It’s not just about tuition anymore… Quebec Chronicles

New in Ceasefire, Politics, Quebec Chronicles - Posted on Saturday, June 2, 2012 0:00 - 0 Comments

Posters in Montreal’s Latin Quarter, designed by UQAM’s École de la montagne rouge collective. Visual references to the conflict are unavoidable in most of the city, where the student movement’s red square symbol is everywhere. (photo: Jane Gatensby)

In the streets of Montreal, there is a palpable feeling that something important is happening. This May, Quebec experienced a powerful wave of mobilisation, as citizens responded to a far-reaching emergency law aimed at putting an end to the carrés rouges’ now 16-week long student strikes. Backlash against the law has led to the politicisation of thousands in nightly casserole protests.

As a result, what was once just a fight over tuition hikes of $1778 for Quebec university students has evolved into a popular movement for the preservation of fundamental civil liberties, and is having a profound effect on the political climate here. Though a resolution to the conflict still seems far off, its designation as Quebec’s printemps érable (maple spring) is becoming more and more accurate.

Victoriaville

The month began violently, as May 4th’s Quebec Liberal Party general council meeting in Victoriaville was descended upon by as many as two thousand people, coming in from all over the province by bus. The event was marked by one of the worst riots since the start of the conflict, as protesters armed with rocks and billiard balls clashed with police, who responded with tear gas, rubber bullets, and batons. Eleven people were wounded, including four police, and entire busloads of protesters were arrested.

Rioters at Victoriaville (Source: Nicolas Quiazua)

Back inside the convention, as the smell of tear glass wafted in through broken windows, Premier Jean Charest addressed his deputies with confidence. Dismissing his opponents for wanting to “run Quebec on freezes and moratoriums”, he affirmed that his party would take the hard line.

Scrambling for a solution

Following a second unfruitful attempt at negotiations with student federations, Line Beauchamp, Quebec Education Minister and frequent object of the strikers’ derision, stepped down on May 14th. She was replaced by ex-Education Minister Michelle Courchesne, who oversaw the previous round of hikes in 2007.

By the second week of April, university and cégep administrators had serious doubts about the feasibility of finishing the semester. Injunctions brought forth by individual students against hard picketers continued to spark conflict on campus, and further complicated the scheduling mess, as some classes would go on with only a handful of students attending.

On May 18th, with the new minister by his side, Charest took new and drastic measures to bring an end to the strikes, passing a far-reaching emergency act entitled “An act to enable students to receive instruction from the post-secondary institutions they attend”. The new law, commonly referred to as “la loi spéciale”, sparked public outrage, and breathing new life into the protest movement.

Law 78

The law begins by immediately suspending the semester for the 11 universities and 14 cégeps (colleges) still on strike and scheduled it to resume in August, requiring students to inform their schools on whether or not they will be attending the resumed classes by June 15th. It bans hard pickets on campus outright.The message is clear: students do not have the right to go on strike. If student associations don’t comply, the ministry can cut off their funding; student associations are also liable for any personal losses that might occur from the non-respect of the law.

More controversial, however, are the bill’s’ “Provisions to maintain peace, order and security”. They require the organisers of any demonstration of 50 or more people to inform police of their planned location and route eight hours beforehand, and the law allows police to demand a change of venue or route. Individuals can be fined $1000-5000 for violating the law, and student associations can be fined up to $125,000. Additionally, anyone who “helps or induces” another person to break the law can be charged with the same offence, raising questions about the law’s implications for freedom of expression.

The law received harsh criticism from the legal community. Louis Masson, president of the province’s Bar Association, said that the it risks scarring “the integrity of our fundamental rights”, and Amnesty International said it “goes far beyond what is permissible under provincial, national or international human rights laws”.

Hundreds of lawyers march against Law 78. (Credit: André Pichette, La Presse)

The Coalition Large de l’Association pour une Solidarité Syndicale Etudiante (CLASSE), known as the most radical of three major student federations, immediately denounced the law and launched an online “someone arrest me!” campaign, calling for civil disobedience.

Law 78’s passage marked the beginning of an ugly few days of night protests (“manif chaque soir”, a practice that has been going on since mid April) in Montreal, where organisers refused to unveil their plans to police as an additional act of protest. Despite the risks, marches in the days following the law’s passage were attended by large numbers of students and, before things calmed down (it took about a week after the bill’s passage), the protests included molotov cocktails and heavy objects thrown at police, a bonfire of traffic cones, chemical irritants, and plastic bullets, and hundreds of arrests, including a mass kettle of 500 on the 23rd.

As of May 25th, 2500 arrests have been made across Quebec in connection with the conflict. The majority of those arrested in connection to Law 78 and the municipal anti-mask plan to contest their tickets in court. Civil rights challenges to the law have a chance of winning: the United Nations said this week that it “unduly restricts the right of association and peaceful assembly in the province”.

More arrests occurred at a daytime protest on May 22nd, when tens of thousands of people marched in downtown Montreal to mark the hundredth day of student strikes. The march split into multiple groups, with the contingent led by CLASSE choosing not to reveal its route to the authorities, and experiencing clashes with police. The event was otherwise peaceful.

As demonstrators walked home from the march, they were greeted with a large racket. Inspired by cacerolazo protests in Chile, families in many of Montreal’s residential neighbourhoods had come out onto their porches and balconies to bang pots and pans against the bill. The practice, come to be known as les casseroles, has since spread throughout the province, gaining participants by the day.

