Devil’s Advocate Where the Tea Party gets it right

Devil's Advocate, Features, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Thursday, October 14, 2010 18:55 - 1 Comment

By Omer Ali

By Omer Ali

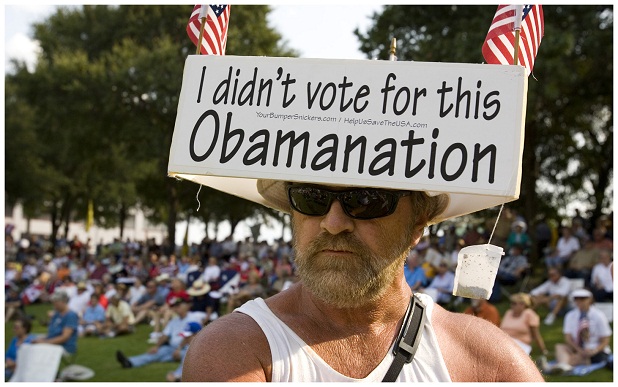

The modern Tea Party has been caricatured as a rabble of angry, white, middle-aged simpletons. Democrats regularly downplay its organic origins by emphasizing the overt support the movement receives from Fox News. It obviously doesn’t help that the channel, in the way it deals with the Party, displays a complete disregard for the line separating the reporting and the making of news.

In one instance, a rally organized by the channel was then covered in its news segment. The Party has been criticized for being vitriolic, reactionary, extremist and, at times, even racist. A closer look at the movement’s ‘philosophical’ underpinnings however reveals a different story. In this article, I will argue that, in fact, the Tea Party poses a fundamental intellectual challenge to the status quo in the United States.

‘Right’ and ‘left’ have long been used to loosely describe positions on the economic policy spectrum. ‘Right’ generally characterizes economic policies that are also described as ‘pro business’ or ‘laissez faire’. These general characterizations pose a problem because they come with heavy connotations – namely that ‘right’ not only describes preference for certain types of economic policies, but also pins down positions on completely unrelated issues. This is no doubt interesting, but for the purposes of this article, I will ignore the baggage these labels have and simply consider the economic policies with which they are associated.

Individuals identifying themselves as ‘leftist’ on economic policy are generally more tolerant of public involvement in the economy: they welcome regulation and think that the government is an important actor with a positive impact. This contrasts with the other side where individuals are generally more reluctant to see government involvement in the economy; they feel the government is inefficient and a necessary evil that should be minimized; they are opposed to taxes and even more opposed to regulation.

As with most issues bundled in ideology, it is not straightforward to determine whether government has a net benefit on society. The various effects of government on society are hard to disentangle, which makes the net effect unclear. In an attempt to answer this question, Clifford Whinston, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, surveys the academic literature evaluating the outcomes of government intervention in various markets. He finds that in most cases, government intervention either does not ameliorate the situation, or actually makes it worse.

That these results emanate from a Democratic Party bastion such as the Brookings Institution lends them credibility and importance. This is because the Democratic Party is generally considered to be on the left hand side of the spectrum and hence more open to regulation and government intervention. The author expressed astonishment at the consensus he gleaned from the literature.

The justification for government intervention in markets is for the government to address flaws in the working of markets that would otherwise yield a socially undesirable outcome – even les desirable than the hypothetical outcome of a well functioning market. The major sources of market failures so far identified comprise the following: the presence of externalities (both positive and negative), informational asymmetries between parties, the lack of competition, as well as the difficulty of starting operations.

An example of a market with positive externalities is education: acquiring an education not only benefits the recipient, but also benefits society through the skills acquired and deployed in the production process. The government in this case would be expected to subsidize education in order to encourage more people to seek it. The market for health care features informational issues that justify government intervention – the doctor typically knows more than the patient, which makes a case for government intervention that curbs the use doctors can make of this informational advantage.

An example of a market with positive externalities is education: acquiring an education not only benefits the recipient, but also benefits society through the skills acquired and deployed in the production process. The government in this case would be expected to subsidize education in order to encourage more people to seek it. The market for health care features informational issues that justify government intervention – the doctor typically knows more than the patient, which makes a case for government intervention that curbs the use doctors can make of this informational advantage.

A market that is dominated by a monopolist, or a few large firms, is one where competition between firms is not ferocious enough to tease out sufficient social benefits and hence government intervention in the form of antitrust law, or the competition commission takes place. For an example of the fourth case, consider any industry where the initial investment required to start trading is prohibitively high, electricity generation being a prime example.

Whinston’s findings are that, although most efforts were intentioned to be remedial, in fact, they exacerbated the situation; in some cases they altogether changed the targeted sphere of activity. That governments are argued to be inefficient does not have much explanatory power when the shortfalls of intervention are of this magnitude. What seems to play a significant role are first, that government structures, such as regulatory agencies, are subject to manipulation, and second, that they are incapable of carrying out their stated functions effectively. The failure of the Financial Services Authority in the UK and the Securities and Exchange Commission in the US to regulate the activities of investment banks is a case in point.

