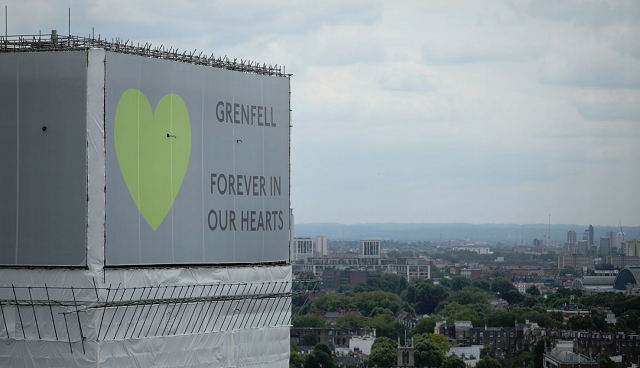

Grenfell and the Ghosts of History Analysis

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, June 14, 2019 16:58 - 1 Comment

By Mark Olden

The threat of insurrection in North Kensington was real in the days after Grenfell.

How, people asked, could those who ignored residents’ complaints before the fire, who signed off on the cladding which — as was immediately clear — helped it to spread so fatally, and who were nowhere to be seen in the immediate aftermath, have legitimacy in the neighbourhood?

Within days, the rupture between locals and the authorities led activists to declare this corner of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea a ‘people’s republic’, and the streets around the charred tower an ‘autonomous zone’.

As the months passed, calls for self-rule faded. There were signs though, that the advance of ‘super-gentrification’ in the borough, with London’s greatest extremes of income inequality, was being checked.

Locals took over empty buildings. They covered public spaces in painted hearts and makeshift memorials; they set up art therapy, gardening and childcare projects. The Tory-led council was forced to abandon its plan of leasing the local library to a £19,000-a-year private prep school, and to apologise for its role in the intended sale of a further education college. A new affordable housing policy was proposed to prevent Kensington “becoming a borough only for the rich”.

But today, as we commemorate the second anniversary of one of Britain’s worst peacetime disasters since World War Two, normal service, it appears, has been resumed.

The authorities — so vulnerable in Grenfell’s wake — have reasserted themselves. At the same time, the Public Inquiry into the fire is mired in delay, with the judge leading it yet to make a single recommendation on fire safety — despite his experts warning that “urgent and very far-reaching reform” is needed. What’s more, no charges are expected in the ongoing criminal investigation before 2021.

All of which leaves survivors, in the words of a recent report by Inquest, feeling “abandoned by the state at all levels”.

Yet it is the survivors and bereaved who are creating the disaster’s most tangible legacies. And in their quest for justice, they’re mirroring the response to earlier traumas in the same area.

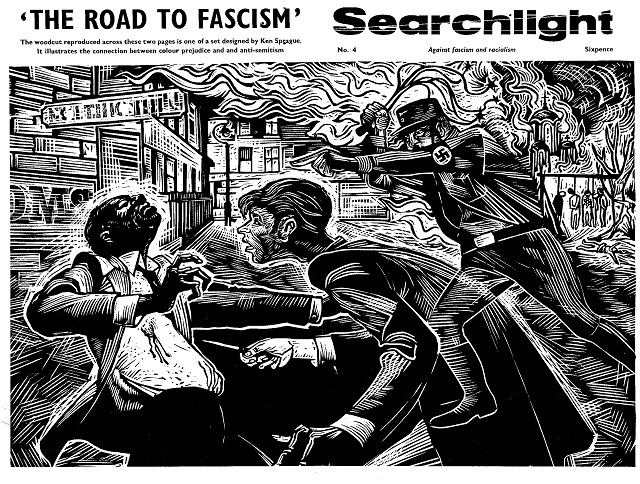

A knife-wielding Teddy Boy is urged on by a Nazi. Political cartoonist Ken Sprague’s take on Kelso Cochrane’s murder.

Haunted by things that no longer exist

Tom Vague, North Kensington’s unofficial historian and a walking repository of tales from Notting Hill in bygone days, often speaks of the district’s ‘psychogeography’: how its terrain, and the things that happened there in the past, somehow vibrate their influence in the neighbourhood into the present.

Walking the streets of North Kensington, where I’ve lived more than half my life, there are times when I think this is nothing more than perception. As recently as the mid-19th century, much of the area was farmland. In 200 years, the streets and buildings might be equally unrecognisable: they’re impermanent, like the lives which pass through them.

