Review: Macbeth: Leila and Ben – A Bloody History ( LIFT) Theatre

Arts & Culture, New in Ceasefire, Theatre - Posted on Wednesday, August 1, 2012 19:31 - 0 Comments

By Sheyma Buali

“How many Macbeths do we have in the Arab world?”, the narrator asks in his poetic introduction, giving context to this new version of Macbeth about to have its world premiere.

Rewritten to fit the current Tunisian scenario, here we see the recently ousted Tunisian president Zine Al Abedine Ben Ali and his wife, Leila replacing the Scottish Macbeth and his Lady. Straddling the margins between the pathetic and the fierce, the parallels between reality and this Shakespearian work make it a fitting prism for a historical enquiry into the cycles of power and oppression that have dominated Tunisian (and greater Middle Eastern) history for decades.

The play had its world premiere as part of the World Shakespeare Festival’s collaboration with this year’s London International Festival of Theatre (LIFT) before moving on to Newcastle’s Northern Stage. Co-adapted by director Lotfi Achour and actors Anissa Daoud and Jawhar Basti (who also play the lead roles of Ben Ali and Leila respectively) and performed by the Tunisian company, Artistes Producteurs Associes (APA), this rendition of Shakespeare’s bloodiest play could not have been more relevant and bold. Its strongest affect is its piercing aesthetic of viciousness that informs its historical conception of Tunisian politics.

Macbeth: Leila and Ben Ali – A Bloody History in its use of drama, music and philosophy, was refreshingly daring. Taking an internationally recognized drama on tyranny and greed and turning it into something that fits today’s revolutionary climate, it asks pertinent questions: how, from where, and to whom is power bequeathed?

The original Shakespearian play tells the story of Macbeth who is advised by three witches that he is destined for power. Relaying this information to his wife, Lady Macbeth, she urges him to kill the current king. In their path to keep that power, they are haunted by their own guilt and mistrust.

Those familiar with the play come with an understanding of what they are about to see, a tale of greed, murder and paranoia, a history haunted by henchmen fighting tooth and nail to keep their power; a vivid image that the world has unfortunately now seen in so many different guises of men ascending to (and keeping) their thrones by force.

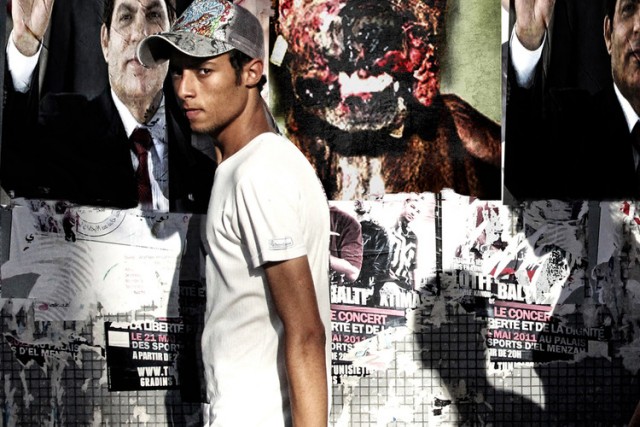

In APA’s version, we see the Tunisian presidential court: just like Lady Macbeth, Leila is the instigator behind her husband’s ruthlessness, appealing to his manhood as the source from which he should have the strength to seize control. Murder, blood, tyranny; the couple is isolated like rabid dogs fed by their own greed and paranoia, all part of the cannibalistic cycle of power eating itself alive.

Almost prophetically, APA began working on this play before the uprising. The project came about as a reaction of disgust to the fact that Ben Ali, as a revolutionary, and like the worst despots in the region including Saddam and Gaddafi, had led his people against their previous oppressor, Habib Bourguiba, only to ultimately maintain the oppression and put himself in the seat instead.

Now, more than a year after Mohammad Bouazizi set himself on fire and sparking a region-wide uprising, they are weary of seeing the cycle repeat itself yet again. Basic political liberties have surfaced, but a lot has remained the same. Director Lotfi Achour explained in the Q&A after the show how “The mafia, old economics and repressive system is the same. The removal of Ali and Leila hasn’t changed much.”

With the riots flaming across Tunisia last month in reaction to artworks that offended religious communities, anger rages on with concerns changing focus. While in some ways fear barriers have been broken and people are freer to express themselves, with conservatism as a dominating order creative expression is becoming a euphemism for impious behaviour. As threatened artists themselves, the soul in the drama and music came from the gut of the actors who were not only presenting a work of creative political expression, but also saying something about their ongoing struggle: Tunisia is still fighting, and nobody’s ideology should be enforced upon another.

The music, moving and raw, included a duet of particular malice. Like a dark regicidal Bonnie and Clyde, Ben Ali and Leila with their jet black hair slicked back rock out under a shiny chandelier to a horsey demonic tune celebrating their newly found power while images of bloody dogs are projected onto the background. At other times, grown men timidly sing forced praises for the new president, simply replacing the old with the new, keeping it open for the next.

Between scenes, interviews with philosophers run in snippets: Arabs were rich in poetic philosophy, but poor in political and social thought, one would say. Another brings up the pertinent point on citizenship, an idea that doesn’t yet carry the same credence in the Arab world, where people are treated as subjects.

A third speaker brings up the question of responsibility among a people who have become passive towards the powers that be. The thoughts were variant, at times contradictory, the aim was to open up to the multitudes of opinion, including those of activists, anarchists, Islamists and journalists, “because,” as Achour stated, “none of them had much opportunity to speak during Ben Ali.”

Until now, the play has been criticized for swaying from the original Macbeth. But such a critique is a reflection of a banality in critical engagement. APA’s reinterpretation serves a particular purpose: it was appropriated to make a voice, reinvented to illustrate a point and used as a tool to explore a history.

The play’s self-critical tone was not constricted to Tunisia or the Tunisian people, but rather challenged the overall culture of complacency in the region; an affective reinterpretation of a 400-year-old historical drama resonating with dire parallels to a political present in flux.

MACBETH: LEILA AND BEN – A BLOODY HISTORY

By William Shakespeare<

Adapted by lotfi Achour, Anissa Daoud and Jawhar Basti

An ARTISTES, PRODUCTEURS, ASSOCIES production

London International Festival Theatre (LIFT)

Leave a Reply