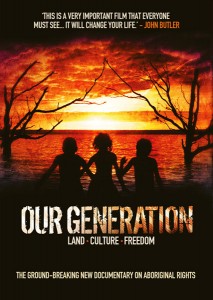

Film ‘Our Generation’

Film & TV, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Sunday, June 12, 2011 0:00 - 0 Comments

By Melanie Scagliarini

Attending the opening night for Our Generation was not the red carpet experience one may hope for at a film premiere; but then for a documentary about the persecution of Australia’s Aboriginal people, a glamorous outfit and a dozen photographers would hardly have been appropriate. Instead we were treated to a personal journey through the first people of Australia’s fight against racial discrimination, assimilation and genocide in this first world country known more for its sunshine, beaches and beer.

The stance is set from the moment the film gears-up: quotes taken from the UN’s latest report on the State of World’s Indigenous Peoples flash across the screen highlighting key terms. ‘Discrimination’, ‘dispossession’, ’extinction’ and ‘human rights violations’, all of which resonated with memories of newspaper reports covering the Stolen Generation and the government’s land-grabbing over the last few years.

Writing about this subject in the Guardian, the Australian journalist, John Pilger, stated that “the facts are not in dispute”. And with the use of many reports brimming with facts and figures coupled with an incredible depth of cooperation with the Aboriginal community, this film certainly sets out to prove each highlighted term one-by-one.

Spotlighting the Northern Territory’s Yolngu clan, we start in the present day with Elder Djanunbe giving us a tour of her home, “I live here at this house and I’m being a strong grandmother, but [I’m] living in a place that’s awkward with three families for themselves [in] only a three bedroom house”. The camera roams around the run-down property and shows a baby sprawled on a bed deep in slumber, various brothers and cousins asleep on the bed above and floor below. Another room with several put-me-up beds crammed next to each other and at least five people either dozing or sitting on them, and another room with more bunk beds and several mattresses on the floor. “We have to be overcrowded because there’s no more housing”, she explained. And there’s promises like housing is going to be built. Yet we are still waiting for those houses”.

Many of the aboriginal community are on welfare in homes provided for them by the government – often away from their traditional grounds, known as “the homelands”, from which they were often forcibly removed. Healthy food is expensive, as is medical care, and education is hard to come by. Taking account of all this, it’s perhaps unsurprising to hear that the rate of suicide within the Aboriginal population is more than triple that amongst that of non-indigenous descent.

Diseases, such as the easy-to-cure trachoma (commonly found in so-called third world countries and eradicated in all first world nations, except for Australia) are rife, and high rates of heart disease and diabetes contribute to an average life span of around 20 years less than their white counterparts.

Jostling back and forth through time the film shows stark footage of Aboriginal men in chains with the colony’s new inhabitants dressed in top hats and tails standing beside them; footage of young aboriginal women sweeping the floor outside the mission; and of young men being measured and weighed. The images conjure thoughts of America’s slave trade years ago; not Australia in the last century.

Speaking after the film, Director, Sinem Saban, explained why the film intersperses this black and white footage between modern day clips, “to understand the present situation of the indigenous population we need to learn the history”.

As a teacher in the Yolngu community, Saban’s prior friendship with the clan allows for an openness and directness from the interviewees that makes this documentary unique. It must surely be this trust that allows the film to confront the darkest of episodes that has occurred in recent times – the government’s infamous Northern Territory National Emergency Response to the allegations of child abuse within the area’s Aboriginal community.

Speaking to about this intervention former Indigenous Affairs Minister, Mal Borugh said, “We need to have control of those homes, the conditions that they are in, who is in them and what is occurring in those homes”.

This reaction to the Little Children Are Sacred report (the paper that outlined these allegations) was an unprecedented response that largely ignored the report’s 97 recommendations. What occurred instead were land-grabs, the halving of welfare, the closure of community ran centres and the implementation of non-indigenous leaders in place of Aboriginal leaders. A reaction which required a suspension of the racial discrimination act and which one of the authors of the report, Pat Anderson, deemed as “neither well-intentioned nor well-evidenced“.

Speaking after his tour of the tribal areas last year, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya, called the Australian government’s emergency response “racist” and considered its method one that “stigmatised already-stigmatised people”.

But, what about the children? Despite the government describing the situation as a national emergency, the film explains that out of 7433 aboriginal children who were subjected to mandatory sexual health exams, just four were thought to have been abused. As Elder Bob Randall, explained, “They ignored setting up rehab programs for children who have been abused. They didn’t even mention that. All they talked about was sending in the troops, sending in more public servants”.

But, what about the children? Despite the government describing the situation as a national emergency, the film explains that out of 7433 aboriginal children who were subjected to mandatory sexual health exams, just four were thought to have been abused. As Elder Bob Randall, explained, “They ignored setting up rehab programs for children who have been abused. They didn’t even mention that. All they talked about was sending in the troops, sending in more public servants”.

Despite decent housing, education and jobs cited as being key to combating child abuse in the Northern Territory, many Aboriginal people have claimed that there has been no real boost to these. In a perplexing turn of events, the government offered further housing in exchange for the transfer of the indigenous peoples land rights under a lease. The reason why? Many have suggested that the mining of uranium is a leading factor.

Whilst the film documents the heart-wrenching plight of the Australia’s indigenous population, there are one-or-two more positive moments in the film, such as former prime minister Paul

Rudd’s National Apology for the Stolen Generation – an act of assimilation that saw thousands of Aboriginal children taken away from their families.

With so many issues to cover there’s not a second wasted of this documentary’s 73 minutes. When asked about the breadth of coverage, Saban explained, “We wanted to give an overview of their situation… It’s definitely a film you need to watch more than once”.

Whilst it is a certainly a thoroughly accomplished piece, there is also a socio-revolutionary feel to it which lends to the film’s unashamed call to arms. This ‘people power’ has been further mitigated by the huge list of charitable organisations and philanthropists who have funded this film.

Heart-warmingly, with neither a distributor nor a marketing campaign it has mainly relied on word of mouth and is slowly burning through into the people’s psyche and gaining a reputation as ‘one to watch’.

For us watching it on the big screen, it certainly spurred a sense of social revolution within ourselves. After a moment of unprompted silence after the credits rolled, people of all ages and descent – British, Australian, African – stood up and asked “what can we do?”.

Rev. Dr. Djiniyini Gondarra, a Yolngu senior Elder who has featured heavily in this film, has travelled to London’s Australia House, where he campaigned on the central London building’s doorstep. He has since taken his mission to bring human rights to Aboriginal people to the highest order – the UN – to urge the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, to speak out once more against the intervention.

It seems little will stop this Elder ’s plan to fight the system. And with 2011 becoming the year of the revolution, if he and Sinem Saban have their way in transforming uninformed viewers into warriors fighting for the aboriginal peoples basic human rights, could the next revolt be in the unlikeliest of places: Australia?

Melanie Scagliarini is a freelance journalist and activist based in London.

Leave a Reply