Ireland: a political shift for the better? Special Report

New in Ceasefire, Special Reports - Posted on Sunday, June 3, 2012 21:19 - 1 Comment

By Lily Murphy

“The correlation between an area’s wealth and its support for the fiscal treaty couldn’t be starker”

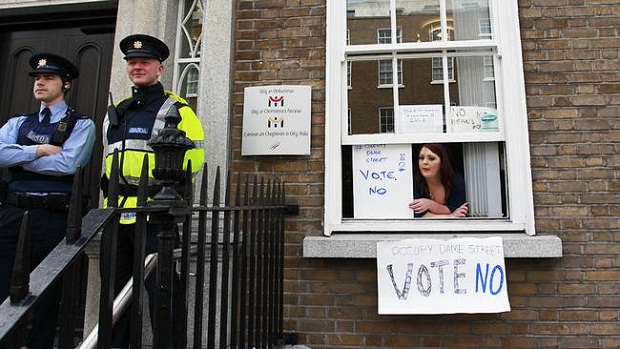

If the Irish fiscal treaty referendum showed us anything, it is that Ireland is falling into class politics. The referendum, which took place on Thursday 31st May, brought two clashing sides together: the ‘no’ side, which wanted to reject the fiscal treaty, and the ‘yes’ side, which wanted to accept it.

The yes side won, spearheaded by the conservative-led government of Fine Gael and the once left wing Labour party. The one time dominant, but now mired in corruption, party of Fianna Fail also fell into the yes camp. Those on the ‘no’ side consisted of Sinn Fein, now the most popular opposition party in the republic, the Socialist party, and the ‘People before profit’ party. Also behind the ‘no’ vote were several independent members of parliament, including well-known economist Shane Ross.

When polling day came, on Thursday May 31st, not many people bothered to go out and vote, resulting in one of the lowest turnouts in referenda history. Those who did vote cast a new light on an Irish political landscape that had, in a matter of just a few years, changed dramatically. The breakdown has been rather straightforward: voters in rural and middle class suburban areas voted yes while inner city and working class areas voted no.

The general election of 2011 heralded a new style of politics in Ireland. Out went the civil war politics which our parents and grandparents had been so much accustomed to, the one where you were either a Fianna Fail voter or Fine Gael, where no other choice dared to rear its head. 2011 marked an end to that as a new generation of voters gave their preference to new parties along with a string of radical independents.

The outcome of the fiscal treaty referendum cemented the shift in Irish politics. Ireland had never witnessed an industrial revolution and thus had no taste of class division, class warfare or even class politics. James Connolly and Jim Larkin brought the inequality of the poverty-stricken Irish to the fore at the turn of the 20th century but when Connolly was executed by the British authorities for his role in the failed Easter rising of 1916, class consciousness died with him.

After independence, Ireland fell into the clutches of the catholic church and only two parties dominated the political landscape. Equality came in the form of poverty which the majority of Irish homes knew all too well. Now, in 2012, we face the reality of Ireland as a country of the haves and the have nots. Poorer areas get poorer, more affluent areas prospered, with the chasm in between widening every day.

Class politics has been the norm for most of Europe but Ireland bucked that trend, until now. To paint a picture of this social and political shift, the highest yes vote percentage recorded in the country was at the constituency of Dublin south, an (in) famously affluent part of the country, where 75% of voters favoured the treaty. The highest no vote came from Donegal north east, where 55% of the electorate voted against the treaty. Donegal is a forgotten part of Ireland where emigration among the youth is rife and swathes are socially disadvantaged.

The correlation between an area’s wealth and its support for the fiscal treaty couldn’t be starker: voting yes was Dun Laoghaire, in county Dublin, another notoriously well-off area. The no vote was prevalent in Dublin north west, an inner city not so well off area.

In my own city of Cork the class division brought forth an even clearer picture. In Cork south central (my own constituency) the yes vote trumped the no vote by 62% to 48%, (I was one of the 48%) while in Cork north central the yes vote just about scraped by 52% to 48%.

Looking at these areas, elected representatives from Cork north central come from Sinn Fein, the Socialist party, The workers party, Fine Gael and the Labour party while in Cork south central elected representatives from there are predominately Fianna Fail, Labour and Fine Gael with some Sinn Fein. Cork north has always been much more disadvantaged compared to Cork south but that gap is widening even more both socially and politically.

Such a divide in Irish politics was going to happen at some stage in history and we are, I presume, witnessing it right now. The reason for such a shift may lie in the fact that the conservative Irish catholic church is all but dead and no longer enjoys the close relationship with the state it once took for granted.

The other reason is that Fianna Fail, like the catholic church, is also near death’s door. Two massive institutions that held social and political power over the Republic of Ireland for many generations have been dumped by a new generation far more educated and aware of the abuses of power. A generation, moreover, that is experiencing a financial recession brought upon it by years of political and social corruption.

Those who voted no to the fiscal treaty are those who have been worse hit by austerity measures. Once upon a time people in Ireland voted the way their parents did or voted how their parents told them to. They voted along familial allegiances to those in the past who were on the anti or pro treaty side of the 1922 civil war.

In modern Ireland, people seem more willing to vote the way their head tells them to, and not their parents. This also means they are voting Left or Right according to their social and economic status, with be no centre ground coalescing in this new political reality. The Haves go right, the Havenots go left. In between, drifting into irrelevance, we can see the ghosts of old style Irish politics, drifting towards the horizon.

1 Comment

Damien Smyth

There are some interesting works coming out of the History Department at Cork Uni. (UCC), including Donal O’Drisceoil’s ‘Peadar O’Donnell’ and ‘Politics and Irish Working Class, 1830-1945’ ed. Fintan Lane and Donal O’Drisceoil. Incidentally, Fintan Lane was on the Irish boat Saoirse which attempted to break the siege of Gaza late last year.

Also, on Dublin Community TV – http://www.dctv.ie/main/ – there are a series of five lectures on radical social movements in Irish history under the title ‘5 Wednesdays’ (ie. five wednesdays in May). They’re organised by academics involved in the Occupy movement and, along with the Q&A sessions at the end of each, are very interesting.