible to the expression of the code. It renders language open to being broken down into its particular components – like in Freirean education. It is therefore opposed to language as value, and to identity. According to Baudrillard, in the dominant language, elements are accumulated as dead weight because they are never symbolically destroyed.

Poetic language creates a kind of vertigo, leaving the place of the signified empty. It is the force which destroys the code. Baudrillard thus sees poetic language as non-representational. It implies reversibility. It escapes the fate of language to silence and separate, allowing ambiguity. This view is advanced against the idea of poetry as simply a loosening of fixed meanings (the position taken by most poststructuralists). In Baudrillard’s discussions of poetry, a special place is reserved for Baudelaire. Baudelaire’s art is praised as enchanted, ironic, ecstatic, repeating and exceeding the logic of the system. Irony is seen as an expression of the indifference of the object.

Baudrillard also provides an interpretation of graffiti, particularly the kind involving tagging. He sees it as a ‘savage offensive’ in response to the enclosure of people and signs in ghettos. The city encloses people in the form of the sign, or the code. Ghettos cut-up social life, downgrade particular lives, and symbolically destroy social relations. Graffiti exterminates this space of the code by exceeding the code in its non-referentiality: a tag refers to even less than the code does. Tags are an anti-discourse of empty signifiers, often borrowed from comics.

In resistance to the proper name and private individuality of capitalism, graffiti writes ‘tribal’ names with symbolic force. They territorialise spaces which have been decoded by the system, turning areas into collective territories. These signs are quasi-anonymous, and they can be given and exchanged freely. They dismantle or scramble the signals of the order of signs. They resist both assigned identities and impersonal anonymity.

This resistance repeats the system’s own simulations. Graffiti tags reproduce mass relations in that they allow no response. But they are subversive because they simulate symbolic exchange, play, and non-functional space. They avoid any reference or origin, consisting of nothing but names, and with no message. (Trying to interpret graffiti as art or as expression of identity is for Baudrillard recuperation). This, for Baudrillard, provides a model for resistance. To dismantle the network of codes, we need to attack coded difference. The means to do this is through an uncodeable absolute difference.

Baudrillard also writes of reinventing the power of illusion and seduction, the power ‘to tear the same away from the same’, to invent signs which point nowhere, to master the art of escaping chance and causality and causing disappearances. Obscenity and seduction are closely related. Hence, Baudrillard is almost talking about acquiring the same power the system has obtained, to create pure images which exist beyond binaries. Yet he is also talking about recreating the scene, the type of illusion the system has destroyed. He distinguishes seduction from fascination. Seduction has something in common with passion, with the ‘hot’ sphere which is lost. It is an art of withdrawing something from the visible order – and hence counterposed to liberation and production.

It also recreates the experience of destiny. The fetish performs a miracle of summoning an experience of destiny from the accidental nature of the world – fate instead of chance. It creates a world which is connected, rather than aleatory. Things have a predestined linkage. Connections occur through the cycle of metamorphoses. Fate happens because everything seems to be linked to everything else, without exception. One can experience oneself as being a decisive element in a situation without willing it – as being indispensable. Such unexpected connections can at most be imitated by strategy. They escape the rule of the code. They take us into a world which is neither random nor causal, instead resting on the equivalence of the signs of emergence and disappearance.

Seduction brings things outside their objective or rational causal connections, instead connecting them by arbitrary signs or codes. However, they do not seem arbitrary. They are experienced as destined. This reverses cause and effect. Effects seem to generate their causes. Neither a chance-based nor a causal world is as appealing an idea as a world ruled by willed or destined coincidences. From a symbolic point of view, a neutral world is repugnant. Destiny thus exists in a Manichean conflict with causality and chance.

In seduction, the experience of events is altered. One experiences a pure event rather than a rational sequence. In a pure event, one experiences oneself as a thing rather than a word (e.g. as an embodied self rather than a rational ego). This event needs to be transmuted further, into a spectacle or scene with a magical effect, beyond representation and causality. And it blurs the barriers between Good and Evil. People secretly desire the unravelling of rational connections and their replacement with events, in which things come together spontaneously in a single site of intensity. Such experiences can be created through unexpected connections.

Seduction is antagonistic, like a duel. It is counterposed to the ideal of universal love. It thus restores symbolic exchange. Baudrillard suggests that love is part of the Christian defeat of symbolic exchange and the fall into individuation. It is connected to the ‘maternal’ and the Oedipal family. It is an imaginary replacement for the actual loss of connections. Its loss or absence today is cruelly felt. To love, according to Baudrillard, is to isolate someone from the world, and dispossess her/him of her/his secret or shadow. Love consists of a floating libido which tries to invest its environment in a cold, dispassionate way. It can be manipulated by the code because it floats in this way. Baudrillard is advocating, against this ‘cool’ form of desire, a return to the ‘hot’ intensities of seduction and passion. He also argues that seduction is more basic than sex or the orgasm.

To seduce something is to return it to the cycle of appearance and disappearance, hence of metamorphosis. There is a void behind power. Seduction and reversibility causes it to collapse. In seduction, the object is seductive. The subject dominates the object, but the object can reverse this domination. Signs become simply a game of appearances, rather than referring to an absent reality.

