The BBC cannot fight ‘fake news’ if it’s part of the problem Analysis

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Tuesday, November 26, 2019 17:43 - 1 Comment

By Paul Bernal

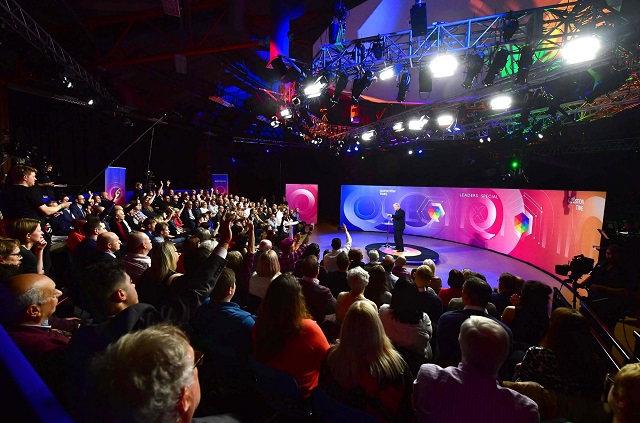

“The BBC produced an edited clip of Boris Johnson’s response to a question about honesty in politics.”

Over the past week, the BBC has managed to get itself into a real mess over its Question Time Leader’s Debate on Friday — a mess that not only demonstrates a number of aspects of the current ‘fake news’ and misinformation debate, but highlights the challenges facing the ‘mainstream’ media in these troubled times.

The ‘traditional’ and ‘respectable’ media, of which the BBC is perhaps the most important standard-bearer, could and should be critical to addressing the fake news problem but in practice often ends up fuelling it. Whether it does so deliberately, negligently or just accidentally is sometimes hard to tell — but the failure, particularly from the BBC, to understand or at least acknowledge their role, let alone begin to address it, is potentially disastrous for our political future. This is something that many of us who grew up with the BBC, respect the BBC and in some ways actually love the BBC, find desperately sad.

Fake News and ‘real’ news…

‘Fake news’ is not a new phenomenon — it is something that has existed throughout human history. Examples can be found from every period. Those who wish to spread it use whatever is the best and most appropriate medium available at the time. From the woodcut-printed pamphlets used to blacken the name of Vlad the Impaler (who was not quite the villain he is commonly believed to be) and songs sung in the street in 17th Century France to the newspapers of 18th Century Germany and the radio broadcasts of Lord Haw Haw and Hanoi Hannah in the 20th, as technology advances so does fake news. Now, in the internet era, that means social media: Facebook, YouTube and Twitter in particular. The way that social media works, the ability to create, broadcast, target and virally spread information in moments, and the complex relationship between the ‘traditional’ and social media, is what makes the fake news phenomenon of the current era qualitatively different — and significantly more dangerous — than in the past.

Fake news has always had a difficult relationship with ‘real’ news. Powerful people have always had a tight grip on ‘official’ sources of information and have tended to use them to spread the kind of ‘news’ that suits them. This grip does not have to be direct, and is often through the creation of an atmosphere and an ‘understanding’ according to which if a broadcaster or newspaper steps out of line, or rocks the boat too much, then there will be consequences. A culture of compliance means self-censorship happens — but it also means that journalists can avoid looking sufficiently critically at the information fed to them by those in authority and, in so doing, end up actively spreading the kind of misinformation that the authorities want to spread. This is one of the ways in which the BBC has been seen to be working — the failure to call Boris Johnson, in particular, to account, and the way in which ‘Number 10 Sources’ have been able, and allowed, to put their messages out to the public.

Fake news and fake narratives

The most important thing to understand about fake news is that the news itself is not really the point. The details barely matter — and neither does the fact of whether the news items themselves are individually true or not. What matters is whether the ‘news’ feeds the narrative that the misinformer wants to spread. Indeed, if they can find ‘real’ news to feed the fake narrative, that’s even better than using something completely fake. Taking ‘real’ news out of context, spinning one particular aspect and downplaying another, subtly altering some particular fact so that the ‘real’ news fits the fake narrative — these are all tools used regularly.

That, in effect, is what the BBC were accused of in this example. The BBC produced an edited clip of Boris Johnson’s response to a question about honesty in politics. In the original debate, both the question and Johnson’s hesitant response provoked what can only be described as mocking laughter. In the edited version, the laughter was missing, as was the hesitation; and the reaction to Johnson, rather than being in most ways derisive, ended up looking as though the audience was supportive or even approving. This is another way in which the mainstream media helps fuel fake news: through the editing of the truth to change its meaning — and, most importantly, to change the narrative.

The ‘desired’ narrative is that Boris Johnson is calm, competent, decisive and popular. The unedited footage shows him to be hesitant, incompetent and unpopular, but by using a relatively simple edit, the narrative is shifted. Whether this was done deliberately — some kind of direct command from above, some kind of general instruction about editorial policy — is another matter. It might just as easily have been done accidentally — editing video to make it neat — or subconsciously, if the editor didn’t want to cause problems. It might even have been done to make the debate itself look more professional. Editing out the ‘ums and errs’ is pretty standard editing practice, and not just in news, and it’s a small shift from that to editing out laughter too. An overzealous editor might easily do that — and this appears to be the essence of the explanation that the BBC finally gave for the edit, some 48 hours after the event.

