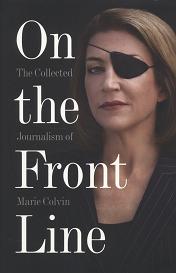

Review | On The Front Line: The Collected Journalism of Marie Colvin Books

Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, March 8, 2013 0:00 - 1 Comment

Marie Colvin’s death in Syria in 2012 was iconic – the image of the war correspondent with the eye-patch travelled around the world – but in her reportage, collected in the lengthy paperback volume ‘On The Front Line’, her real achievement as a writer and journalist was in how she captured the ordinary details, daily dramas and telling moments of civilians caught in conflict. Her collected journalism presented posthumously in this volume runs from 1987 – the Iran-Iraq war, where she reported from both Tehran and Basra (“the day belongs to Iraq, the night to Iran” is one phrase she learned during this time) – and from there twenty-five years of on the ground reporting from the Balkans, Africa, America and, most extensively, throughout the Middle East.

Colvin is not the story here, although an Introduction by her sister paints a portrait of an astonishing, warm person with a gift for storytelling. She is however present in the writing in two ways – first her anecdotes, interactions with those caught up in modernity’s tumult, from the Rafah tunnel-diggers to Zimbabwean schoolteachers targeted by Zanu-PF, show her connectedness to others, as humanity seeps through almost grudgingly, against the staid, passive-voiced tone of The Sunday Times style-guideline paragraphs. In her writing she is fascinated by people, their personal place in the flotsam of politics.

The second way in which Colvin’s personality comes through is in her commitment. Commitment may be a better word than bravery – as she said herself, ‘bravado’ is posturing, about oneself, bravery about not being afraid to be afraid, to bear witness to a situation. The lengths to which she went to bear witness are brave, significant, because they produced this extensive body of work, an on the ground account of 25 years of conflict.

She was one of three foreign journalists to stay in East Timor after hundreds of colleagues withdrew in response to warnings that their lives were at risk; her decision to stay and her reporting contributed to the reversal of the UN’s decision to pull out. In Chechnya in 1999-2000, as Russian paratroopers cut off her last line of retreat, she fled with Chechen help over a 12,000 foot mountain range.

When she lost an eye from being shot in Sri Lanka in 2001, and received criticism for her decision to put herself in harm’s way, she replied that Sri Lanka was a forgotten conflict where some 60,000 had died since the start of the civil war, “a loss barely noticed except by their families.” Her own, personal response to this violence and the loss of one eye, at least as she documents it in her writing, is good-humoured: “on a week’s recuperative holiday on the Ligurian coast, I was told by Italian men that the patch was very sexy. Back in London […] children ask me why I am dressed as a pirate, which is delightful.”

In a rare passage where she focuses on her own work and life, speaking of the difference in treatment between her and her male colleagues, she notes that her male colleagues often gained greater praise for chasing the ‘Big Picture’ stories, which interested her less than human relations. Her profiles are vivid, written portraits: she spent a year profiling Yasser Arafat for a documentary (“his obsessive precision can be maddening”), and writes a heart-wrenching, cognitively twisting tale of identity, self and brutality in a profile of Latf Yahia, the man forced to undergo plastic surgery to work as the ‘double’ of Uday Hussein, Sadam’s infamous, seemingly sociopathic son – the attempt to transition back to his ‘Latf self’ after he has ‘served his purpose’ aches with the minutiae of individual psychological terrors under authoritarianism. The man who assassinated Yitzah Rabin is similarly conjured in her prose in all his itchy, discontented contradictions.

Wary as she was of the ‘Big Picture’ stories, her ability to untangle the most knotted of conflicts in her writing was much admired. Her reports from the Balkans, particularly Kosovo in 1999-2000, sift through the contested claims better than many full-length books on the region; her account from the killing field at the village of Meja in southwestern Kosovo is disquieting, while in her account of Djakovica, war and post-war sit together grimly both in the cobbled stoned architecture she draws out and in the profile of a bitter man who, before the war, was a ‘nobody’, until a shift of power meant he had muscle to decide whether his neighbours lived or died at the hands of Serb paramilitaries.

Her reports from Zimbabwe and Sierra Leone are harrowing, evocative: girls raped because they are seen as ‘symbols’ of an ideology in the eyes of Zanu-PF, the drug-fuelled, disillusioned ‘West Side Boys’ militia who developed out of Sierra Leone’s Armed Forces Revolutionary Council.

But it was, above all, the Middle East that drew Colvin, the fractures of religion, ideology and power-plays that she drew out through individual stories, from the Iran-Iraq war to the ‘war on terror’ to the Arab awakening. She reported on Iraq in 2002, in those early post-9/11 days as the neo-cons readied for battle and Saddam refused to flinch, asking what motivated the Ba’athist dictator to engage in his ‘suicidal’ position of refusing to cooperate with weapons inspectors. She provided a rare investigation of Israel’s secret war with Iran – that in the desperate race to stop Iran from developing nuclear weapons, they had begun to covertly assassinate the country’s top scientists, and subtle descriptions of the daily dramas involved in the settler removals in the West Bank in 2005, in those late Sharon days.