From casseurs to casseroles

A viral video showcasing the casseroles protests. (Credit: Jeremie Battaglia)

Although many of these new protesters are also against the hikes, most wouldn’t have mobilised if not for Law 78. Demographically diverse, the casseroles gain much more sympathy among the Quebecois than the student night marches known to include the casseurs, associated with vandalism and violence.

Montrealers were also annoyed at the disruption caused by student demonstrations in general (smoke bombs set off in the Metro this month didn’t help matters), but things have changed now that regular people, neighbours, are risking arrest every night in the name of civil liberties. The casseroles soon became a pacifying force at the night demonstrations, ennobling the cause and rendering Law 78 practically unenforceable.

Seen from afar

Quebec personalities bring red squares to international audiences: Xavier Dolan at Cannes and Arcade Fire on Saturday Night Live.

The month also saw Quebec’s profile raised on the international stage by the conflict. With links established between Quebec’s student movement and student protests in Chile, the province is being seen as one of the hot spots of a global protest movement.

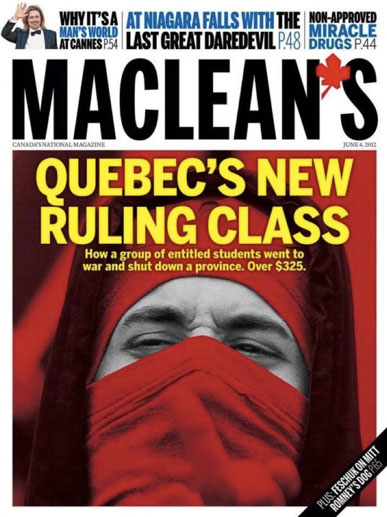

Simultaneously, the crisis is showing the enormous chasm of understanding between Quebec and the rest of Canada, where large-scale mobilisation like this simply does not happen. The Rogers Communications company’s L’actualité and Macleans magazines, two widely-read general interest weeklies that serve Quebec and English Canada respectively, each ran the conflict on their cover this month, to very different effect:

In anglophone Canada, where public tuition can cost over $6 500 a year, commentators are often baffled by the movement, and have largely responded by belittling the protests, with a fair bit of Quebec-bashing thrown in. Both writing from Toronto, The National Post’s popular commentator Rex Murphy referred to the movement as a “self-indulgent fit”, and The Globe and Mail’s Margaret Wente called protesters “the Greeks of Canada”. A similar view was expressed in an article published in The Economist on May 5th,entitled “Free Lunches, Please”.

The students-are-spoiled-brats-who-don’t-know-how-good-they-have-it argument, which is often expressed in Quebec’s francophone news outlets as well, was responded to poetically by filmmaker Xavier Dolan, who had come under fire from a Journal de Montréal columnist for having put Quebec’s “family squabbles” out on display by wearing a red square to the Cannes film festival.

“When we look inwards we find fault, when we compare ourselves to others, we find consolation”, he said in an open letter to the columnist in question. In other words, those who justify the hikes by comparing them to the North American norm are ignoring the part of debate that centers around whether or not Quebec would be better off if education was paid for collectively.

The big(ger) picture

While the carées rouges try and block the hikes and the casseroles denounce the law, a third struggle is interwoven through the movement, that of the “bien commun”, a term signifying both public wealth and public interest. More and more, people are criticising Quebec’s recent slide towards the neo-liberal norms of its North American neighbours. As Université de Montréal professor Christian Nadeau put it in a recent open letter to students, Quebec is seeing a “return of the social-democratic tide”.

The student movement has long spoken out against the education-as-product, student-as-consumer trend in the province’s universities, denouncing sky-high advertising budgets, corporate-funded research, and golden parachutes for departing rectors. But as Le Devoir’s Éric Desrosiers reported last Saturday, a whole host of additional issues have entered into the debate, as Quebec ponders what kind of society it really wants.

The protesters’ cries for free education marry well with many Quebecers’ outrage over rising inequality and the mismanagement of public funds, and consequently, government policies that let the province’s resources be used to make private corporations richer, like last year’s shale gas debacle or the Plan Nord, are being called into question by large numbers of mobilized students and citizens.

In the same vein, this month saw the beginning of Quebec Justice France Charbonneau’s public inquiry into corruption in Quebec’s construction industry, meant to shed light on the allegedly widespread problem of bribes made to public officials by companies trying to obtain lucrative contracts.

The Quebec Liberal Party expected to suffer from the scandal. To quote sixty concerned law professors, the tension around Law 78 is particularly high because it comes at a time when “the confidence of citizens in several of the large public institutions forming the backbone of our society seems greatly weakened” because of corruption.

Montreal Mayor Gerald Tremblay, who has criticised the movement for its negative effect on summer tourism and who spearheaded the anti-mask bylaw, saw three close former political collaborators, including the ex-chief of Montreal’s executive committee, arrested this month in relation to a bid-rigging scheme.

As another month of strikes and protests drew to a close, higher stakes brought the government and student federations to the bargaining table for the third time, but with tensions still very high, talks fell through once again on May 31st.

Furthermore, CLASSE’s co-spokesperson, and the movement’s most famous face, Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, may face up to one year in prison for allegedly encouraging students at Laval University to disobey an injunction banning hard pickets on campus last month.

No one is quite sure what will happen when classes resume in August, or whether Law 78 (which will remain in effect until July 2013) will be found to be legitimate when those charged have their day in court. What is becoming clear, however, is that Quebec society is at a crossroads, and the conflict is going to have a profound effect on the direction it takes next.

Leave a Reply