It might be a ‘reason’ it happened, but it really isn’t an excuse. The BBC should have known better. The critical faculties of those responsible for the news should at the very least have noticed that the impact of the edit was to be misleading. If they had been attempting to shift the narrative deliberately, this kind of edit would have been exactly what they would do. Indeed, it is exactly the kind of thing that those manipulating video do in practice: the notorious edit by the Tories of Keir Starmer’s interview to add hesitation when answering a key question, just a few short weeks ago, was following exactly these lines, though in the opposite direction. The BBC could and should be aware of this technique — one of a number of key methods of misinformation in the current era that they should understand, avoid using, and prepare better to prevent.

Clips, tweets and headlines

A related method that the BBC needs to understand is the way that social media allows — and in effect encourages — things to be taken out of context. If, for example, a journalist posts one tweet quoting a politician saying something they know is not true, but only reveal in their next tweet that the evidence says the politician’s quote is wrong, that first tweet is the one that will be RTed, quote-tweeted, screenshotted and used by the supporters of the politician. The context, the critique, the evidence that the politician was lying will be ignored and in effect lost. This is where the criticism that journalists have become mouthpieces for politicians comes into play — and something that the journalists could, and should, be better at dealing with. The criticism and context must be provided in the same tweet as the quote they refer to.

“There will be 40 new hospitals built, the minister revealed”

…compared with…

“There will be 40 new hospitals built, the minister told us, though evidence shows that only 6 will actually be built, and funding for those is not fully costed.”

There is a similar problem with headlines. It is critical to remember that very often headlines are all most viewers/readers get to see, as people don’t bother reading the articles beneath them, may not even see those articles as the headlines are all that appear in search results or in tweets. Journalists will often tell you that they don’t get to choose the headlines that go with their articles, and thus cannot be held responsible for them: In the social media era, that is not good enough — journalists and editors need to know that, and take much more care over them. Unconscious bias can come into play here very much, as it can in the choice of particular words in tweets and headlines. In the example above, saying the word ‘revealed’ suggests what the minister is saying is true, whilst using ‘told us’ is neutral. If there is significant doubt, the word claimed might be even better.

What can be done?

The first and most important thing that the BBC and other ‘respectable’ news organisations need to do is become a little more aware of all of this — and a little less high-handed in their response to criticism. There are problems, and they need to face up to them. The BBC in particular should be playing a key role in fighting against misinformation, providing ‘anchor points’ of real news against which the fake news and other misinformation is measured. They need to build trust — something that is distinctly lacking at the moment, and events like last week’s edited clip will do a great deal to damage.

The first and most important thing that the BBC and other ‘respectable’ news organisations need to do is become a little more aware of all of this — and a little less high-handed in their response to criticism. There are problems, and they need to face up to them. The BBC in particular should be playing a key role in fighting against misinformation, providing ‘anchor points’ of real news against which the fake news and other misinformation is measured. They need to build trust — something that is distinctly lacking at the moment, and events like last week’s edited clip will do a great deal to damage.

At the moment, the defensiveness, unapologetic nature and apparent arrogance in the BBC’s responses — first to the questions about what’s happened and then in the non-apologies when they acknowledge that something went wrong — not only breaks trust but feeds the conspiracy theories about the bias and lack of integrity in the BBC. Huw Edwards suggesting that Peter Oborne looked ‘crackers’ for wondering what was going on was an awful example — classical gaslighting really — that should never have happened. A long hard look in the mirror by a number of people in the BBC is pretty crucial right now.

This also hits at the essence of the problem: Honesty. If the BBC cannot even look at its own output with honesty, how can it possibly fight against misinformation from other sources? The whole affair, from the initial edit, through the denials and the gaslighting, to the eventual grudging admission, causes nothing but damage, not just to the BBC but to trust in information overall. That, it should never be forgotten, is the ultimate aim of those involved in misinformation: to create an atmosphere where nothing can be believed, where nothing can be trusted, where conspiracies are rife and one person’s misinformation is every bit as ‘valid’ as all others, where genuine experts get derided and ignored, and you end up with the kind of chaos that the worst of people can exploit. We are perilously close to that situation now.

1 Comment

Laureen

Brilliant article & the BBC must know by now what we think of them and their propaganda nonsense. Lots of us have put in complaints about the disinformation by the journalists on Twitter and the fact they completely ignored the big demo in London and all you get back is an acknowledgement then saying they’re so busy it might take awhile to get back to us. They cut wonder why about 125,000 people have cancelled their tv licenses. They have codes of practice & they’ve been breaking them for the last 59 weeks. They need to be outed along with all the other gutter press. We all know they are paid off by the government and Bill Gates has pumped about 23 million into them. They need exposing for the criminals they’ve become.