The ontological status of destiny in Baudrillard’s argument is often unclear. Baudrillard’s argument seems to be that it is best for us to believe in destiny, and act as if it exists. He argues for it from its emotional appeal and its role in societies with symbolic exchange. It is the way in which signs obtain intensity, and hence a counterpoint to the ‘cool’ signs of today. He also argues that everything is of the order of initiation and symbolic exchange, since everything comes into being and disappears.

Crucially, seduction reverses the usual power of the subject over the object. The object traps the subject through seduction, and drags it down to annihilation. Seduction has the effect of making a particular sign or object no longer arbitrary. Signs become objects become impossible to turn into metaphors. This, presumably, stops the interchangeability of the code, creating a particular existential territory or connection. The object is always the master of the game in seduction. Seduction aims for a kind of contact as if in adversity, which carries out a magical integration of what is otherwise distinct.

Seduction is the reversal of production. Production brings things into existence, whereas seduction makes things disappear, after initiating them into a different type of existence. Seduction is governed by a secret rule, hidden behind and counterposed to the law. It renders a subject unidentifiable to him/herself. This kind of subjective transformation presumably destroys the hold the system has on people, creating a new kind of being. “Object” in Baudrillard has implications of something being undivided or not segmented (prior to the subject-object split or the posited origin of the subject in language). Yet seduction is also recuperated in consumer society as ‘cool’, de-intensified seduction.

Seduction also produces a kind of social and ecological fusion. Whereas psychoanalysis or the law tears one from one’s earlier fusion with the world to be placed in a situation of individualised desire, seduction tears one from individualised desire and the realm of interpretation and returns one to fusion with the world. One sidesteps exploitation by moving into a different model of the world.

This view of Baudrillard’s has been criticised as a mystification of gender-relations, particularly of the objectification of women. Suzanne Moore, for instance, has called him the “pimp of postmodernism”. Baudrillard values precisely those aspects of sexual and romantic relationships which others increasingly pathologise as manipulative or emotionally abusive – treating the other as the source of one’s emotions, making the other define oneself, and so on. He has a tendency to see people on the receiving end of obsessive attachments as actually being seducers, or being allowed by others to abuse.

Despite the problematic repetition of patriarchy in Baudrillard’s work, he is not seeking to promote an unreconstructed masculinity. Baudrillard celebrates women’s power, and views a return to seduction as a positing of feminine against masculine logics. Yet the feminine power he celebrates is a power arising from the status of being an object for the male gaze. This puts Baudrillard on a collision-course with many varieties of feminism. He sees feminism as hostile to or ashamed of seduction, and as part of the fallacious pursuit of the liberation of a repressed essence. Baudrillard doesn’t seem to perceive the close relationship between objectification and trauma. He turns objectification into a source of power all too readily, without understanding the feelings of powerlessness it often entails.

There is also an authoritarian aspect to his theory. Baudrillard sees symbolic language as primarily laying out rules. These rules have no basis – they simply command and direct. They steal one’s liberty, since they determine one by one’s fate. For Baudrillard, people prefer an order which leaves no choice to one which makes them realise they don’t know what they want, producing indifference. This is the case even if a large part of the appeal is in the subversion and transgression of this order.

For Baudrillard, there needs to be separation into categories, and ‘discrimination’, to prevent an impoverished and confused world. There needs to be a culture which separates human groups from nature, separates the initiated from the uninitiated, overcomes the confusion and interpenetration of ideas and things, separates what follows a rule from what doesn’t. For Baudrillard, this discrimination and separation is a central function of theory. It creates a power of metamorphosis and illusion. (On another occasion he suggests that the central goal of theory should be to make the world more enigmatic and difficult to understand).

This can sound dangerously close to a call to restore symbolic order against the chaos of floating meanings. It can read a bit like a Hobbesian position applied to language – without a strong order restricting meanings, everything seems confusing and chaotic. I doubt this is what Baudrillard has in mind, but it arises from certain limits to his theory – in particular, his Lacanian view of the psyche.

However, it is more helpful to think about symbolic exchange in terms of the recovery of the communion or fusion arising from a ‘fused-group’ type of social formation. Elsewhere, Baudrillard questions whether the symbolic requires a master-signifier. It might be suggested that the bund or neo-sect is an alternative which is neither authoritarian nor indifferent.

[Part Twelve will be published next week. Click here for other essays in this series.]

2 Comments

Nick

Jean Baudrillard: Strategies of Subversion | Ph...

[…] Having previously explored why Baudrillard rejects the traditional account of revolution, Andrew Robinson this week examines the French thinker's alternative proposals for resistance, including Baudrillard's theories of catastrophe, poetry and seduction. […]

This is the last entry in this series that I can see. There has been continuous problems trying to access this series. Sometimes the “in theory column” page has no new entries and the front page does. Other times I found the latest one by searching around for ages. Now part 12 simply has not appeared. It is such a shame that these fascinating essays are not displaying properly. I hope you can sort out whatever technical issues you are having with your website soon soon so I can read more of this. This piece was posted on 7th September and there simply hasn’t been anymore entries available. When I look at this site through different devices and computers the problem remains the same.