Mapping a metropolis Books

Books, New in Ceasefire, Photo Essays - Posted on Wednesday, June 22, 2011 14:57 - 0 Comments

By Andrew Fleming

London, as Simon Foxell’s excellent book makes clear, is a metropolis that has been endlessly and obsessively redrawn. The city’s historical weight and territorial range is great enough to sustain an almost endless spectrum of reinterpretations, ranging from the monolithic Ballardian flyovers of Iain Sinclair’s London Orbital to the labyrinthine warrens of subcultural detail found in Michael Moorcock’s Mother London or Alan Moore’s From Hell.

Indeed, thanks to writers such as these, an emphasis on the capital’s mysterious hidden reverse is in many ways as familiar a way of reading the city as Harry Beck’s iconic circuit diagram of the London Underground. The root of all this hermetic, intensely personal mapping can be traced back to Ralph Rumney and the activities of the London Psychogeographical Association in the 1970s.

By reinvigorating the disinterested urban flaneur of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century with a shot of avant-garde daring cribbed from the Lettrists and Guy Debord, Rumney and his cohorts staked that London could best be understood from the ground up, mapped from the hauntological resonances of its forgotten places and disregarded inhabitants.

Now available in paperback, Mapping London delineates the other side of this coin: the efforts made across the centuries to impose or wrestle order onto the city by depicting it pictorally from above. Cartography is always a political venture, and, as Mapping London makes clear, one that can have multiple and varied stakeholders.

Importantly, efforts to inscribe systematization in this way should not be exclusively understood as an authoritarian attempt to tame the city’s wild spirit. The most thrilling maps in the book are those that thrum with the postwar promise of a cleaner, brighter, future-forward Britain, with a capital to match. Anyone who has tried to navigate the concrete maze of the South Bank, for example, will have to double-take at the map produced for the 1951 Festival of Britain, with its clear flow of lines and arrows around the Royal Festival Hall to Rodney Pier and beyond.

The book itself is straightforwardly organised, grouping maps around the broad themes of demographic record, administrative organisation, city life, and imagined conceptions of the city. Under the combined pressures of commercial growth, sustained population increase, and an ever more complicated transport network, the pressing need to navigate the expanding city is clearly apparent as one of the key motors of London’s cartographic history.

The earliest surviving maps are genteel affairs; Martin Van Valkenborgh’s mid-16th century depiction shows elderly couples strolling past archers and fullers in Moorfields, with Shoreditch surrounded by windmills and the attractive planned gardens of wealthy citizens. Even by the end of that century, however, mapmakers’ attentions have shifted away from the fields to the bustling wharves of the city’s docks; the Thames, perhaps the most iconic component of any London map, was also to prove the city’s most vital artery in delivering the wealth of the nascent Empire to the city.

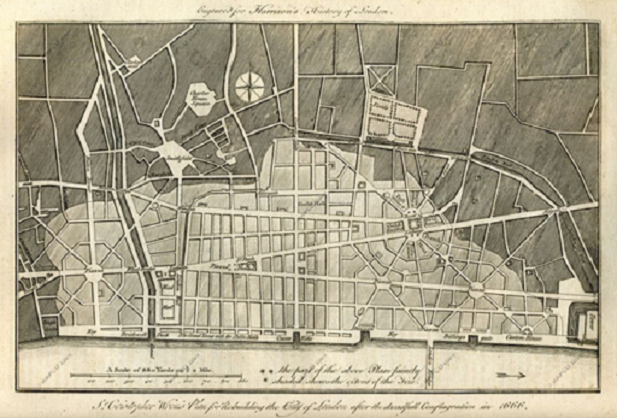

Another crucial moment in London’s history, the great fire of 1666, is vividly illuminated by the maps produced in its wake; John Oliver’s 1680 map, identical in all fundamental aspects to its modern equivalents, is a world away from the stylised sketches of a hundred years prior.

By the nineteenth century, London’s maps were not only organisationally comparable to contemporary examples, but also seem far more familiar in the territory they depict; west and central London appear almost indistinguishable from modern renditions, and the rapid sprawl south and eastwards, eating up Bow Green and Rotherhithe marshes, is well underway.

The industrial revolution was also affecting London’s mapmaking in other ways; with late-nineteenth advances in large-scale printing techniques, the city’s transport routes begin to take on the rich red, yellow and blue hues associated with contemporary OS maps.

It was the expansion of London in this period – sudden and explosive even in the context of the city’s prolonged history of near-constant growth – that saw new efforts to map land use, population distribution, and even the spread of disease, rather than simply to offer a navigational aid around the metropolis.

Here, the political contexts underlying the urge to map becomes ever more apparent, particularly when cartographers of different stripes plunged into the riotous social and infrastructural intricacies of London’s notorious slums. A 1901 map documenting ‘The Jew In London’ coloured whole swathes of the East End red, stoking antisemitic and anti-immigration feeling in an area of the city recurrently prone to racial tension; fifty years earlier, the epidemiologist William Farr had endured public ridicule for his attempts to arrest the ravages of cholera in London’s poorest districts by mapping its spread outward from water pumps.

Other cartographic efforts were more prosaic; the neat ecclesiastical boundaries depicted in 1877 remain a necessary, if reductive, starting point for tracing one’s way through centuries of intricate parish politics and ad hoc bureaucratic arrangements. Every inch of the city was being claimed, assessed, and valued; colour-coded maps for calculating for insurance premiums, for example, added yet another tonal lens through which the living city could be appraised.

Poring over nicely reproduced maps for their own sake will always be a pleasurable activity for those who are taken with that sort of thing; but Foxell’s book demonstrates the wider value of reading them more closely and contextually.

The range, and relentless rate of production, of top-down assessments of the city can be just as considerable as the more feted textual documentations made by its inhabitants. Moreover, an emphasis on the ways in which various cartographies are politically cast renders them a necessary companion to these personal approaches.

The importance of these emphases is discreetly but convincingly expanded upon in Foxell’s accompanying texts; such writing can be easy to overlook when placed beside all these (often very beautiful) maps, but here it is perfectly pitched – illustrative and supportive, while remaining aware that the visuals are doing all the hard work. With a handful of exceptions, the maps themselves are also reproduced from the source material with an impressive clarity.

‘Mapping London’ deserves an audience beyond the narrow world of cartographic history and antiquarian collectors; and it would be fascinating to see the kind of work Foxell does here applied to smaller conurbations, or to other great world-cities. So: take to the streets.

S. Foxell, Mapping London: Making Sense of the City (Black Dog Publishing, 2007, pp. 8-278, £24.95).

S. Foxell, Mapping London: Making Sense of the City (Black Dog Publishing, 2007, pp. 8-278, £24.95).

Andrew Fleming is a research student at St. Edmund Hall, Oxford, where he is writing a doctorate about the church in medieval England.

Leave a Reply