Jean Baudrillard: The Masses An A to Z of Theory

In Theory, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, October 26, 2012 0:00 - 0 Comments

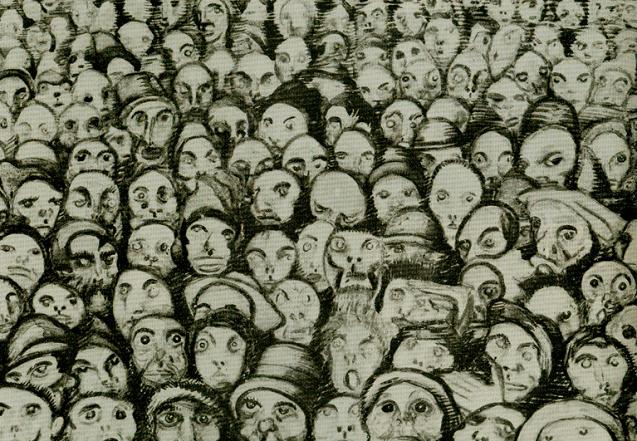

Josef Váchal’s Cry of the Masses (source: vachal.cz)

In discussing resistance from below, Baudrillard’s main emphasis is on the masses. The masses are the aggregate left in place by the operations of the code. They are a ‘homogeneous human and mental flux’. They are the ecstatic form of the social. More social than the social, they absorb the force of its other – inertia, resistance, silence. The masses are the product of the stockpiling of people by the system – whether in queues, factories, prisons or camps. They are the end-product of the social, but they also put an end to the social. They are the sphere in which the social implodes in simulation. People are seduced into the mass by a kind of ‘stupefied, hyperreal euphoria’ which arises from an experience of everything being on, and reduced to, the surface.

The masses are continuous with the proletariat in their desituated, atomised existence. They are people ‘freed’ from specific embedded positions, continuing to exist only as a statistical residue. They are no longer polarised or differentiated. Instead, they are dispersed like atoms. They are speechless – the ‘silent majority’. They do not express themselves. Instead they are surveyed and tested from outside. Hence they are within knowledge, but never represented. They are the product and counterpart of the code’s regime of testing and interrogation. They are created by simulation, not simply portrayed by it.

Despite their apparently abject position, the masses remain a powerful force of resistance. The only cultural practice left is the cultural practice of the masses. This practice is manipulative and depends on chance. It plays with signs, and has no meaning. It is based on an unconscious desire for the symbolic murder of the political class.

Baudrillard writes as if there is a constant strategic conflict, or invisible class war, between the system and the masses. This is not, however, a standard Marxist struggle in the superstructures. The masses are not oppressed and manipulated. They are not alienated. Rather, they are sovereign. They remain passive, and in this way, neutralise the system. Baudrillard insists, provocatively, that the masses are smarter than the critical theorists who denounce them as naïve or stupid. The critics make the mistake of thinking the masses believe in the things they take part in. The appearance of alienation is just a philosophical ideal applied to the masses for purposes of representation.

Instead of manipulation, there is a game between the masses and power (or the ruling class which retains ownership of truth), which both play through simulation. The rulers try to permeate society with meaning, while the masses struggle to neutralise or distort it. The idea of play or strategy involved here is anomalous and complex. Baudrillard sometimes treats the masses as a non-actor, an object; sometimes as a subject in struggle; and sometimes as acting unconsciously, without knowing it.

The masses aren’t mystified. It isn’t that they would aspire to reason, meaning or truth if only they knew. Instead, they know what they’re doing (at least unconsciously). They refuse meaning. They are a force of inertia which fails to conduct whatever passes through it. The masses have no truth of their own. They simply give a place to the effects of power. Hence, the demands on the masses to reveal their secret backfire. The masses do not have desires of their own, or a language of their own. They don’t even have ‘bad’, fascist or conformist desires. They reconstruct phenomena (such as politics and religion) in a way which strips them of the imperative of meaning. In doing so, they strike blows against power. In this way, the masses realise radicals’ goals by other means.

The masses obey the imperative to devour simulations. They are deterred. But for Baudrillard, they also unconsciously aim at annihilating the code. They try to do this by responding in the very terms used to appeal to them. They become ‘fascinated’, in an active, destructive way. This is a gesture of symbolic exchange. It returns the gift given by the code. The mass is also implosive through sheer numbers. There are simply too many people at events for instance – buildings aren’t strong enough, crowd crushes happen.

