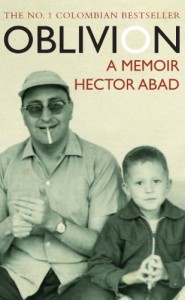

South of the Border “Oblivion: A Memoir” by Héctor Abad

New in Ceasefire - Posted on Saturday, February 26, 2011 0:00 - 0 Comments

By Tom Kavanagh

A tragic account of struggle and loss in Latin America, Tom Kavanagh reviews Hector Abad’s recently released memoir.

Composed as a tribute to his father, brutally murdered in the summer of 1987 during a period of intense violence in Medellín, Colombia, Oblivion charts the author’s life as the son of a philanthropic, socially conscious doctor and university professor considered a dangerous subversive by powerful elements of the country’s ruling class.

Abad Junior paints a picture of his father as something of a rare breed among Colombia’s medical intelligentsia in the latter half of the twentieth century: someone who was insistent on bringing the benefits of advanced science and medical development to the poorest sectors of a sharply stratified society.

For embarking on this crusade, which gained increasing public momentum and notoriety as his years advanced, Hector Abad Senior was vilified by many within the Colombian political establishment, and made a name for himself as a leftwing agitator and menace to the ‘natural’ order which saw the impoverished suffer in miserable conditions, dying from easily preventable diseases as a matter of routine while just a few blocks away rich families lived in opulent surroundings, buying cars and electronic goods imported from the United States and attending private schools and health clinics.

The author makes no secret of the fact that his family was well off. He tells of holidays and plane rides to Cartagena and overseas – a luxury far beyond the means of most in 1960s Colombia. His mother, who herself had grown up in a wealthy family, set up and ran a successful business, allowing her to support a large family while her husband’s modest university wage rarely stretched to affording the lifestyle to which she had become accustomed during her youth.

Abad Senior’s story is one of a man ashamed and disgusted by the conditions endured by most of the country’s people, with his medical background providing the catalyst for a concern with public health that was to underpin much of his political campaigning in later life.

While most doctors sought to enrich themselves by providing treatment exclusive to the affluent in expensive private hospitals, Abad would do the rounds in Medellín’s poorest barrios, taking whole classes of students with him to observe the effects of poor sanitation and malnutrition on public health in Colombia’s second largest city.

The doctor impressed upon those he taught the importance of preventing disease before it could form, taking great pains to highlight the fact that most of those suffering from poor health in precarious neighbourhoods did so because they lacked the financial resources to eat well and provide adequate sustenance for their children. He saw basic nutrition and access to clean running water as essential priorities for anyone concerned with public health – to the doctor, these factors were the most severe example of injustice in the society he found himself in, and a good deal of his time was spent raising awareness about these issues.

Despite being held in high esteem by his students and other prominent members of his faculty, Abad’s political leanings and his involvement in community activism made him a thorn in the side of the University of Antioquia’s leading lights, and he was eventually pushed out of his cherished position.

He went on to work with the World Health Organization, travelling the world and spending extended periods in Asia, with the author noting that these spells of paternal absence were particularly traumatic for a young man who was obsessed with his father in every way. From his role model he gained support and encouragement, declaring that had his father not praised his first attempts at ‘writing’ –incomprehensible scribbles to which the young boy dedicated much of his infancy – Oblivion may never have seen the light of day.

Abad Junior recounts a childhood in which he was forced to balance pressure from his mother’s side of the family to adopt Roman Catholic doctrine, compounded by undertaking his secondary education at a Catholic school for boys, and his father’s determined indifference to religious teaching.

Abad Senior, obsessed with philosophy and classical music, was of a steadfastly secular persuasion, and this gave his son a grounding through which to resist the imposition of Catholic teaching at a school he had only been allowed into after pressure was brought on the necessary powers by a well-connected uncle: his father was known as a troublemaker in the city and many of the more exclusive private schools in Medellín rejected the young boy’s application for this reason.

The professor’s position as one of the most consistent and outspoken defenders of human rights and advocates of elevating the position of the country’s poorest citizens earned him the “communist” tag in many circles, and would eventually catch up with him in the most brutal of fashions. In a city already enduring a wave of violence that killed many before and after Héctor Abad’s untimely but predictable murder, his funereal procession brought thousands to the streets in mourning for a man who had been one of the state of Antioquia’s most outspoken critics of government support for ruthless paramilitary groups which were shielded from prosecution as a matter of established policy.

The cycle of violence which claimed the doctor’s life would continue to grip Medellín for many years to come, earning the city a justified reputation as one of the planet’s most dangerous. Nowadays the likes of cocaine kingpin Pablo Escobar and other lords of the criminal underworld have nowhere near the power they once wielded, but the city is still gripped by immense inequality: from virtually any point the hills lined with ramshackle, makeshift houses are visible, providing shelter for hundreds of thousands of poor people whose lot has scarcely improved since Abad’s slaying over twenty years ago.

Oblivion is an intriguing book on many levels. Replete with anecdotes which offer an interesting insight into life in Medellín at the time, there is also a good deal which forces the reader to ponder on questions which transcend obvious cultural aspects unique to the Colombian context of the story. At times the book drags, and easily the most compelling passages are those dealing with Abad Senior’s involvement in trying to document and draw attention to atrocities carried out by third parties with the blessing of the Bogotá government along with the ongoing struggle for dignified conditions for the destitute masses.

The eventual murder of the book’s main protagonist is inevitable long before it is described in gruesome detail, and underscores the dangers of speaking out against oppression and injustice which continue to haunt many that refuse to toe the line in today’s Colombia, albeit despite massive improvements in the overall political situation and slowly diminishing impunity enjoyed by paramilitary entities.

Abad Senior is evidently revered by his son, who wished to leave something of the doctor’s legacy to the world in the hope that his death and the suffering this brought to many would not be entirely in vain. Oblivion achieves this, and the reader is left with the sense that the sacrifice the doctor made paved the way for some improvements in the country he lived in. Twenty three years on, however, the extent of social inequality in Colombia still leaves much to be desired, and it is mainly for this reason that Abad’s struggle still warrants exposure.

Tom Kavanagh, a writer and activist based in Argentina, is Latin America correspondent for Ceasefire. His column on Latin American affairs appears every Monday.

Oblivion: A Memoir [Hardcover]

Hector Abad Faciolince

Hardcover: 272 pages

Old Street Publishing (2 Nov 2010)

Leave a Reply