This Is How You Find Yourself: Junot Diaz, Diasporic Narratives and Decolonising Literature Sister Outsider

New in Ceasefire, Sister Outsider - Posted on Wednesday, October 24, 2012 10:03 - 5 Comments

By Hana Riaz

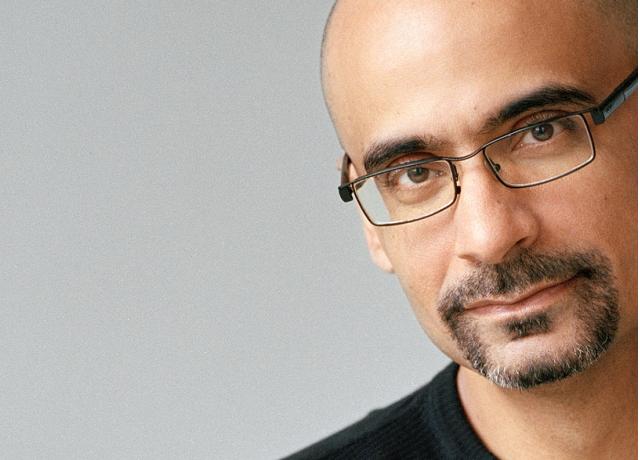

(Photo: Nina Subin)

It’s true and I won’t hide it: Roald Dahl was as far as I ever ventured with most white literature as a kid. Unlike my mother who was born and raised in a Pakistan still weighing heavy with the colonial imagination, rosy-cheeked white children and their adventures in the countryside did little to captivate me. Whilst these books built a world in which she could construct an ‘innocent’ Englishness (that she would only encounter in her late twenties), I was already in classrooms with children that had rosy-cheeks and mouths stuffed with racist slurs. In being unable to identify with these stories or the children that lived in them, I was silenced by my own absence and their totalising and pervasive presence; reading no longer offered a medium of escapism or the safe space of the imaginary.

Despite the fact that I was privileged enough to have a grandmother (a poet who knew six languages) teach me to read aged three or four, I was quick to give up reading fiction by the time I was eight. For the next ten years autobiographies and socio-political, historical accounts exploring Western hegemony, colonisation and resistance struggles dominated my bookshelves. It wasn’t until I began my undergraduate studies that I rediscovered what would become an undying and necessary love for creative writing and fiction. Here in this new world, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Jhumpa Lahiri, and Edwidge Danticat amongst many others were building a crucial post-colonial political project. Junot Diaz’s latest collection of short stories, This Is How You Lose Her, however, brought both this project and journey more recently into full perspective for me.

This Is How You Lose Her takes readers through what Diaz describes as the “rise and fall of a young cheater”; a journey centred on Yunior, a character familiar to devoted readers of his past works Drown and The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Like Diaz himself, Yunior is a Dominican-born immigrant raised in New Jersey attempting to reconcile love, loss and belonging over time. Sewn together by intimate first and second person narratives, Diaz’s literary brilliance shines through employing language in a way that is both crude and comedic, yet urgently and passionately tender.

Yunior remains exhaustingly lost as he navigates his father’s infidelity, his mother’s devotion, his brother’s tragic death and the women who make in and of these circumstances: begging, forgiving, creating and necessitating loves that are reflective of the cracks splitting beneath his seemingly shallow exterior. It is in between these spaces that readers are introduced to a realm of the deep unravelling of human connection that isn’t always as promising as it is brutally honest.

Whilst this collection of stories is hopelessly heart breaking, in uncovering the depths of how profoundly patriarchy, racism, imperialism and classism affect our personal experiences of love, Diaz’s work provides an alternative kind of solace for an immigrant and diasporic reader. Like his previous works, This Is How You Lose Her becomes an unrepentant safe space in which the reclamation of the black immigrant experience is defined not only by the stories told but more importantly how they are told.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s seminal series of essays, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature, produced in the 1980s, conceptualised the struggle for liberation by African peoples within the context of creative literature. At the heart of his call for self-determination was the role language had to play in the capacity for which people could and needed to define themselves – personally, politically and most importantly culturally. For him, the role of the English language was imperative in the institutionalisation of colonial power – a subjugation that was fundamentally spiritual as it was physical and as a consequence has aided contemporary neo-colonial domination.

Language, in carrying culture, defines “how people perceive themselves” and thus affects “how they look at their culture, at their politics and at the social production of wealth, at their entire relationship to nature and to other beings”. In imposing foreign languages, the suppression of how native languages were used – spoken and written – ultimately became deliberately devalued and engrained psychic conditions of low-status, humiliation, and alienation from one’s natural self and experience.