The first point was graphically illustrated by what came to light resulting the aftermath of the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. It emerged that the Mineral Management Service, a regulatory authority responsible for granting access to oil wells and maintaining safety and environmental standards was keeping close ties with oil companies who coveted this access. Unsurprisingly, the result was lax safety standards and a culture of graft. Indignation from both the public and the administration ensued; this resulted in a rebranding of the agency and some restructuring.

A fundamental question however was not asked: why should we expect things to be different this time round?

We shouldn’t. Indeed, whenever a government agency is responsible for distributing a scarce commodity amongst competing individuals or companies, rent seeking behaviour is to be expected.

To illustrate the second point, consider a case involving the UK’s Civil Aviation Authority, a regulatory body for the airline industry. One of its main duties is to certify the safety of aircrafts. Suppose a manufacturer has developed a new aircraft, the safety of which the Civil Aviation Authority needs to certify. Why should the Civil Aviation authority be better informed about the safety of this particular aircraft than the manufacturer itself? Indeed, it is not in the interest of a company to flirt with catastrophe.

The new technologies incorporated in the aircraft are the result of research happening within the firm; these results are kept secret for their value not to be diluted by spillovers to competitors. Latest developments are unlikely to be known by the regulatory authority.

Furthermore, a regulator is not needed at all in this case. There are companies competing in aircraft sales. These companies value their reputation since it affects profits through sales. They will then ensure that their aircrafts are safe since unsafe aircrafts are bad for business. The regulatory structure in this case is completely superfluous. All it does is that it gives companies yet another platform on which to compete.

Now however, instead of competing in the quality of the product or its price, there is competition in the standards the regulatory authority sets – resources are diverted towards of one set of regulations as opposed to another. This does however allow the government some control over the operations of private companies. Whether this is desirable or not is unclear.

Assuming that a regulatory authority does have access to information on technologies used by companies, that their operations are absent a profit motive will mean that they use this information less effectively in fulfilling their regulatory function.

Most types of regulation interfere with what companies in the market can do: they are restrictive. For existing companies, regulation is beneficial since it creates barriers to entering the market, fostering concentrated market power, which is one of the aforementioned sources of market failure. So by trying to address one market failure, the government invariably exacerbates another.

The irony is that leftists who encourage regulation claim the actual ‘pro-business’ ideology, in the new sense of the word meaning ‘beneficial for existing businesses’. Inadvertently, pro-regulation activities are pro-business, but only for existing ones.The bank bailouts program is but one example of government intervention benefitting existing companies.

The Tea Party’s three core values, fiscal responsibility, constitutionally limited government and free trade are reasonable enough. The Party’s formation comes hot on the heels of a gargantuan expansion in the federal government’s size. The health care bill and stimulus bills inflated the US government’s size to near one third of total GDP.

The Tea Party’s three core values, fiscal responsibility, constitutionally limited government and free trade are reasonable enough. The Party’s formation comes hot on the heels of a gargantuan expansion in the federal government’s size. The health care bill and stimulus bills inflated the US government’s size to near one third of total GDP.

The government services are not immune to the machinations of market actors. In addition, arguments in favour of limited government betray a concern for the self-interested behaviour of government agencies. For example, government agencies do not dissolve themselves when they are no longer relevent, instead they remain for as long as possible serving the interests of their employees rather than the citizen.

The image of government institutions as benign and neutral is persistent. Whenever a situation arises, a common comment is: ‘the government needs to do something about this’. In this way, the government is seen as competent and trustworthy. The Tea Party however espouses an alternative view, one that is suspicious of government. It treats the government as we have learnt to treat other actors in politics or the marketplace – to assume they are self-interested and that they act strategically. It is only when these characteristics of government institutions are taken into account that the effects of regulations can be better anticipated.

Omer Ali is an economist based at the University of Warwick and writes on economics, politics and world affairs. He is a former editor of the Voice Magazine. His “Devil’s Advocate” column appears every other Thursday.

1 Comment

Tom

A necessary article, finally some rational analysis of a much misunderstood movement. As you say, the roots of the Tea Party were organic and a rejection of wasteful government spending and repressive taxation. The original Tea Party movement was also strongly antiwar, lead by social libertarians like Ron Paul (true libertarians like him reject military spending on any projects but necessary self defence).

Then Fox News and a crowd of discredited, establishment fake conservatives like Sarah Palin essentially hijacked the show, diluted the demands and turned into a Republican advertising campaign, even though the original movement was strongly opposed to the neoconservative values that have subsumed that party and embroiled the U.S. in one foreign entanglement after another. Republican political figures were booed and hounded out of many of the early tea parties.

The tags of ‘right’ and ‘left’ should be discarded. As you say, they are misleading and have connotations which assist in the task of simplifying and distorting necessary debate (which Fox and Co. have stuck to with commendable tenacity).

I recommend watching some of Ron Paul’s speeches if you want to get a better idea of what true American libertarianism / conservatism stands for – he was the only candidate in the 2008 presidential election who had genuine grassroots support without the financial backing or the attention that comes with a corporate media-driven campaign like the one that catapulted the current President into office.

Ron Paul At The Arab American Institute Conference: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=98uqcdvv-98