Her reports from Iraq are a reminder of how the tone of the last decade has been overshadowed by this war, leaving every citizen with a tragic story and an unreal new reality – in the mid-2000s the bombings come daily, the horrors unceasing. Colvin wrote a chilling depiction of al-Zarqawi’s notorious rise to prominence after 200 Shi’ite worshippers were killed by suicide bombers in 2004. She documented the pains of the post-Saddam purging of Ba’athists, the chasm between transitional justice principles and the reality of resentments and revenge-tales.

Her position on the fraught entanglements of Middle Eastern politics was complex, and lacquered by the passive-voiced tone of her The Sunday Times writing. She was criticised in establishment circles for being overtly pro-Palestinian, although reading her reportage as whole now it reads more like a basic recognition of the asymmetry of the conflict. Conversely, she received criticism for her report from Jenin in 2002, where she did not use the definite word ‘massacre’ to enclose the horrors of mass civilian deaths she witnessed (the claim of 500 civilians killed was firmly denied by Israeli sources, and Colvin’s reporting for an establishment mainstream outlet such as The Sunday Times and also refusing to name Jenin a ‘massacre’ could well be read, in retrospect, as a deferral to the ‘official Israeli account’ and a kind of whitewashing).

Similarly, much of her coverage of Iraq in the 2000s uses the language of ‘terrorism’ more than the language of ‘occupation’ – in other words, in the lenses through which she framed the post-9/11 world it could be argued that her writing replicated the worldview of states more than she conveyed the realities of people. This emphasis in her language would not entirely hold up to Gellhorn’s edict, which she herself quotes: to “never believe governments, not any of them, not a word they say, keep an untrusting eye on all they do.” But it feels, instead, more that she was working sneakily to smuggle the reality in through the confines of her establishment-voiced journalism; the Colvin her friends describe – warm, witty, razor-sharp– comes through almost against herself, a core the newsprint can’t repress.

Her precision brought out the internal divisions ‘within’ entrenched conflicts. Colvin was openly critical in her representation of Hamas as an extremist organisation capitalising upon the Palestinians trapped in Gaza. She traced the disentanglements of Afghanistan’s seemingly perpetual transition from its various occupations through her accounts of the struggles, and corruption, of the police force. Her writing on the Israeli bombing of Gaza in 2008-2009 included the heart-crippling story that could come from an Emile Habibi novel were it not pungently real – the doctor in Al Shifa hospital in Gaza City who faces the horror of seeing his own son brought in to the ward, a victim of the merciless Israeli bombardment.

Her reports from Iraq in 2010 show the swollen normalisation of fear that years of war delivered to the country – seven years after the American-led invasion, she describes Fallujah as the site of al-Qaeda’s new recruitment tactics. Similarly, her 2010 reports from Afghanistan stitch a narrative of ‘revenge of the Taliban’, while the 2009 Green Revolution in Iran disintegrates pitifully in the face of consolidated forces. In Egypt in 2011, Colvin briefly became the story as she was attacked; again in November 2011 she describes the mood in Egypt’s divided ‘second revolution’ as being much darker, with brutal police crackdowns jeopardising the elections and suspicious glances in the square of revolutionary elation – “I was caught up in a tidal wave of young men running from tear gas and shotgun pellets.” Her reports from Libya in 2011 conjure the psychosis of Gadaffi’s dying days – from Misrata she reported on how Gadaffi’s forces were accused of raping at least 1,000 women trapped by fighting in the front-line city; after the dictator finally falls, her writing slackens in a pause to reflect on her twenty-five years of knowing the Libyan ruler.

Her continually crisp prose and glistening details notwithstanding, the events do hurtle past, speeding up in the face of the mushrooming Arab Spring – the Israeli assault on Lebanon 2006, Hamas election in Gaza 2007, Gaza airstrikes 2008-2009, 2009 Iranian Green Revolution, 2010 Iraqi elections, 2011 Egypt, 2011 Libya, and then – you hold your breath knowing the last pages, her last reports – 2012: Syria. Homs. Her last articles were blistering with the quagmire of what had by then developed into civil war. Her friend Jon Swain writes an account of her last days in Syria, and her last days – Marie changed her plans to stay on for one more day to file an account of what she witnessed in Baba Amr.

Her death made headlines where others did not, an undeniable fact of a media structure that privileges the lives of some over others. But holding her 25 years of reportage in two hands, in the hefty, almost-overflowing form of ‘On The Front Line’, this headline-making end seems a kind of mirror to the task she lived and died for – her death was headline news because in her life she worked – tirelessly, intelligently, imperfectly, and generously – to tell the stories of those who history bulldozes and bludgeons in pursuit of its ‘Big Picture’ stories.

Her death made headlines where others did not, an undeniable fact of a media structure that privileges the lives of some over others. But holding her 25 years of reportage in two hands, in the hefty, almost-overflowing form of ‘On The Front Line’, this headline-making end seems a kind of mirror to the task she lived and died for – her death was headline news because in her life she worked – tirelessly, intelligently, imperfectly, and generously – to tell the stories of those who history bulldozes and bludgeons in pursuit of its ‘Big Picture’ stories.

On The Front Line

The Collected Journalism of Marie Colvin

Marie Colvin

Paperback: 560 pages

Publisher: HarperPress (26 April 2012)

[…] bedside, his face showing the exhaustion of almost two weeks of back-toback operations. – Extract from ‘On the Front […]