The Hunger Games: Riding Roughshod over Human Rights and Human Dignity Comment

New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Thursday, January 2, 2014 13:19 - 1 Comment

By Aisha Maniar

Hunger strikes featured prominently in the work of the London Guantánamo Campaign in 2013. The ongoing Guantánamo hunger strike started on 6 February 2013 and we organised the first solidarity demonstration anywhere. Getting several dozen people to stand outside the US Embassy in the pouring rain on St Patrick’s Day was no easy feat for a grassroots organisation, especially when six weeks into the hunger strike, the issue had not been mentioned in the mainstream media at all.

By the time the media caught up, we were well on our way to organising a weekend of actions in May to mark the hundredth day of the hunger strike. For prisoners held like hostages, mostly without charge or trial for over eleven years, this non-violent protest was an ultimate act of desperation.

Their desperation was mocked, and the mass hunger strike was quelled through repressive measures, including solitary confinement, force feeding through nasal tube, physical examinations tantamount to rape, and other measures designed to break the will of the hunger strikers. The United Nations described the force feeding as “torture”.

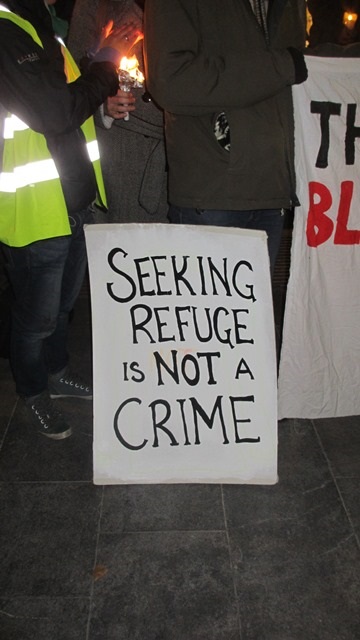

As a small organisation, we also held a number of solidarity actions throughout the year with hunger-striking prisoners elsewhere. It did not fail to catch my attention that simultaneously prisoners held at immigration removal centres (IRC) in the UK, sometimes for years without charge or trial on the non-existent offence of having a foreign passport, were also undertaking lengthy and potentially fatal hunger strikes in a bid for freedom.

Outside the United States, the force feeding of prisoners is a false debate; the issue has long been settled as illegal and a contravention of international medical ethics, if a person has mental capacity. As a result, rather than allow hunger-striking detainees to die, in June, Harmondsworth IRC released four prisoners – an Algerian and three Nigerians – who were facing deportation and had been on hunger strike for over seven weeks. One man was reported to be close to death. A total of 17 detainees at the facility went on hunger strike; others are reported to have been moved to other facilities.

By the time another Harmondsworth hunger striker Samuel Sorinwa was released on bail in early August after a High Court ruled he should be released to hospital amid warnings he was close to death, overriding a Home Office assessment, an immigration detainee charity said that the decision to release hunger striking prisoners was being taken at ministerial level, and not by judges. This signalled a hardening stance by the British authorities.

It is perhaps no mistake that in a previous incarnation, Guantánamo Bay served as an immigration detention centre for Haitians trying to enter the US. Britain’s immigration removal centres are one facet of Britain’s own Guantánamo-style regime: the regime of abuse and impunity that function within them, and the excessively long periods for which some people are held without charge or trial, are just two similarities.

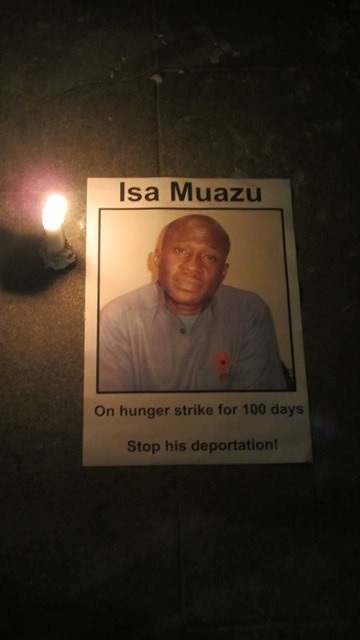

Military might tried but failed to end the hunger strike at Guantánamo Bay, which is growing once more. In Britain, the Home Office’s position reached its logical conclusion in the case of 45-year old Nigerian Isa Muazu, and Home Secretary’s Theresa May’s desperate but ultimately successful attempts to deport him.

Having overstayed on the visitor visa he used to enter the UK in 2007, Isa Muazu applied for asylum in July 2013, claiming possible persecution by the militia group Boko Haram if returned to Nigeria; this was rejected. Held in immigration detention since, his deportation was fast-tracked and he started a hunger strike in late August, refusing food for the most part and water at times, as well as medical assistance. After almost one hundred days, considerably ill and weakened, his hunger strike ended with his return back to the UK, when the £180,000 charter flight commissioned especially to return him to Nigeria was not given permission to land there.

In sending Muazu to Nigeria, potentially to avoid responsibility for his death, on board a second charter flight, with others facing deportation on 17 December, the Home Secretary simply showed herself to be ruthless. There were no political points to be scored. As with the Guantánamo hunger strike, it is Britain’s reputation that is damaged, demonstrating that governments will act in this manner simply because they can.

Accusing hunger strikers of not being genuine and “attention seekers” is cheap; the real issue relates to how we as a society treat our most vulnerable members, who in many cases, in the case of asylum seekers, are in that vulnerable position as a result of our foreign policy. Human life and human dignity are not pawns or commodities to be played or bartered in power games. The trickle-down effect cannot be ignored either, as the US government introduces Guantánamo-style provisions into its domestic laws, and the Home Secretary continues to assign herself arbitrary powers.

The actions of governments, however, do not reflect those of the people; solidarity has not been lacking. The British response to the Guantánamo hunger strike has been tremendous, with solidarity hunger strikes and over a dozen actions held across the country as part of our weekend of action in May. Likewise, protesters physically attempted to block the first attempt to deport Isa Muazu on 29 November, and there was high-profile support all round, and lawyers, in both the US and the UK, have worked hard to protect their clients’ rights.

Near-fatalities, brute force, and blatant human rights violations will not stop those in power from acting in a manner that is undemocratic and non-transparent in the name of democracy. Society, which pays for these repressive measures with or without its consent or awareness, thus has the challenge of continuing to show solidarity and standing up for those for whom the only means of protest and negotiation left is their own bodies and lives, or losing more than was bargained for.

1 Comment

Walter Benjamin: Critique of the State (and resistance) | ΕΝΙΑΙΟ ΜΕΤΩΠΟ ΠΑΙΔΕΙΑΣ

[…] Comment | The Hunger Games: Riding Roughshod over Human Rights and Human Dignity Thursday, January 2, 2014 13:19 – 0 Comments […]