Ngũgĩ points to the moral significance of European and English literature that worked to reify this process both as part of the colonial and colonised imaginary. Not only was much of the literature emerging in the colonial periods racist, even that which spoke to humanist explorations was entrenched within European historical, cultural and moral sensibilities. For Ngũgĩ, language is therefore not simply a string of words but holds “suggestive power beyond the immediate and lexical meaning”. How then could a person of colour growing up in a colonial landscape identify or reflect on such literature without experiencing an alienation from their own personhood and cultural environment?

The rediscovery and renewal of using native languages posits a regenerative force that enables reconnection and human liberation even in the diasporic postcolonial experience. “Language as culture”, Ngũgĩ argues, “is the collective memory bank of a people’s experience in history”, rendering story telling a wholly political feat. In asking where we exist in the narratives that form creative literature, what we really call in to question is the ongoing politics of relevance and representation that remains definitive of other areas of people of colours’ lives.

Writing in Dominican Spanish slang and English, Diaz answers these questions in a fundamentally contemporary and authentic way. Unlike his debut, Drown, his latter works have been published without a glossary – something critics have attempted to problematise as ‘losing’ readers that are unable to ‘follow’ the Spanish that is key in dialogue, the weighty emotion his stories carry and the narratives they are woven into.

In using Spanish without an unapologetic translation, little is in fact lost and Diaz takes diasporic readers to a place where reading becomes a radical, political act. It is here, in between the Spanish and English that we are able to explore our hybrid identities born out of migration, diasporic settlement and the racialised spaces that shape these experiences on our own terms. Language becomes an open door and Diaz’s non-negotiable bi-lingual writing encourages readers on the margins to own their narratives and stories entirely through setting the agenda by which they are to be understood.

But just as this postcolonial project is, in many ways, a resistive one – aiding the process of cultural decolonisation – it too is one crucially defined by creating safe spaces. Language in this case then helps to challenge the alienation that Ngũgĩ speaks of and opens up literature to a diasporic body often still trying to conceptualise what exactly home means in the hostile (and white) West.

I may not be Dominican American, nor have I personally experienced the stories Diaz recalls in his work, but there were many moments that brought a familiar and easy comfort throughout this collection. “Your mother flares. Who in carajo do you think you’re talking to? Say hello, coño, to la profesora,” writes Diaz in Miss Lora. Instantly I was taken back to my childhood where Urdu and Hindi provided key moments of identification: my mother slipping in and out of Urdu and English as she’d call to my brothers and me; or later when my closest childhood friend and I would speak in Hindi and sing Bollywood songs publicly at our all-white school as an assertion of who and what we were; or the learning of a catalogue of swearwords to defend myself on the bus when white children would yell “fuck off Paki”.

These moments were indeed riddled with everyday emotion defined by race and culture; they were the building blocks of my hybridised and complex British Asian identity. Being multilingual became imperative in creating resistant and safe spaces as a Pakistani in Britain– something that Diaz allows his readers to reconnect with, to understand, and to most importantly unashamedly return to through his use of Dominican Spanish and English. As a consequence, an alternative type of imaginary is instituted, one that is subject to relevance and reflection whilst still leaving enough room to escape in the way literature facilitates.

Diaz continues to create necessary narratives that address the questions we must continue to answer. In a British landscape, it is the call for people of colour to produce work by and for us, to let down white audiences through these critical methods that essentially allow us to engage with our stories and narratives on our own terms. It is in fact a plea to continue to connect postcolonial and diasporic literature to a broader framework in which we set the agenda for our belonging in the cultural fabric of this nation where race, class, gender and imperialism remain key constructs of our experiences.

If we are to complete this decolonising project successfully or see the fruits of regeneration come into full effect, however, we must also appeal to the alienated imaginary of our children. At a time where they are reading less and are increasingly socialised by racist and orientalist material, we must generate more Young Adult and Children’s fiction that speaks to the core of their experiences and renders them relevant agents. For me, at twenty-three, This Is How You Lose Her is a reminder that the healing process radical reading initiates is in fact never too late and ‘home’ is closer than we think.

5 Comments

ashok

Eugene Egan

Thought provoking and reminds me of the excellent book by Edward Said ‘Culture and Imperialism’

Renuka

remember rushdie?

hana

thanks all. @renuka i personally never took to much rushdie, not a fan of his writing style. this wasn’t a denial of works already produced, just my own reflections on the reasons why Diaz’s latest collection of short stories really moved me.

[…] Read the full article on Ceasefire Magazine here Share this:ShareFacebookTwitterTumblrEmailPrintGoogle +1Like this:LikeBe the first to like this. artbelongingclassculturedecolonising the minddiasporaethnicityjunot diazlanguageLiteraturenarrativesngugi wa thiong'oPostcolonialracereadingspanishthe brief wonderous life of oscar waothe politics of african literaturethis is how you lose her ← Previous post Twitter Updates […]

excellent.