The masses respond to deterrence with disaffection or enigma, to tautology with ambivalence. They perform social myths, but don’t believe in them. They defeat the system through a massive withdrawal of the will. The masses refuse to know, will, or desire anything. They know they are powerless and ignorant, but they don’t want knowledge or power. It is as if the evil genie is telling them to refuse to make a choice, to leave it to advertisers to ‘persuade’ them. For instance, they withdraw into privacy, into a depoliticised everyday life. For most authors, the system imposes a rat-race on the masses. For Baudrillard, the masses convert use-value and need into a rat-race for status so as to sabotage objective economic management, rendering consumption unmanageable.

According to Baudrillard, the masses have always detested culture, and now participate enthusiastically in its mourning. They participate too enthusiastically, effacing the meaning which performances seek to restore, and threatening to cause the edifice to collapse. The masses are not produced as formless or uninformed by the media. They resist the media by absorbing its messages and returning nothing. The absence of a response when one is needed undermines the reproduction of power. Baudrillard criticises accounts which accuse the media of misrepresenting, saying there is nothing in common between simulation and meaning.

This portrayal may not be entirely accurate in discussing particular social strata, but expresses a particular social logic, or way of relating. Baudrillard recognises that audience research shows that the ‘masses’ actually produce their own, localised readings of media texts. He sees this as a universal ruse, directed against the power of modernity, which resists the fixing of meaning by the system. Yet it is also distinct from the practices of the masses. The masses, rather, function anonymously, redirecting meaning into the indeterminate sphere of fascination.

The system has to constantly expend energy to try to extract anything from the masses. Otherwise it is caught in inertia. Calls for social responsibility are usually ineffectual. According to Baudrillard, this is because people sense their alienated position and unconsciously resist political mobilisation for this reason. The demand or desire for meaning and the real dries up. The masses suck in meaning and destroy it. They offer a silence which cannot be represented or spoken for. The masses are a substance which resists – reminiscent of resistenz in historiography.

Baudrillard advocates the adoption of a stance as object. In contrast, alternative subjectivities, demands for voice, ‘consciousness raising’ and appeals to the unconscious involve a response as subjects to the system’s demand for an object-status, for submission. Baudrillard says there is a need for both, but the demand for subjectivity is now the greater part of the system, so the object-strategies are more strategically important. The position of the subject has become impossible to occupy. The only possible position, and strategy, is that of the object.

The reasons for this are psychological. Everyone invests something with object-status. Anything that becomes an object for another person is also a latent death threat to that person. These arguments of Baudrillard’s seem to stem from the Lacanian idea of the objet petit a. Baudrillard believes a particular kind of (probably fallacious) belief is actually necessary: the treatment of one object as the origin of the world. The object is crucial because it is not involved in the separation of things through meaning. An absolute object would be worthless and indifferent, and objective in excess. It would be so far from use-value as to exceed the category of the commodity.

The object seduces, whereas the subject desires. The problem with theories of desire is that they continue to privilege the subject. According to Baudrillard, desire is really a result of the desire to become, for the other, a seductive object or a pure event. Today the object triumphs over the subject. The object should be seen as driven by an ‘evil genie’ which resists subjugation. An object-like strategy turns the screen through which the event is refracted into a screen of disappearance. The masses might then seduce the media, rather than the reverse. The insurrection of the object is now the only one possible – but it is also inescapable. This revolution will be obscure and ironic, not dazzling and subjective.

The object triumphs when it negates the system’s power of illusion. Today, illusion is either total or it is dead. Baudrillard notes that, whereas people still say “it’s only a movie”, people don’t say “it’s only TV” (especially not of reality TV or CCTV footage). This is because we’re no longer in a universe of reference. The moment people can say “it’s only TV” or “it’s only information” would be the moment of social change. (Can one imagine a time when televised evidence is seen as unreliable?)

The adoption of an object-position makes a certain amount of sense. Neoliberalism, or precarity, is a situation which arguably gives greater choice than earlier forms of capitalism. However, it tends to function by giving all bad choices, then blaming people for their fate. It puts the field in which options arise beyond critique, and in this way, refuses political subjectivity entirely. To take an example, people from poor backgrounds might choose between dead-end jobs paying below reproduction costs and illicit economic activities which pit them against the growing repressive apparatuses. Either way, they don’t achieve neoliberal “success”. But either way, their “failure” can be blamed on “bad choices”. To someone in such a situation – unless they reconstruct a power to alter the frame which creates the choices available – the situation leads to fatalism. People feel they can’t control their lives or their destiny.

