Africa, racism and the West

Features, The Anti-Imperialist - Posted on Thursday, November 26, 2009 0:03 - 0 Comments

US military intervention in Africa, writes Adam Elliott-Cooper, is premised on a Western understanding of a global racial hierarchy in which Africans are at the bottom.

US military intervention in Africa, writes Adam Elliott-Cooper, is premised on a Western understanding of a global racial hierarchy in which Africans are at the bottom.

Racism has been endemic in Western foreign policy for centuries. When the Spanish arrived in what they called the ‘West Indies’ in 1540, they saw the indigenous people as vermin – no life was worth sparing. A critic of Spanish colonialism in the ‘New World’, Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566), described the actions of the settlers: “All those captured – pregnant women, mothers of newborn babies, children and old men – were thrown into the pits and impaled alive”.

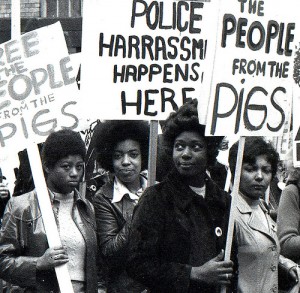

The relevance of race and racism has not been prominent in the study of international relations, despite glaring differences in economic and military power between the predominantly white ‘North’ and the overwhelmingly black ‘South’. Colonial legacies, which have left destruction and suffering in their wake, have been exacerbated by economic policies unimaginable in Europe or the USA.

The inhuman treatment of non-Europeans, the global majority, simply because they stand in the way of economic resources or military gains, has been standard practice for the makers of Western foreign policy. Hundreds of years after de las Casas wrote of the horrors of colonialism, those of European descent continued to enslave, plunder and exterminate indigenous peoples around the globe. As Kipling described it, this was their burden: “Send forth the best ye breed/ Go bind your sons to exile/ To serve your captives’ need”.

European racism was of course resisted, and its criticism was published in western literature as soon as non-Europeans gained access to the Western media. The most notable exposition of the effects of racism on the psyche of both colonisers and colonised is found in the works of Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) and Edward Said (1935-2003). These fathers of postcolonial studies developed a crucial framework for the understanding of Western intervention in Africa. Fanon highlights the contradictions of colonialism as follows: “Black Africa is looked on as a region that is inert, brutal, uncivilised” even though “[d]eportations, massacres, forced labour and slavery have been the main methods used by [western] capitalism to increase its wealth . . . and establish its power [in Africa]”. Even today, Europe and the USA profit greatly from goods that are sourced under slave-like conditions (such as sweatshops) – yet they rarely question their own morality in intervening in conflicts in which they have often helped to start or exacerbate.

The Somalia case

In 1992, Somalia was dubbed a ‘failed state’ by Western academics, citing the breakdown of Western-style political institutions and infrastructure. This judgement led the US-led UN task force to claim that they could restore law and order (helpfully ignoring the fact that Said Barre, the ruthless dictator spreading violence and suffering across Somalia, had been backed, funded and militarised by the US ever since he had come to power.)

In 1992, Somalia was dubbed a ‘failed state’ by Western academics, citing the breakdown of Western-style political institutions and infrastructure. This judgement led the US-led UN task force to claim that they could restore law and order (helpfully ignoring the fact that Said Barre, the ruthless dictator spreading violence and suffering across Somalia, had been backed, funded and militarised by the US ever since he had come to power.)

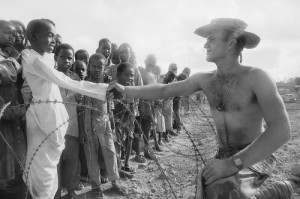

Somalia was the first external military intervention in Africa since the end of the Cold War. The country had been fought over by the US and USSR a number of times via proxy wars in the postwar period, and the US saw the 1992 intervention as a chance to assert dominance as the global superpower in a unipolar word. Noam Chomsky dubbed it “a PR operation for the Pentagon”. Such a PR operation could only be conceived in a framework of US superiority: Africans were perceived as different to people of European descent – the ‘other’.

The ‘good intentions’ of the US mission in Somalia are usually stressed. The US mission statement was described by Chester Crocker, former Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, as a “sweepingly ambitious new ‘nation-building’ resolution”. But what made the US think they had the power to enter a country to stop a civil war and end a famine? More importantly, what made the US think they had a moral superiority over the Somali people that qualified them to determine the way in which their state was run? The US government dictated to the Somali people (and to the rest of the world) who they would install as the new leader of their country. Edward Said sums up this mentality as “the universal discourse of modern Europe and the US” who “assume the silence, willing or otherwise, of the non-European world”. Such sentiments are reflected in mainstream Western media: the Wall Street Journal despairingly states that “modern day colonialism may be the only policy that can prevent more tragedies in Somalia, and perhaps elsewhere in Africa”. This paternalistic attitude towards Africans is a further indication of the racism that has been burned into the minds of the American mainstream.

A further US attack on Somalia killed four people and wounded 20 in early 2008. The Pentagon claimed they were targeting a known al-Qaeda terrorist inside Somalia – yet despite the attack constituting a clear breach of international law, the US was not subject to any investigation. In fact according to the BBC, the US Defense Department spokesman Bryan Whitman “refused to give the identity of the target, whether the strike had achieved its goal or how the strike had been carried out”.

Such arrogance and contempt for international human rights serves as an expression of the racial superiority that international actors of European descent feel they have over Africans. Such apologias for neo-colonialism – including bombing raids in the name of national security – are entrenched in western media.

9/11 and Sudan

It is often stated that national security concerns justify pre-emptive action as part of the so-called ‘war on terror’.

It is often stated that national security concerns justify pre-emptive action as part of the so-called ‘war on terror’.

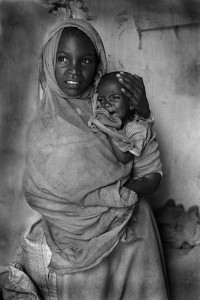

In 1998 the US bombed and destroyed a pharmaceutical factory in Sudan called al-Shifa, which was the main source of anti-malarial and veterinary medicines in the region, and essential for a predominantly agricultural country with many health problems (due, in part, to the ongoing conflict).

The US government insisted that the attack, dubbed ‘Operation Infinite Reach’ was a response to attacks on US embassies in Tanzania and Kenya a few days earlier. They also claimed that the factory was producing a VX nerve agent (classified as a WMD by the Chemical Weapons Convention) and that the owners of the medicine factory had ties with al-Qaeda.

The allegations of VX nerve agent production came from a CIA operation that found EMPTA (a compound used in VX) in a single soil sample taken from outside the factory. However, as EMPTA is also used in the production of industrial products such as plastic, it is therefore not banned under the Chemical Weapons Convention. As the New York Times notes: “Officials later said that there was no proof that the plant had been manufacturing or storing nerve gas, as initially suspected by the Americans, or had been linked to Osama bin Laden … no apology has been made and no restitution offered.”

It is impossible to say how many Africans died as a result of the ensuing shortages of human and veterinary medicine (the few serious estimates put the number at many thousands). But this is obviously beside the point. As Noam Chomsky points out, the ruling political elite in America uses such military forays to enable it to ignore popular calls for reforms such as for a state-based universal health service, improved schools or job creation.

Yet such diversion would not be possible if there did not already exist an underlying assumption of US moral and intellectual superiority in a global racial hierarchy. The implementation of foreign policy, from ‘humanitarian’ military intervention to the ‘war on terror’, can be – and is being – used as an effective tool in diverting the attention of western populations away from the problems in their own countries.

The destroyed lives of Africans are, at the most, little more than a slightly unpleasant afterthought.

Leave a Reply