Turkey: “So much space in this courtroom, yet so little room for justice” Special Report

Features, New in Ceasefire, Special Reports - Posted on Monday, July 22, 2019 18:18 - 0 Comments

By Milena Buyum

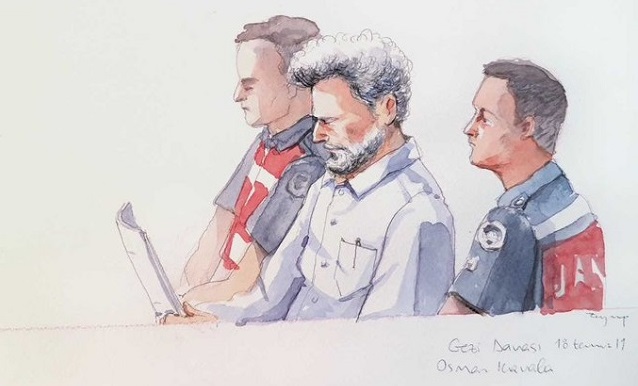

Artist rendering of Osman Kavala at his trial this week. (Credit: Zeynep Atalay)

“This courtroom is 1,000 metres squared and the public gallery has space for 500 people,” the clerk tells me with pride. “It has 200 seats for lawyers and 250 for defendants.” The numbers send chills down my spine. This is a courtroom designed for mass trials.

I am in the gargantuan courthouse that squats behind the walls of the Siliviri high-security prison, the largest jail in Europe. I’m here to observe the start of the second hearing of 16 Turkish civil society figures, including the prominent figure, Osman Kavala.

Osman Kavala has been in pre-trial detention in the Silivri since November 2017. He and 15 others are facing absurd allegations of masterminding the Gezi Park protests in 2013 and ‘attempting to overthrow the government of the Turkish republic or to prevent it from performing its duties’. If found guilty they face life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

I arrive in the courtroom early and watch as the immense space fills up with observers, journalists, lawyers and defendants. Suddenly, there is loud applause. Osman Kavala has entered, surrounded by a scrum of 15 or more prison gendarmes. Two on each side hold him under the arms. He turns to us as he approaches the dock, smiling and attempting to raise a hand to wave. When he sits, the gendarmes remain on their feet on either side of him, blocking his view of family and colleagues.

We all stand as the three judges and the prosecutor enter and take their seats. The president of the panel of judges announces that, although the hearing is scheduled to last two days he would like it to be over in one. “I have other cases to attend to tomorrow,” he says. I wonder if this is a sign that Osman Kavala might be released today.

First, the case for the defence is presented. Lawyer after lawyer explains in detail why the 657-page-long indictment does not contain the evidence required to justify the charge: “For the basis of the crime outlined in Article 312 to have occurred, there has to have been a clear and imminent danger,” explains one lawyer. “In criminal law, there has to be the continuum between criminal act, suspect, evidence; these three have to be connected. This indictment is not bothered with providing such links. Instead, it simply presents every dissenting act as crimes.”

He goes on to explain that the article under which they have been charged requires there to be coercion and violence. “It is not enough to have founded an organisation,” he explains. “This organisation has to be an armed group.”

Then Osman Kavala — as the only imprisoned defendant — is called to address the court. “There is not a shred of evidence in the taped conversations that I have had a role in organising the Gezi Park protests,” he says. “No evidence that I participated in any meetings or gatherings that involved violence. On the contrary, I played the role of the intermediary between the protesters and the authorities, to change the course of events towards a peaceful conclusion. I was not questioned after the Gezi Park protests. When I was first detained, the only question I was asked regarding Gezi was about a photo exhibition in Brussels and two photographs I had on my phone. It took 16 months to prepare this indictment devoid of any evidence. I have now spent 21 months in prison. I request my release from prison.”

His impassioned appeal is met with long, sustained applause and I find myself thinking: “He will be released today, and this absurd ordeal will be over.”

The prosecutor then stands. He goes through the defendant’s requests one by one and, in a monotonous tone, asks that they be rejected. He offers no justification for his requests, no challenge or legal argument, at all.

His short intervention makes me wonder whether he has listened to anything that was said over the past six hours as the defence lawyers had systematically dismantled any justification for their prosecution.

The court adjourns, and Osman Kavala is led away, surrounded by gendarmes. We are told to clear the courtroom. Only international observers, diplomats, MPs and family members will be allowed back in to hear the interim decision of the court.

After about 30 minutes we file back into the now empty courtroom. I feel a tight knot of tension in my stomach. I can only guess how Osman Kavala’s wife is feeling.

We stand for the judges. The president of the panel of judges then reads out what he says is “a majority decision.” All the defendants’ requests have been rejected. Osman Kavala will remain in prison. By the time of his next hearing he will have been behind bars for almost two years, a very long period of period of pretrial detention even by Turkey’s terrible standards.

I feel the hope that I had allowed to build, disappear. I look around the vastness of this courtroom: so much space, and yet so little room for justice.

Leave a Reply