The masses seem to conform to a degree which is excessive over what the system wants, without the participation the system needs. This is a kind of overconformity, akin to a work-to-rule. Baudrillard treats overconformity as subversive, taking the system to excess and hence collapse. It is the resistance of an object which refuses to become the subject the system wishes it to be. Neoliberalism demands that we all become ‘active subjects’, participating in our own exploitation by aspiring to ‘excellence’ and ‘success’. It demands that we take part in producing meaning. Practices of acting like an object – dependence, passivity, idiocy, overconformity – defy this demand. They reflect meaning without absorbing it. One might ask however: Why wouldn’t overconformity simply lead to a more extreme version of the system?

According to Baudrillard, the uselessness of the masses leads to their triumph. The masses, and the hostage, take their revenge on power. They are not only nonexistent as subject. They are also inexchangeable as object. One doesn’t know how to get rid of them. The hostage is very difficult to turn into political or economic currency. (This is perhaps why negotiation becomes less frequent, why war becomes limitless). This leads to the collapse of the value (or identity) of the hostage.

The similarities and the differences between Baudrillard’s view of the masses and theories of resistenz and infrapolitics are noticeable. Like such theories, Baudrillard maintains that the masses put up an empty performance in public discourse, and effectively subvert it. Where he differs from such theories is in denying the existence of a second layer, a hidden transcript.

I suspect that Baudrillard exaggerates the unconscious emancipatory desire of the masses. It is true that the masses sometimes sabotage the system through sheer force of numbers. But it is also the case that many of them are easily manipulated into the kinds of fascistic resurrection of power Baudrillard elsewhere criticises. It is not always clear that the masses do resist or fail to absorb meaning and truth. In particular, the phenomenon of the tabloids is conspicuously absent from Baudrillard’s account.

In seeking to portray apparently depoliticising effects of resistance to politics, Baudrillard has to stretch his argument. His depiction is often contradictory. The masses are coextensive with terrorism, but care more about a football match than a political deportation. They are counterposed to radical agendas of progress and agency, yet actualise the radical project. They are a void, an effect of power, yet also have counterstrategies of their own. Sometimes, Baudrillard suggests that the masses are simply a concept, not identical with any particular population.

Perhaps the ‘radical’ mass are those who are so disaffected that they no longer even buy into this kind of regime propaganda – the non-voters, the overworked, people with an extractive view of the system, perhaps hedonists or retreatists or ritualists, perhaps the self-consciously amoral constituency of sites like 4chan. Perhaps Baudrillard is referring to something like the autonomist concept of exodus, where people withdraw their bodies, labour or psychological attachments from the system, becoming indifferent to it. Communes, drugs, religious cults are sometimes portrayed as forms of implosion of the social. Examples could be multiplied. Voter apathy, for instance, might be seen as a form of implosion.

But then the question arises of whether people are escaping the impact of ideological apparatuses to such an extent as to desire the system’s collapse. Most seem to have very conformist standards of “success”. And many get drawn into the reconstruction of meaning and the persistence of fantasies of a return to a strong order. Baudrillard leaves too little space in his theory for bigotry among the masses – perhaps because bigots are not truly ‘masses’, but reactive forces. The account of the masses is also complicated if the masses turn out to have local knowledges, local sites of alternative attachments and so on. And the segmenting of the masses into niche markets, yes/no classes and so on is absent from Baudrillard’s discussion of their political effect.

These issues can be resolved by reinterpreting Baudrillard’s theory in a particular way. It perhaps makes most sense to think of the ‘masses’ as a social logic or a subject-position that some people adopt and others don’t, or that people adopt to varying degrees. If interpreted this way, it is not descriptively identical with the population or with particular constituencies such as TV viewers. It consists of these constituencies to the extent that they adopt the passive, object-like status suggested by Baudrillard – but not to the extent that they adopt active or reactive stances instead. In one passage, Baudrillard suggests that the masses coexist in each of us with a voluntarist, intelligent being who hates the masses.

[Part Thirteen will be published next week. Click here for other essays in this series.]

Leave a Reply