Review – Le Grand Voyage

Arts & Culture - Posted on Thursday, May 29, 2008 16:03 - 1 Comment

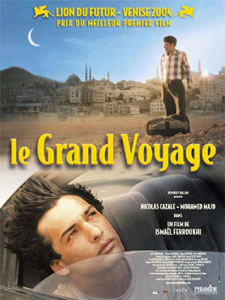

Review – Le Grand Voyage (2004)

Written and directed by Ismaël Ferroukhi

Tarik Oumezzane

Against his wishes, Reda (Nicolas Cazale), a young French man, is forced to drive his Moroccan father from the south of France to make the ‘hajj’, the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca.

Reda’s strong sense of filial obligation induces him to put both his schooling and girlfriend on hold. The wide cultural and generational gap between the two is worsened by their lack of communication. Reda finds it hard to accommodate his father, who demands respect for himself and his pilgrimage. This uneasy pair embarks on one of those journeys mean to lift the heart and stir the soul. Along the way the two cross national borders, seas, even continents, but no distance is greater than the one they cross to come to terms with each other. The two embark on a road trip that will change their lives.

During their journey they experience the cold snow mountains of Belgrade, and the hot dry desert of Syria and Jordan. They stay in reasonable hotels but also sleep many nights in their rather battered car. They have reasonable meals in cafés, but also have to survive on boiled eggs and bread for a quite a long period of their journey. A silent old woman dressed in black joins them and become a symbol of some unstated fear. Her face is expressive not only of sadness but of some tremendous nameless tragedy.

The director of the film allows space and time for us to interpret her presence; and with the sight of women wending their way out a distant cemetery the horrors of the Srebrenica massacre are reflected in the old woman’s expression. The journey takes father and son to the city of 1000 thousands mosques: Istanbul. Reda, in his interest to know more of the city, becomes more perceptive; and his desire linger gives him an opportunity to quote back at his father telling him “not to hurry: those who hurried are dead.” Despite believing that their money had been stolen, the father insisted on continuing their journey across Damascus and Amman. The conflict between father and son increases as the father slaps Reda across the face when he took back a charity that the father gave to a beggar and her child thinking that her need was the greater. The discovery of money sets up another dichotomy between the father and son; and while Reda chooses to go night-clubbing, drinking alcohol and associating with a belly-dancer, scenes of the father reading Koran, and praying, are interspersed. The outcome leads to a conflict in which Reda asked his father for forgiveness declaring that surely the father’s religion supports forgiveness.

On reaching Saudi Arabia, the true feeling of hajj becomes apparent in the support given to the father and son by other Hajjis. Reda shows his lingering passion for his girlfriend, Lisa by writing her name in the sand as the other Hajjis pray. A turning point in the film comes when father and son become closer and sit side by side in the desert alongside their car expressing how much they have learnt from their journey. At last they reach Mecca and the father begins his pilgrimage reciting “Labayke allohoma ma labiaka” – “I have come following your call”. That night Reda waits without any sign of his father. He starts looking for his father in sea of people all dressed alike for Ihram, with a rare glimpse of thousands- perhaps millions- of white-robed Muslims descending on the immense mosque. becomes frantic in the press of Hajjis and is restrained and removed by security guards. He finds himself in the ablution place of the mosque where dead bodies lie on a simple rugs covered in while cloth. The silence contrasting with the noise of the pilgrimage outside suggests the sacred nature of the place. The faces of the dead are revealed one by one to Reda by the Imam. His heart cries out when his father is uncovered. Very powerful scenes follow as Rada washes his father’s body. The dead and the living are close. The decisive action of Reda in the final scene to give charity to a beggar sums up the impact of the journey on the young man. Initially exasperated, Reda gradually learns to appreciate his father’s steadfast faith.

Framed by the clod snowy landscapes of the Balkan and the hot dry deserts of the Middle East, the film succeeds in combining many dichotomies: West/Islam; North/South; the have/the have-nots; religion/secularism: the old/the young; first generation Muslim in Europe/the second generation Muslim in Europe; materialism/Charity … all woven into a metaphorical tale of character transformation. Both father and son have learned lessons in faith and love, and discover that neither quality is what it may seem to be. The son begins his journey resentful and rebellious. The father is stern, inflexible, and tunnel-versioned. And both as they near their destination learn great truths about each other. Mecca, a city that seems far away, becomes, through Le Grand Voyage, accessible by car and by the human spirit, bringing with it the possibility that a journey to that city would be a process of self-discovery that we can all undertake. Only by affording each other basic human respect can we come to mutual understanding.

March 2006

1 Comment

OhCanada29

I find it always fun to fall on a Good blog that has actual good content! The last blog i read didnt have as much info as this one. Thx