There are other times though, when I can feel — or at least imagine — the presence of those who came before; when Notting Hill’s history seems to seep through its architecture and landscape, like the barely visible traces of the decades-old painted advert on the wall by Ladbroke Grove tube station.

The 14th day of every month is one of those moments: when thousands walk silently up Ladbroke Grove, forcing traffic on the busy main artery to a halt, their banners demanding justice for Grenfell’s 72 dead.

Among them are at least a handful who are aware of the procession that headed silently north up the same road 60 years ago.

Back then, the crowd, stretching back half a mile and numbering around 1,000 people, was made up of black and white, young and old, and was also seeking justice and catharsis: for the unprovoked murder of a black man in the area three weeks before.

At around midnight on May 17, 1959, Kelso Cochrane, a quiet 32-year-old carpenter from Antigua, was attacked by a gang of white youths on the corner of Southam Street, in the derelict northern fringes of the borough. One of the assailants drove a knife deep into the main chamber of his heart.

Kelso’s murder came eight months after the Notting Hill riots, among the worst outbreaks of racial violence in Britain in the last century. The murder of a black man in the same district threatened greater disturbances, and its news reverberated around the world. “The savage murder was premeditated. There is no rest on London these days,” said Radio Moscow.

Despite the killer’s identity being the “worst kept secret in Notting Hill”, no one was ever charged for the crime. For many, this was a brutal symbol of the different values the law placed on black and white lives.

Yet rather than triggering more violence, Kelso Cochrane’s murder brought people together. “His death,” says the blue plaque just across the road from where he was ambushed, “outraged and unified the community, leading to the lasting cosmopolitan tradition in North Kensington.”

“Something stirred in people,” says the local sociologist and documentary film-maker, Colin Prescod. “If you look at the pictures of Kelso’s funeral, you see a community which is shamed by this racist murder. After his death there was a resistance: where people were trying to change the social and political culture in which they lived.”

Prescod arrived in North Kensington from Trinidad as a 13-year-old, just before the August 1958 riots. His mother, Pearl, who became the first black actress to appear at the new National Theatre at the Old Vic, was at the vanguard of creating the political and social change he speaks of; along with the likes of Amy Ashwood Garvey (the ex-wife of the Pan-Africanist leader Marcus Garvey), and Claudia Jones, the Trinidadian-born communist who was jailed in America, and then deported, during the McCarthy witch-hunts.

Out of the embers of the riots and Kelso’s murder, they and others created a form of ‘social healing’: in concrete terms, this included starting the forerunner to the Notting Hill carnival (today a global symbol of multi-culturalism), and transforming North Kensington from an area synonymous with racial hatred into one which for decades was seen as a cultural melting pot, where different races and classes cohabited in ways unfamiliar in other parts of London.

There was also national change: Jones and others used the violence in Notting Hill sixty years ago to help force anti-racism on to the mainstream political agenda, which eventually led to the UK’s first Race Relations Act in 1965.

History of resistance

The parallels between the death of one man in North Kensington 60 years ago, and those of 72 people there in totally different circumstances in June 2017 should not be overstretched – despite both events exposing stark truths about the Britain of their day. The comparison, rather, is how people responded to what happened, and the change which flowed from it.

In the case of Grenfell, it’s the survivors and bereaved in particular, who are leading the change.

Grenfell United was formed by homeless and deeply traumatised survivors soon after the fire. The group now includes most of those who survived the tragedy, as well as hundreds of bereaved relatives.

At first they fought for medical support and accommodation. Since then, they’ve battled for “justice and accountability and to honour the memory of those who died”. They’ve won significant victories – though not the war – in their campaign to ensure that no-one else in the country lives or works in high-rise death traps; they also recently won their fight for the Grenfell inquiry to have a more representative panel. More broadly, they are also working to end the prejudice against social housing tenants.

Yet in North Kensington itself, Grenfell’s lasting impact remains unclear.

The vast concentration of grief among so many remains, as does the question which was asked in the area as the horror unfolded two years ago: how can those who failed residents so catastrophically still be part of the structures that govern their lives?

Text is excellent. I hadn’t read anything both significant and objective in a long time. This is a fantastic script for newcomers. I’ll recommend it to my friends who are stumped as to where to go.